Scientists Never Imagined That the Blind Cave Salamander Would Leave Its Deep Cave. However, this unbelievable event has been recorded in streams in Italy.

The Blind Cave Salamander from Northern Italy has been observed leaving its underground home to embark on an expedition to the surface, according to the New York Times.

Breakthrough

Without eyes and with a spooky pale body after millions of years living underground, these blind cave salamanders seem to move back and forth on the sunlit surface using streams where the water bubbles from depths of several dozen meters.

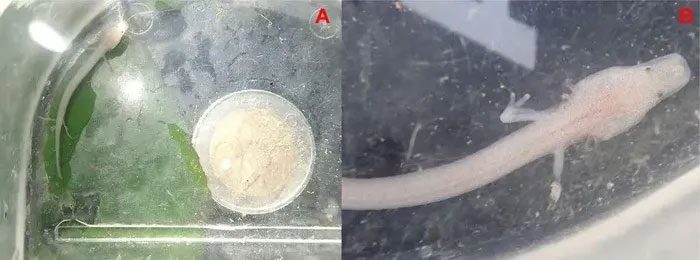

An adult salamander active during the day at a stream in Doberdò del Lago, Italy. (Photo: Matteo Riccardo Di Nicola).

Raoul Manenti, a zoology professor at the University of Milan (Italy), and his colleagues described this surprising discovery in a study published last month in the journal Ecology.

The Blind Cave Salamander, a species known as olm – the aquatic salamander – was once thought to be a dragon baby. While today we have determined that they will not grow wings, the aquatic salamander still bears a resemblance to mythical creatures.

Only as long as a banana, the aquatic salamander has an eel-like body and thin legs. Its face is unremarkable except for a frilled pink crown. When the aquatic salamander hatches, its eyes are quickly covered by skin, rendering it blind.

This creature navigates its dark world by sensing vibrations, chemicals in the water, and magnetic fields. They can live over a century and are known for their energy-saving abilities (one olm in the Balkans was recorded not moving for 7 years).

Over the centuries, some olm individuals have been found on the surface, but scientists believe they were victims of flooding. This creature has highly specialized parts for life underground, and researchers think they cannot survive outside their cave habitat.

To find an aquatic salamander, Dr. Manenti and his research team often had to descend into well-like water crevices to reach caves, including the Trebiciano Abyss, which is as deep as the height of the Eiffel Tower. However, in 2020, a group of explorers and ecologists, including Dr. Manenti, discovered an aquatic salamander swimming in a stream on the surface.

Image captured by a “camera trap” shows an aquatic salamander appearing on the surface in Italy. (Photo: Raoul Manenti).

Veronica Zampieri, then a graduate student at the University of Milan, began monitoring 69 surface streams in the area. She was amazed to find olms in 15 of those streams, even though there had been no recent floods. Some streams even regularly featured such aquatic salamanders.

Even more astonishing, Zampieri found olms swimming on the surface not only at night but also during the day. She noted that underground, the “bold olm” is an apex predator, but on the surface, its pale body and blind characteristics make it an easy target for predators.

What Are They Doing?

So what are these cave salamanders doing on the surface? Dr. Manenti employed various unique methods used deep in caves to uncover clues.

In population surveys, scientists quickly pulled olms from cave water to collect data. Dr. Manenti noted that sometimes an olm would accidentally swallow a bit of air during this process. Once returned to the surface, an air-swallowing olm would float on the water like a buoy and could not swim normally.

“At this point, we needed to make them burp,” Dr. Manenti explained. By gently “massaging” their long bellies, researchers resolved this issue.

However, in some cases, they did not just “burp” normally. The olms would sometimes expel “recent meals” that scientists identified as pieces of earthworms clearly not from deep within the cave. This indicates that the olms may have been hunting when surfacing.

Dr. Manenti suggested that it would be very energy-consuming for an aquatic salamander to maneuver up and down the stream, but the results seemed significant. While the aquatic salamanders are generally very slender, he and his research team found them unusually plump when surveyed on the surface.

Left: An aquatic salamander recorded in a stream at Sablici, near the A4 highway in the Monfalcone area (Italy). Right: The head and front legs of an aquatic salamander. (Photo: Raoul Manenti).

Danté Fenolio, an ecologist at the San Antonio Zoo who has studied cave-dwelling salamanders in North America for over three decades, stated that the discovery by the Italian team “challenges assumptions based on what has been recorded in North America.” He believes this could inspire further research on cave salamanders in the United States.

Zampieri remarked that the new discovery about aquatic salamanders highlights the ecological importance of places like streams, which connect two different worlds.

For Dr. Manenti, this connection was most evident one afternoon in 2022. Using a container from his lunch, he carefully scooped a tiny creature from the stream near the highway. It was the smallest olm ever discovered in the wild. Based on estimates from captive aquatic salamanders, this creature was likely only three months old in its life span of hundreds of years, indicating that olms not only travel to streams but may also reproduce there.

“The boundary between underground and surface is a human construct. Clearly, we have forgotten to ‘remind’ the olms,” Dr. Manenti humorously noted.