The world described by NASA as a “second Earth” boasts a complex landscape with mountains, rivers, and lakes, reminiscent of our own planet, which has been reanalyzed.

A recent study published in the journal Astrobiology, led by astrobiologist Catherine Neish from Western University in Ontario, Canada, suggests that “the second Earth” Titan may not be habitable.

This conclusion starkly contrasts with what NASA has previously argued. The U.S. space agency considers Titan one of the primary targets in its search for extraterrestrial life, alongside other “life moons” such as Enceladus and Europa.

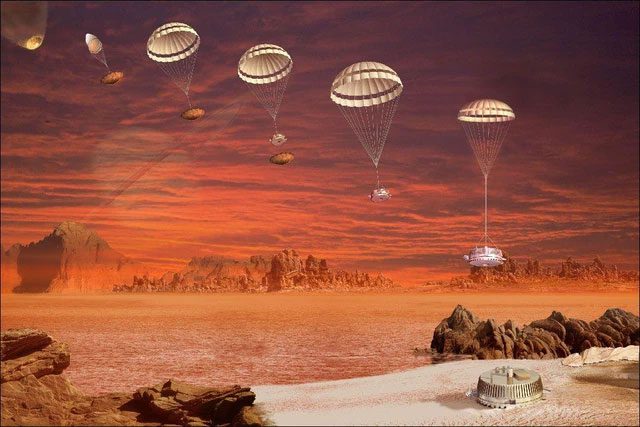

Graphic depiction of Titan’s landscape and the landing of the Huygens surface probe by the European Space Agency (ESA), in collaboration with NASA at the beginning of this century – (Image: ESA/NASA).

Titan, Enceladus, and Europa are moons of other planets in the Solar System. Titan and Enceladus orbit Saturn, while Europa orbits Jupiter.

All three show evidence of subsurface oceans that could harbor life. Additionally, Titan features an intriguing surface with the most Earth-like terrain, even though the “water” in its river and lake systems is actually liquid methane.

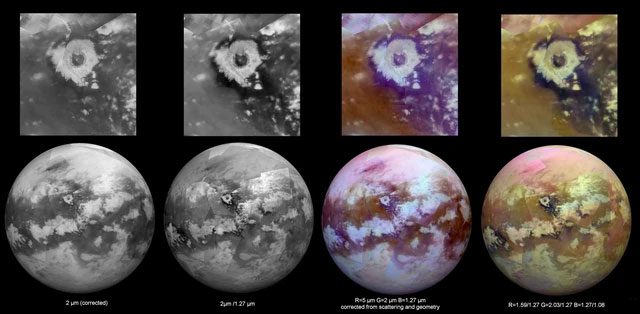

Color-enhanced image of Saturn’s moon Titan taken by NASA spacecraft – (Image: NASA).

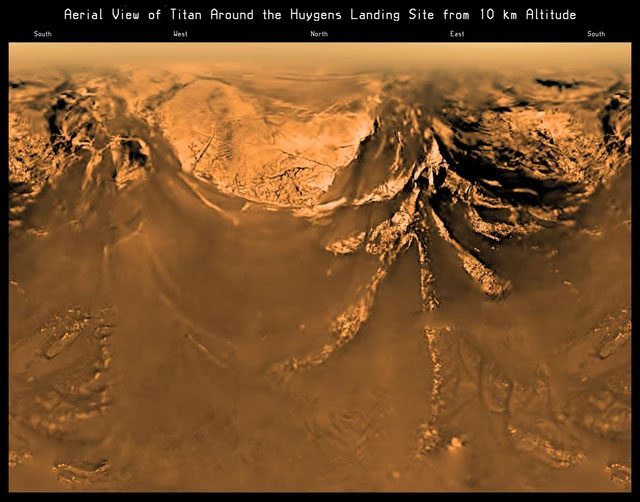

Another area of Titan with rugged mountains – (Image: NASA/ESA).

However, Titan’s subsurface oceans do contain real water, and possibly a lot of it, estimated to be 12 times the total volume of Earth’s oceans.

Titan also possesses organic materials confirmed on its surface.

According to Sci-News, in this new study, Professor Neish and her colleagues attempted to quantify the organic molecules that could transfer from Titan’s surface to its subsurface oceans, using data from impact craters.

Like Earth, Titan has been bombarded by comets and asteroids throughout its history, especially when it was “younger.” For a long time, the theory that these impacts simultaneously seeded organic materials has been supported.

However, unlike Earth, which has a surface suitable for life, Titan requires impacts to melt its icy surface, creating liquid water regions containing organic materials, which then gradually sink through the ice to reach the oceans.

Using hypothetical impact ratios on Titan’s surface, scientists estimated the nature and scale of the impacts, which helps predict the rate at which organic materials flow into the subsurface oceans.

In distant worlds like Titan, the surface is often too cold and harsh, making the subsurface oceans warmed by hydrothermal systems and tides the most suitable place for life to take root.

Results indicate that given the structure of this moon, the amount of organic material transported down is relatively small, not exceeding 7,500 kg/year of glycine, the simplest amino acid that constitutes life proteins.

The total weight of organic material, equivalent to that of a large elephant, introduced into a body of water with a volume 12 times that of Earth’s oceans is alarmingly minimal.

Thus, the ocean with such a diluted concentration of life materials would struggle to initiate the reactions necessary for life to emerge, as has occurred on Earth.

Surface of Titan’s desert region in a graphic featuring the Dragonfly spacecraft, which NASA plans to launch in 2027 for a Titan landing mission – (Image: NASA).

Of course, this study is just one of many arguments in the ongoing exploration of the fascinating world that NASA and ESA have “cared for” meticulously over the years. Many studies support Titan’s potential for life, while others contest it.

To find a definitive answer, we may have to wait for NASA, ESA, or other major space agencies around the world to conduct a direct life-search mission.