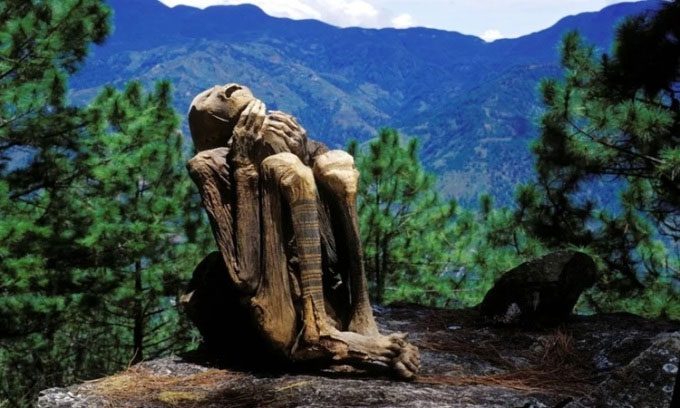

Dozens of fire mummies from 150 – 200 years ago in Kabayan may be destroyed by climate change and human impact.

Scattered throughout the Kabayan mountainous region in the Philippines are dozens of “fire mummies” that have remained intact for centuries. Known as meking by the local people, these well-preserved remains belong to the ancient ancestors of the indigenous Ibaloi people. However, environmental changes are now threatening to destroy these sacred mummies, as reported by IFL Science on January 24.

Many Kabayan mummies are covered in tattoos. (Photo: Alexis DUCLOS/Gamma-Rapho).

The term “fire mummy” originates from the preservation process of the bodies. Although the exact method of mummification has never been documented and is now lost, researchers believe that meking were smoked for an extended period, resulting in excellent preservation. The mummies were then placed in caves on the highest peaks of the Benguet region. At an altitude of nearly 3,000 meters, the cold mountain conditions help protect the bodies from degradation and decomposition, although climate change and human interference are causing some mummies to become infested with mold and insects.

In an effort to preserve the meking, a research team from the University of Melbourne installed environmental monitoring equipment in several caves containing the ancient mummies. This will allow scientists to track changes in humidity and temperature before deciding on the best measures to protect the mummies. While the research team hopes to safeguard the fire mummies in the future, other experts are still trying to piece together their history. Due to the secrecy surrounding the mummification process in Kabayan, which has only been passed down orally, this traditional practice lacks successors, resulting in many details being lost.

For instance, no one knows how many mummies exist or where the caves containing the remains are located. Researchers are also unclear about when and how the practice began, although local lore suggests that the first person to become a fire mummy was a chieftain named Apu Anno in the 12th century. Like many other fire mummies, Apu Anno’s body is preserved so well that his tattoos are still clearly visible. Stolen from his resting place in 1918, the chieftain’s mummy later paraded in Manila before being transferred to an antique shop and was eventually returned to the Ibaloi people in 1999.

However, Apu Anno’s mummy now contains a wealth of fungal spores and is located in a cave that the community cannot access. Recently, researchers were unable to accurately date Apu Anno’s mummy, although carbon dating tests on other fire mummies suggest they date back 150 – 200 years.

Scientists speculate that the bodies were tied to a fixture known as a “death chair” while being cleaned with saltwater and dried with smoke rising from burning herbs. No one knows for sure which plants were used by ancient people, though some older locals have shared various materials, including a local plant called Embelia philippinensis, chosen carefully for its antibacterial properties.