According to researchers observing dog brain activity, these animals can understand many nouns referring to objects such as balls, slippers, leashes, and items commonly found in their lives.

New findings indicate that dogs’ brains can comprehend more than just command words like “sit” and “fetch”; they also grasp the meanings of nouns, at least concerning things they are interested in, as reported by The Guardian on March 22, citing research from Eötvös Loránd University in Hungary.

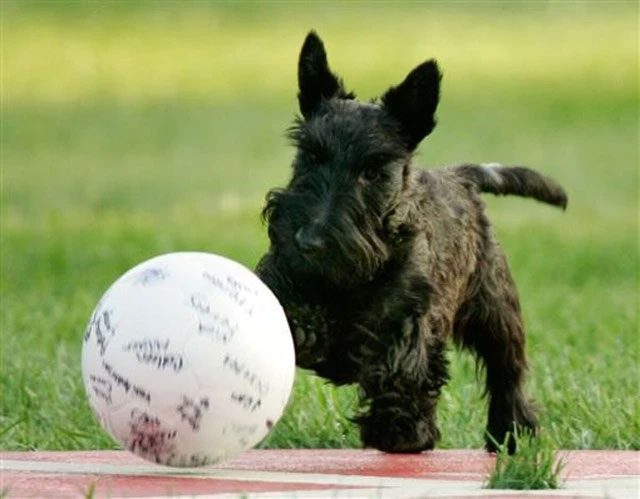

New research shows that dogs understand nouns for familiar objects. (Photo: REUTERS).

“I believe all dogs have this ability. It changes our understanding of language evolution and our thoughts on the unique characteristics of humans,” said expert Marianna Boros, who helped organize the experiments.

Scientists have long been interested in whether dogs can truly learn the meanings of words. A survey conducted in 2022 revealed that dog owners believe their pets can respond to between 15 and 215 words.

More direct evidence of dogs’ cognitive abilities was presented in 2011 when psychologists in South Carolina (USA) observed that after three years of intensive training, a Border Collie named Chaser learned the names of over 1,000 objects, including 800 fabric toys, 116 balls, and 26 plastic discs.

However, studies have provided very little information about what happens in dogs’ brains when they process words.

To learn more, Boros and her colleagues invited 18 dog owners to bring their pets to the laboratory along with five familiar objects. These included a ball, slippers, a plastic disc, a rubber toy, a leash, and other items.

The owners were instructed to say the names of the objects before showing their dog the correct item or another object. For example, the owner would say “look here, the ball is here,” while holding up the plastic disc.

The experiments were repeated multiple times, with the words able to accurately or inaccurately describe the objects, while the dogs’ brain activity was recorded.

The results showed that their brain activity differed between correct and incorrect descriptions. The most significant difference occurred when the owner spoke about the item the dog was most familiar with.

In the journal Current Biology, the authors of the study suggest that these results “provide the first neural evidence for vocabulary knowledge in animals.”