The ability to “multi-task” is essential in today’s life. However, doing two or three things at once is not always as effective as focusing on one task at a time.

In an article on The Conversation, Professor of Developmental Psychology at the Australian Catholic University, Peter Wilson, analyzes how our multi-tasking ability changes with age. This insight can help you practice and improve your own multi-tasking skills.

Doing multiple tasks at once is considered essential in today’s life. (Illustration: Verywell Mind).

According to Professor Wilson, we are all “time-poor,” which makes multi-tasking seem necessary in modern life.

We answer work emails while watching TV, create shopping lists during meetings, and listen to podcasts while washing the dishes. We strive to divide our attention countless times a day across both mundane and important tasks.

However, doing two or three things at once is not always as effective or safe as concentrating on one task at a time.

The dilemma with multi-tasking is that when tasks become complex or energy-consuming, such as driving while talking on the phone, our performance often declines in one or both “tasks.”

So how does our multi-tasking ability change as we age?

Doing More, but Less Effectively

The issue with performing multiple tasks at the brain level is that two tasks done simultaneously often “compete” for common neural pathways—much like two streams of traffic converging on a road.

Specifically, the brain’s planning centers in the prefrontal cortex (and its connections with the cerebellum and other systems) are necessary for both motor and cognitive tasks. The more tasks that rely on the same sensory system, such as vision, the greater the interference.

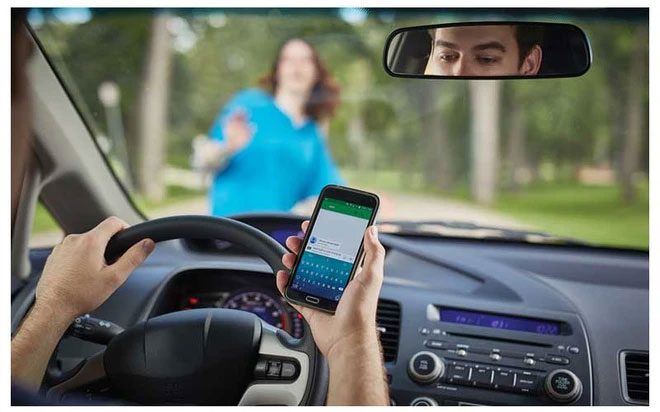

Using a phone while driving can be risky. (Source: Arrow Driving School)

This is why doing multiple tasks at once, such as talking on the phone while driving, can be dangerous. You will take longer to react to critical events, such as a sudden brake, and you are at a higher risk of missing important signals, such as traffic lights.

The more you talk on the phone, the greater the risk of an accident, even when using “hands-free” devices.

In general, the more proficient you are at a basic motor task, the better you can perform another task simultaneously.

For example, highly skilled surgeons can perform multiple tasks more effectively than interns, providing reassurance in a busy operating room.

High automation skills and efficient brain processes mean greater flexibility when performing multiple tasks.

Adults are Better at Multi-Tasking than Children

Cognitive capacity and experience provide adults with a higher multi-tasking ability than children.

You may notice that when you start thinking about a problem, you walk slower and sometimes stop if you’re lost in thought. The ability to walk and think simultaneously improves in childhood and adolescence, as does other forms of multi-tasking.

When children do these two activities at once, both their walking speed and agility decrease, especially when they are performing a memory task (like recalling a series of numbers), practicing fluent speech (like naming animals), or a precise motor task (like buttoning a shirt).

Furthermore, cognitive tasks may be sidelined as motor goals take precedence.

The maturation of the brain is closely related to this age difference. A larger prefrontal cortex helps share cognitive resources between tasks, meaning a better ability to maintain performance at or near single-task levels.

The white matter pathways connecting our two hemispheres (corpus callosum) also take a long time to mature, limiting the ability of children to walk and engage in manual tasks (like texting on a phone) at the same time.

For children or adults struggling with motor skills or coordination disorders, multi-tasking errors are more likely to occur. For them, even standing still while solving a visual task (like judging which of two lines is longer) can be challenging.

While walking, they take longer to complete a distance that involves cognitive effort along the way. You can imagine how difficult it is for them to walk to school.

What Happens as We Get Older?

Older adults are more prone to “multi-tasking” errors. For instance, adding another task while walking often causes older adults to walk much slower and with less agility compared to younger individuals.

This age difference is even more pronounced when navigating obstacles or uneven terrain.

Assessing multi-tasking ability can better inform clinicians about the future fall risk of older patients than merely evaluating walking, even among healthy individuals in the community.

Improving abilities can occur through activities like making shopping lists or playing word games while cycling for exercise. (Photo: AFP/TTXVN).

Simple assessments might involve asking someone to walk along a path while subtracting seven, carrying a cup and plate, or balancing a ball on a tray.

Then, patients can practice and improve their abilities in ways like composing poetry, creating shopping lists, or playing word games while cycling or walking on a treadmill.

The goal is for patients to be able to divide their attention more effectively between two tasks and ignore distractions, enhancing speed and balance.

Multi-Tasking Doesn’t Always Save Time and Energy

Don’t forget that good walking can clear our minds and foster creative thinking. Some studies suggest that walking can enhance our ability to search for and respond to visual events in the environment.

We often overlook the emotional and energy costs associated with multi-tasking when pressed for time. In many areas of life—family, work, and school—we think that multi-tasking will help save time and energy. But the reality can be different.

Doing multiple things at once can sometimes deplete our reserve energy and cause stress, increasing cortisol levels, especially when we are under time pressure. If multi-tasking is prolonged, it can leave you feeling fatigued or simply empty.

Deep thinking requires energy, and thus, caution is needed when acting simultaneously—such as being lost in thought while crossing a busy street, going down steep stairs, using power tools, or climbing a ladder.

So, choose the right moment to ask someone a challenging question—perhaps not when they are chopping vegetables with a sharp knife. Sometimes, it’s best to focus on one task at a time.