Scientists have reported that the 3,500-year-old skeleton of an ancient Nubian woman could represent one of the earliest known cases of rheumatoid arthritis in the world.

The skeleton was discovered by archaeologists in 2018 during excavations at a cemetery along the Nile River near Aswan, southern Egypt. Analyses indicate that the woman was approximately 1.5 meters tall, aged between 25 and 30 at the time of death, living around 1750 to 1550 BCE. Researchers published their case study in the March issue of the International Journal of Paleobiology.

Due to the excellent preservation of the skeleton, which includes most bones, including the hands and feet, researchers were able to conduct a thorough bone analysis.

The skeleton of a woman over 3,500 years old. (Image: Getty Images).

The lead author of the study, Madeleine Mant, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Toronto in Canada, stated: “In many archaeological cases, you often do not have a complete skeleton. The well-preserved remains of this woman have given us the opportunity to examine this disorder that actively attacks the small bones in the hands and feet and talk about it a bit more safely.”

Analysis of the woman’s limbs suggests she may have had rheumatoid arthritis (RA), an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s tissues, leading to inflammation, particularly in the joints. Today, doctors diagnose this condition by combining imaging studies and blood tests to look for inflammation-related proteins and antibodies trained to attack the body’s tissues.

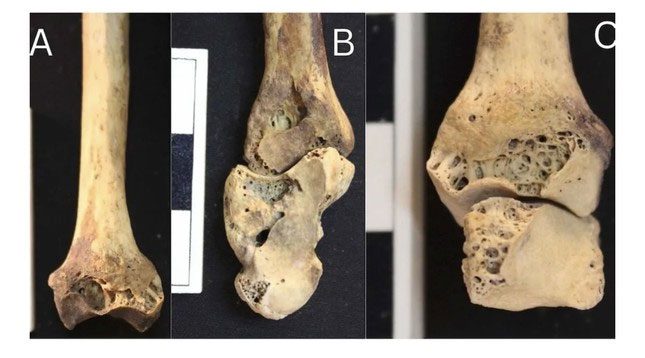

Co-author Mindy Pitre, an associate professor and chair of anthropology at St. Lawrence University in New York, USA, noted: “The joint surfaces themselves are not damaged, and in many other types of arthritis, you would see destruction where two bones meet. In this case, we found no destruction at the joint surfaces.”

Instead, researchers found “depressions or erosive lesions with smooth holes” in the woman’s bones, leading to the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, Pitre explained.

Pitre added: “I have seen osteoarthritis—that is one of the most common joint conditions we see archaeologically. It looks like bone against bone, like ivory. In rheumatoid arthritis, you do not understand that. The moment I realized, I noticed that the lesions looked abnormal.”

According to a 2023 study published in The Lancet Rheumatology, today, fewer than 1% of the adult population globally is diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. In contrast, it is estimated that nearly 8% of the global population suffers from osteoarthritis.

Pitre remarked: “It would not be surprising to say that, archaeologically, this is quite rare in ancient Egypt. Especially since people did not live long enough in the past to exhibit these kinds of lesions.”

The authors wrote in their new study that the earliest clinically described cases of rheumatoid arthritis did not even occur until thousands of years later in 17th-century Europe and did not mention this specific disease in ancient Egyptian texts. Other cases of RA in the archaeological record include 5,500-year-old bones from ancient Egypt and 5,000-year-old remains from Alabama.

Researchers stated: “It is difficult to know what impact RA had on daily life, but this woman likely experienced a reduced quality of life, especially as the condition progressed,” they wrote in the study. The body was found buried with grave goods, including a leather outfit decorated with beads made from ostrich eggshells and stones, a mother-of-pearl bracelet, and pieces of Nubian and Egyptian pottery.