The human brain is exceptionally skilled at processing and responding to social signals, a vital skill for survival and social interaction.

Researchers have long been fascinated by how our brains can synchronize when exposed to similar experiences, especially lively ones such as movies or stories. This phenomenon, known as brain synchronization, is believed to play a significant role in how we connect, communicate, and empathize with others.

A study titled “Attachment Cues Activate Widespread Synchronization Across Multiple Brains”, recently published in the Journal of Neuroscience, has shed light on the neural foundations of human social relationships.

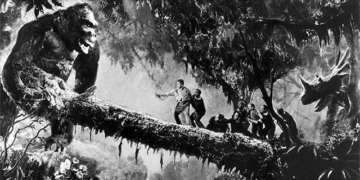

Our brains can synchronize when exposed to similar experiences. (Illustrative image).

Through this research, scientists discovered that observing daily interactions between mothers and their children can trigger similar brain activity patterns among different mothers.

This neural synchronization, particularly evident in contexts that showcase the closeness between mother and child, highlights the profound impact of such fundamental attachments on our brains.

The study involved a group of 35 postpartum mothers selected through online parenting forums. After a thorough screening process for suitability and mental health, 24 participants were chosen to take part in the research.

These mothers underwent two brain MRI sessions, during which they watched natural clips of mother-child interactions. The films included scenes of mothers they did not know holding their children. The scenarios varied widely, from “social” contexts where mothers and children were together, to “isolated” contexts where each character appeared individually.

The uniqueness of this study is further enhanced by its crossover design: before each scan, participants were administered oxytocin—a hormone associated with social bonding—or a placebo, in a randomized manner. When participants viewed the videos of mother-child interactions, certain brain regions exhibited synchronized activity across different individuals.

Notably, this synchronization occurred across a large portion of the brain, with approximately 44% of the examined regions responding to these bonding signals.

The synchronization was particularly pronounced in situations where mothers interacted with their children, as opposed to when they were shown alone. Key brain regions involved in this synchronization included those related to emotional processing and social cognition, such as the anterior cingulate cortex and the cerebellum.

Surprisingly, the use of oxytocin did not significantly alter the observed brain synchronization patterns. This suggests that the inherent bonding signals between mother and child are strong enough to trigger shared brain responses, independent of additional hormonal influences.

Furthermore, the study revealed an intriguing correlation between the observed behavioral synchronization—the coordinated interaction between mothers and infants in the videos—and the degree of brain synchronization among the viewers.

In other words, the more intimate and harmonious the mother-child interactions in the videos, the greater the synchronized brain activity among the participants.