Thanks to underwater robots, researchers have discovered over 5,000 craters on the seabed off the coast of California that are not formed by leaking methane gas.

Off the Big Sur region of California, beneath the ocean surface, lies a multitude of large and small craters on layers of clay, mud, and sand. Decades after the discovery of these craters, scientists from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and Stanford University believe they have identified the cause of the series of intriguing circles on the ocean floor.

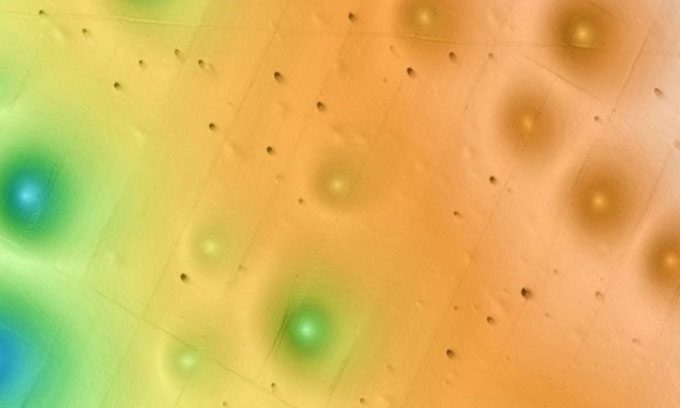

Map of the Sur Crater Field on the seabed. (Photo: MBARI).

According to a common hypothesis, the craters on the seabed are the result of methane gas or even hot fluids escaping from within the Earth, causing some fine sediments to wash away, leaving behind a crater. While this may be true for underwater craters in other parts of the world, the case of those on the California seabed is different, according to a study published in the journal Geophysical Research Earth Surface.

The Sur Crater Field off the coast of California is one of the largest in North America. This area is the size of Los Angeles and contains over 5,200 craters, with an average diameter of 175 meters and a depth of 5 meters. It is expected to be a potential offshore wind farm, but there are concerns that the presence of methane gas could affect the stability of the infrastructure.

During a recent expedition to the Sur Crater Field, which lies at a depth of 500 to 1,500 meters, an underwater robot operated by the MBARI research team found virtually no evidence of methane gas vents or other fluid flows. Instead, they suggested that the craters may have formed due to gravitational effects. The large craters located on the continental slope and the seabed samples collected by the robot reveal that sediments have been sliding down this steep slope for at least the past 280,000 years. The most recent slide occurred 14,000 years ago, possibly due to an earthquake or landslide.

Researchers at MBARI believe that such events could lead to erosion at the center of each crater. When a sufficiently large portion of sediment washes away, the erosion process causes the crater to expand further. This could explain why the craters appear in a chain-like formation.

“We collected a large amount of data, helping to uncover an unexpected connection between the craters and sediment flow due to gravity,” said technician Eve Lundsten at MBARI. “We could not initially determine how these craters formed, but with MBARI’s advanced technology, we have gained many new insights into why they have existed on the seabed for hundreds of thousands of years.” The Sur Crater Field is one of the most studied seabed areas in western North America.