In 1936, Russian engineer Vladimir Lukyanov invented a unique mechanical computer that used water for calculations instead of gears and levers.

Early computers were mechanical devices made from gears and levers. These components could be moved with high precision and were connected to other parts to simulate the relationships between variables in mathematical equations. By moving a gear or pulling a lever, experts could change the variables and then observe the results in a different set of gears, with the new positions of these gears providing the answers they sought.

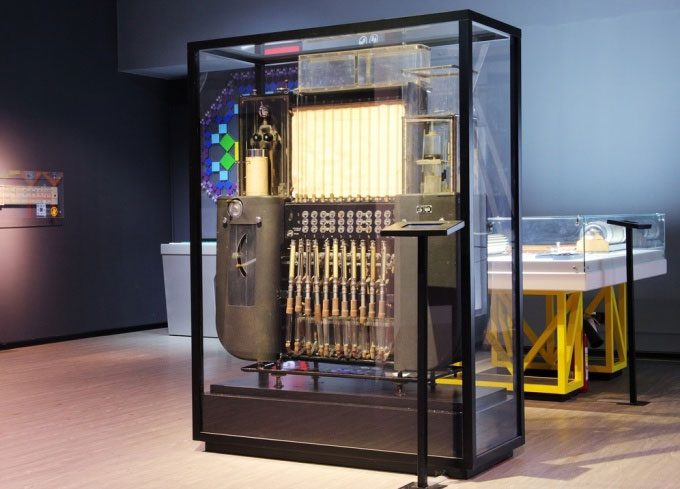

Vladimir Lukyanov’s water integrator. (Photo: kramola).

In the early 20th century, Russian engineer Vladimir Lukyanov created a special mechanical computer that did not use gears and levers but instead utilized water for calculations.

Lukyanov was one of the engineers involved in constructing the Troitsk-Orsk and Kartaly-Magnitnaya railway lines in the late 1920s. To ensure the quality and durability of reinforced concrete structures, the engineering team only poured concrete during the summer. Despite this, the concrete still developed cracks when temperatures fell below zero in winter.

Lukyanov believed that this issue could be avoided by carefully analyzing the temperature changes within the concrete mass, depending on the concrete’s composition, cement, technology, and external conditions. He began researching temperature conditions in concrete structures, but the calculation methods of that time could not provide quick and accurate solutions to complex differential equations concerning temperature.

While seeking a resolution, Lukyanov discovered that flowing water, in many respects, had similar patterns to the distribution of heat. He theorized that if he could build a computer primarily made of water, he could visualize the otherwise invisible thermal processes.

In 1936, Lukyanov created the prototype of the “water integrator” at the Institute of Road and Construction Research. At that time, it was the only computer capable of solving partial differential equations.

Lukyanov’s water integrator was an impressive system of pipes. The large machine, roughly the size of a wardrobe, comprised multiple pumps and interconnected tubes. The water levels in different compartments represented stored numbers, and the flow rates between them represented calculations. The results were displayed on a chart.

The early prototypes of the water integrator were made from corrugated iron, sheet metal, and glass tubes, and were designed solely for calculations in thermal engineering. Later models could address more complex problems, significantly increasing their applicability.

In the 1950s, a water integrator was developed with interchangeable parts that could be reconfigured in various ways, depending on the nature and complexity of the problem to be solved. The practicality of the water integrator grew to such an extent that these machines were mass-produced for use in laboratories and educational institutions throughout the Soviet Union. They were employed for a wide range of purposes, such as addressing construction issues on sandy terrains in Central Asia and permafrost layers, studying the temperatures of Antarctic ice sheets, and solving problems in rocket science.

Despite the emergence of electronic computers, Lukyanov’s water integrator continued to be used for a long time. It was not until the 1980s, with the development of compact, high-speed digital computers, that the water integrator began to become obsolete. Today, only two of Lukyanov’s water integrators are preserved in the Polytechnic Museum in Moscow, Russia.