Exploring the “hidden death” on the twin planet has significant implications for the future of Earth as well as the search for extraterrestrial life.

According to Science Alert, a research team led by planetary scientist Michael Chaffin from the University of Colorado Boulder has unraveled a crucial piece of the puzzle: Why is Venus – the planet often regarded as Earth’s most perfect counterpart – losing its water?

Venus also resides in the Goldilocks zone of the Solar System. Billions of years ago, this planet was once filled with water and had a temperate environment similar to Earth.

However, over time, it gradually dried up and became engulfed in a harsh greenhouse effect.

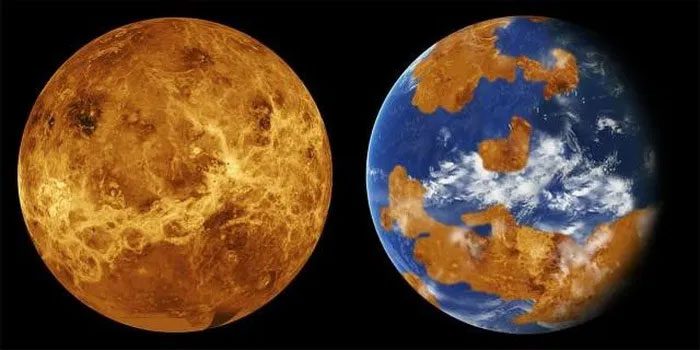

Current Venus (left) and its past – (Image: NASA).

“Venus currently has less water than Earth by a factor of 100,000, even though it is fundamentally the same size and mass,” said Dr. Chaffin.

The new study points to a process known as dissociative recombination, which causes Venus’s hydrogen to leak into space, as the potential culprit.

This involves the recombination of a molecule called HCO+, a positively charged ion made up of hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen, formed through the combination of carbon dioxide, water, and the loss of negatively charged electrons.

The research indicates that when electrons recombine with the molecule, hydrogen gas (H2) forms, which is quickly expelled from the compound into space.

Without hydrogen around, water can no longer form.

This mechanism may explain the dramatic loss of water in previous theories, neatly addressing the discrepancy between the water on Earth and that on Venus.

“There is a bit of a challenge. This model requires quite a lot of HCO+ in Venus’s atmosphere, which has not yet been detected on this planet,” Dr. Chaffin noted.

But this could be because we haven’t considered searching for it, so no Venus probes have targeted this molecule. This can be addressed in the design plans for future Venus missions.

According to the study published in the journal Nature, the unique chemical processes on Venus also highlight the fundamental differences that can make a planet habitable or deadly.

This illustrates how fortunate Earth has been in the past, as well as predicting the “uncertainties” that may arise in the future.

Additionally, the results show that the “death” HCO+ is something to be mindful of in the atmospheres of exoplanets.

So far, NASA’s instruments have discovered over 5,000 exoplanets, many located in the habitable zones of their parent stars, and similar in size to Earth.

However, scientists still need additional factors to filter more specifically for habitable planets, and HCO+ is a sign that a planet should be excluded.