The chemical element Promethium is one of the most challenging elements to study in the scientific community due to its high radioactivity and inherent instability.

The Chemical Element of the Nuclear Age

Promethium, with atomic number 61, exists in nature only in very small quantities. The Earth’s crust contains approximately half a kilogram of this element.

Researchers first discovered promethium by producing it in 1945 at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee as part of the plutonium enrichment program of the Manhattan Project. It is named after the Greek giant Prometheus, who stole fire and brought it to humanity, as nuclear energy is considered the second birth of controlled fire—or at least a similarly impactful invention for human civilization.

Promethium is an artificial element forged in the fires of the Manhattan Project.

Promethium, “the fire of the gods,” is an artificial element created in the fires of the Manhattan Project, the secret project aimed at developing the atomic bomb during World War II. After more than 70 years of remaining shrouded in darkness, promethium has gradually revealed its chemical properties and applications, opening new doors for science and technology.

However, the journey to explore promethium has been long and fraught with false starts. Before the official discovery of this element, scientists suspected the existence of an element with atomic number 61 due to gaps in the periodic table. In the early 1900s, several claims of discovery were made, but none could be substantiated with convincing evidence.

It wasn’t until 1945, at the peak of World War II and the Manhattan Project, that promethium was finally isolated. Researchers at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, led by Jacob A. Marinsky, Lawrence E. Glendenin, and Charles D. Coryell, identified promethium while analyzing byproducts of uranium fission in a nuclear reactor.

However, due to the project’s secretive nature, this discovery was not immediately published. It was only after the war ended that these findings were released, and the existence of promethium was officially confirmed.

After the war ended, the existence of promethium was officially confirmed.

The study of promethium’s chemical properties has faced many challenges due to its short-lived existence. Scientists had to employ the most advanced techniques of the time to gather sufficient data for their research.

Promethium is now regularly produced from the radioactive decay of uranium, although in very small amounts. Promethium can be used in simple compounds to produce luminescent paint or nuclear batteries. However, its high radioactivity renders promethium unstable. This instability complicates the formation of long-lasting compounds necessary for detailed research. Moreover, its crystal structure affects the chemical bonds of promethium, obscuring its fundamental chemical composition.

Alexander Ivanov and his colleagues at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory have now overcome these challenges. They have created aqueous promethium compounds. This method reduces some of the harmful effects of radioactivity and avoids the obscuring impacts of the crystal structure. As a result, for the first time, the research team was able to study the chemical properties of this element in detail.

Promethium can be used in simple compounds to produce luminescent paint or nuclear batteries.

Dr. Ilja Popovs, also from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, stated: “Because it has no stable isotopes, promethium is the last lanthanide element to be discovered and is the most challenging element to study.“

“There are thousands of publications on the chemical properties of lanthanides that do not include promethium, and that is a clear gap for the entire scientific field,” said Dr. Santa Jansone-Popova from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The Earth’s crust contains approximately half a kilogram of this element.

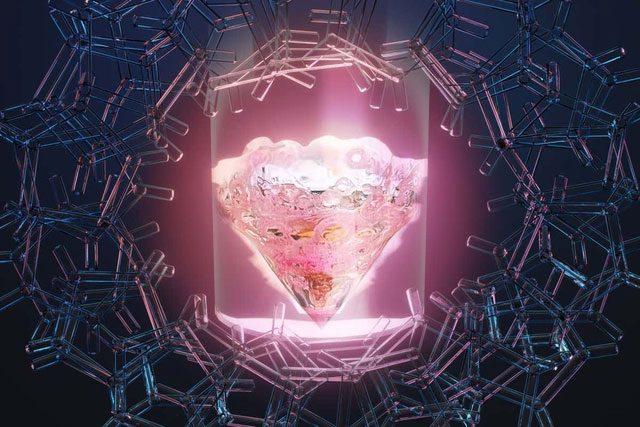

Breakthrough with PyDGA

Researchers synthesized a compound called bispyrrolidine diglycolamide (PyDGA), known to form stable compounds with elements similar to promethium. When promethium is introduced into the solution, it forms Pm-PyDGA, a compound with a bright pink color due to its electron structure.

To explore its chemical bonding, Ivanov and his team subsequently irradiated the compound with X-rays and measured the frequency it absorbed. This revealed how promethium is chemically bonded. The bond length between promethium and nearby oxygen atoms is approximately 1/4 nanometer, consistent with their computer simulations.

Andrea Sella at University College London told New Scientist: “It is quite a beautiful chemical reaction, and seeing the delicate pink of this complex is truly a joy.”

The unique properties of promethium compounds may provide a longer-lasting energy source.

Information about the bonding characteristics of promethium will help improve the process of producing purer samples in larger quantities from radioactive waste. This could lead to the design of new medical compounds, such as those used in radiographic imaging or cancer treatment. Ivanov stated: “This kind of fundamental information can help us drive new technologies.”

Furthermore, this research could influence the development of nuclear batteries and luminescent materials. The unique properties of promethium compounds may offer more efficient and longer-lasting sources of energy and light, which is crucial in remote or harsh environments where traditional energy sources fail to operate.

These findings were published in the journal Nature.