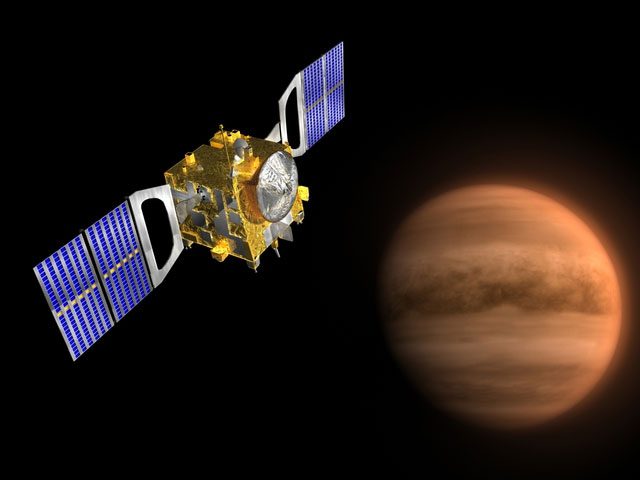

Venus is the second planet closest to the Sun, historically referred to as “the Bright Star” or “the Morning Star” because it is often one of the brightest celestial bodies visible in the early morning or evening sky.

Venus shares many similarities with Earth; its volume, mass, and density are comparable to those of Earth, earning it the title of “Earth’s twin.” However, the surface of Venus is a hellish world, with temperatures soaring into the hundreds of degrees Celsius, atmospheric pressure 90 times that of Earth, and an atmosphere filled with carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid vapor.

In such an environment, the existence of any life forms is considered impossible, and the survival of any artificial devices is extremely challenging. This planet captured the attention of Soviet space explorers.

From 1961 to 1984, the Soviet Union launched a total of 26 Venus probes, of which 18 successfully landed on the surface of Venus, setting many precedents for space exploration and providing valuable data and images to enhance humanity’s understanding of Venus.

The origins of the Soviet Venus program can be traced back to the late 1950s. At that time, Soviet space technology had achieved world-renowned milestones, such as launching the first artificial satellite, sending the first astronaut into space, and achieving the first space docking, among others.

Sergei Korolev, the leader of the Soviet space programs, believed that exploring other planets in the Solar System was a crucial objective of space exploration, and Venus was the most suitable choice due to its Earth-like characteristics and relative accessibility.

Korolev hoped to uncover the mysteries of this planet by understanding its origins, evolution, and potential living conditions, while also preparing for future human landings and colonization. To achieve these goals, the Soviet Union designed various types of probes with different functions, including spacecraft, orbital ships, atmospheric probes, and landers, as well as some hybrid probes, such as combinations of orbital and landing ships. These probes were collectively named the “Venus series” and numbered sequentially from 1 to 16.

Additionally, there were some probes that did not receive official designations, such as Venus 1VA and Universe 482, as well as some collaborative probes with other countries like the Vega Project and the Venus-Halley Detector.

On February 12, 1961, the Soviet Union launched the first Venus probe in human history, called “Venera 1.” This probe was initially intended to fly close to Venus to collect data about its atmosphere and magnetic field, but unfortunately, during its flight, communication with Earth was lost, and it could not complete its mission.

In the next three launches, only Venera 4 successfully traversed the dense clouds of Venus, entering its atmosphere and transmitting information about the atmospheric conditions of Venus. The Soviet Union then began developing a probe capable of withstanding the extreme pressure and harsh environmental conditions of Venus. The probe utilized a titanium shell with high-performance shock-absorbing equipment installed inside to prevent damage to its internal instruments in the event of an impact on Venus.

In 1970, the Soviet Union successfully launched the probe “Venera 7.” When the probe entered Venus’s atmosphere, it managed to descend to an altitude of about 60 km above the surface. However, due to the complex and unknown environment at that time, as well as technical limitations, the Soviet Union could not use engines to brake and slow down but could only rely on previously collected data about the dense atmosphere on Venus’s surface to determine the deceleration and land by parachute.

However, the extremely high impact speed upon entering the atmosphere caused the parachute to break six minutes later. Ultimately, the probe touched down on the surface of Venus at nearly 60 km/h and transmitted signals for just one second. This marked the first time humanity discovered the surface of Venus.

This second wave of data surprised scientists with the discovery that the air pressure on the surface of Venus is 90 times that of Earth, and the temperature reaches nearly 500 degrees Celsius, even higher than that of Mercury. Since then, the perception of Venus’s surface has shifted from being seen as “a beautiful goddess of love” to a fearsome hell.

The Soviet exploration plans did not stop there; on March 5, 1981, the Soviet Union launched the Venus 13 probe, which was an advanced spacecraft that had undergone multiple improvements and optimizations, consisting of an orbital ship and a lander.

Its mission was to conduct on-site research on the surface of Venus. After successfully passing through the dense atmosphere of Venus, it landed in the Phoebe region near the equator of Venus and captured a color photograph that shocked the world.

In the photograph, Venus’s surface appears as a yellow desert, attacked by sandstorms, devoid of any signs of life, evoking a terrifying hellish atmosphere. The probe also utilized soil drilling equipment to collect rock samples from Venus’s surface and conducted X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy analysis on them.

However, due to the extremely harsh environment on Venus’s surface, the probe could only operate under the high temperature and pressure conditions for two hours before losing contact with Earth. On June 7 of the same year, the Soviet Union launched the Venus 14 probe.

This probe was similar to Venus 13 but carried different scientific instruments. The lander survived on the surface of Venus for 57 minutes, during which time it transmitted back 8 photographs. One color photograph of Venus’s surface, along with some data about the atmosphere and surface conditions.

The images showed rocks, sand, and debris on the surface of Venus, as well as some structures resembling lava flows. The lander also analyzed Venus’s soil and collected information about its chemical composition and radioactive elements. The lander ultimately ceased operations due to battery depletion.

After a series of discoveries, humanity gained a deeper understanding of Venus and grew increasingly awed by this planet. The atmospheric pressure on Venus is sufficient to kill a person instantly, while the atmosphere contains over 95% carbon dioxide, creating a strong greenhouse effect that keeps Venus at temperatures soaring to nearly 500 degrees Celsius.

Additionally, there are large amounts of sulfuric acid vapor in the atmosphere, leading to frequent sulfuric acid rain falling on Venus’s surface. Such an environment can only be described as hellish and terrifying. Subsequently, two of the Soviet Venus exploration missions only conducted observations and mapping of Venus’s orbit without attempting any further landings.

The Soviet Venus project was an incredibly ambitious and grand space exploration plan, leaving a significant mark in space history and making a profound impression on humanity. It stands as a masterpiece of Soviet space endeavors and a pivotal milestone in the history of human space exploration.

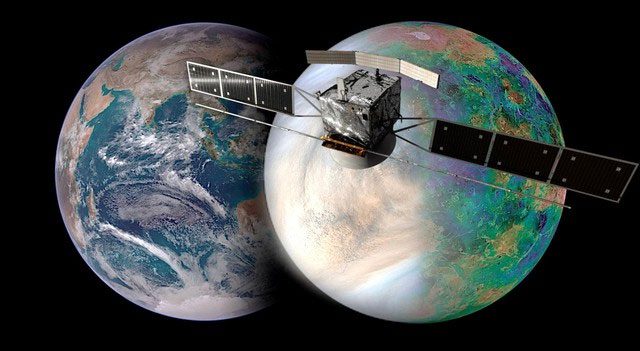

This marks humanity’s preliminary exploration of Venus and a profound understanding of the planet. Although the Soviet Venus project has concluded, human exploration of Venus has not ceased. With the growing interest and demand for Venus, along with advancements in technology and human equipment, the exploration of Venus will enter a new phase and level.