Charles Byrne lay in his hospital bed on a June day in 1783, without parents, without relatives, and not a penny to his name. Surrounding him were only his fellow performers in the circus.

A little person approached the head of the bed. He had to stand on tiptoe to hear Byrne’s last wish: “You must bury my body at the bottom of the sea, so I will no longer be brought out as a spectacle for anyone’s amusement.”

As the 7-foot-7 Irish giant whispered his final words, the others in the room—a bearded lady, a sword swallower, and an old fire blower—exchanged glances and bowed their heads, knowing that no one could help.

Byrne dedicated his entire youth to the circus. With his enormous, clumsy physique, the boy from rural Ireland could only make a living by displaying himself, entertaining the English townsfolk as a freak of nature.

From the muddy paths of Northern Ireland to the cobblestone streets of London, people would see the towering Byrne bowing to the elderly, handing balloons to children, and responding to every curious gaze with a friendly smile.

There was only one gaze that Byrne despised. It was the greedy look from the aristocrats who liked to collect.

They craved Byrne’s body as if it were a specimen—a specimen that would surely adorn the basement beneath their parlors. So much so that one collector approached his hospital bed and said, “Byrne, I want to buy your body after you die. Just give me a number and an address where my money can be sent.“

When the offer was rejected, the collector stood up straight, kicked the door in anger, adjusted his waistcoat, and threw a scornful glance before merging into the crowd surrounding apartment number 21 on Cockspur Street.

The local newspaper that year described these collectors as butchers ready to throw spears at a giant beast that was weary and worn out. These aristocrats were not shy about their ambitions, trying every means to obtain Byrne’s body, even resorting to theft.

Byrne: The Giant from Ireland

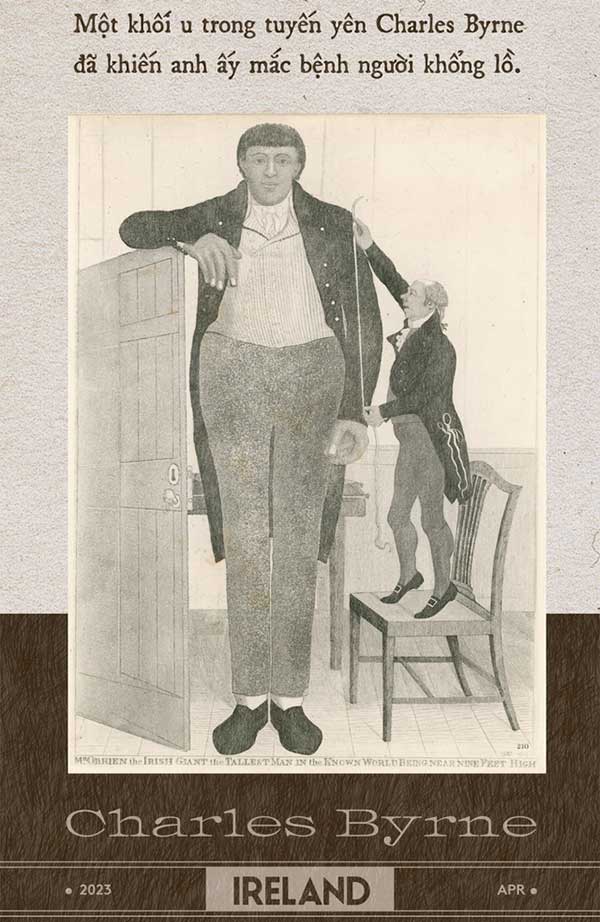

Charles Byrne’s real name was Charles O’Brien, born in 1761 in Littlebridge, a village in Northern Ireland. There are very few records about Byrne’s family. It is known that his father was Scottish and his mother a textile weaver. Both were healthy, of normal size, and not overly large.

Legend has it that Byrne was conceived on a sacred heap of hay. The villagers believed this cursed him to become a giant. At that time, it wasn’t known that the condition actually stemmed from a tumor in his brain.

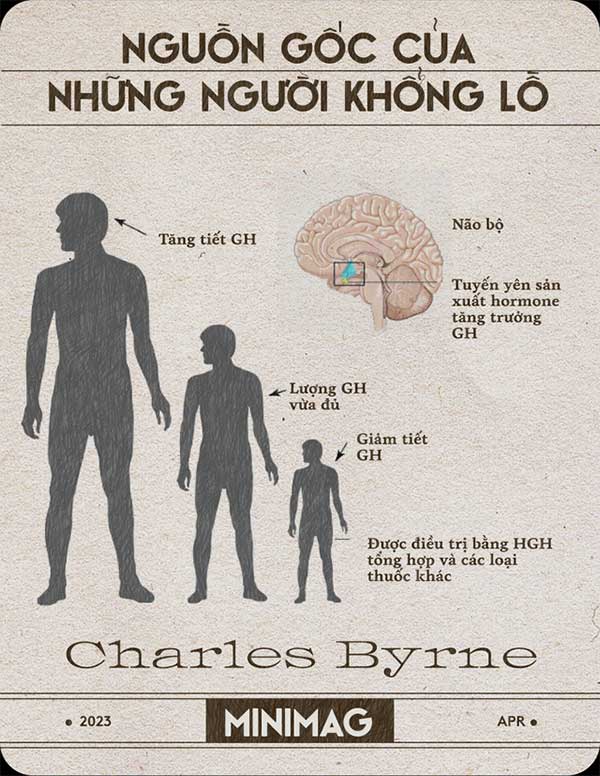

People with gigantism often have a tumor affecting the pituitary gland—a small endocrine gland located at the base of the skull. For Byrne, the tumor caused him to produce excessive growth hormone (GH).

Under normal conditions, GH is secreted in bursts 4 to 11 times a day. It stimulates the process of cell division in cartilage and bones. GH is what helps us grow taller and develop physically during puberty.

However, too much GH can cause problems.

Byrne was essentially unable to control his growth. As the growth plates at the ends of his bones remained open, GH continuously elongated his bones. As a result, even in his teenage years, he reached a height of over 2 meters.

When the growth plates eventually closed, GH caused Byrne’s body to expand horizontally. His forehead jutted out, his chin protruded, and his jaw expanded, leading to gaps between his teeth. If the tumor continued to compress the pituitary gland, Byrne could experience headaches, increased sweating, and impaired vision.

Thus, becoming a giant was more of a curse than a blessing. It caused the patient’s muscles to weaken, led to skeletal deformities, and significantly decreased lifespan due to obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other metabolic disorders.

Despite this, all giants like Byrne found in their teenage years a magical window where their superior physiques offered them more opportunities than their peers.

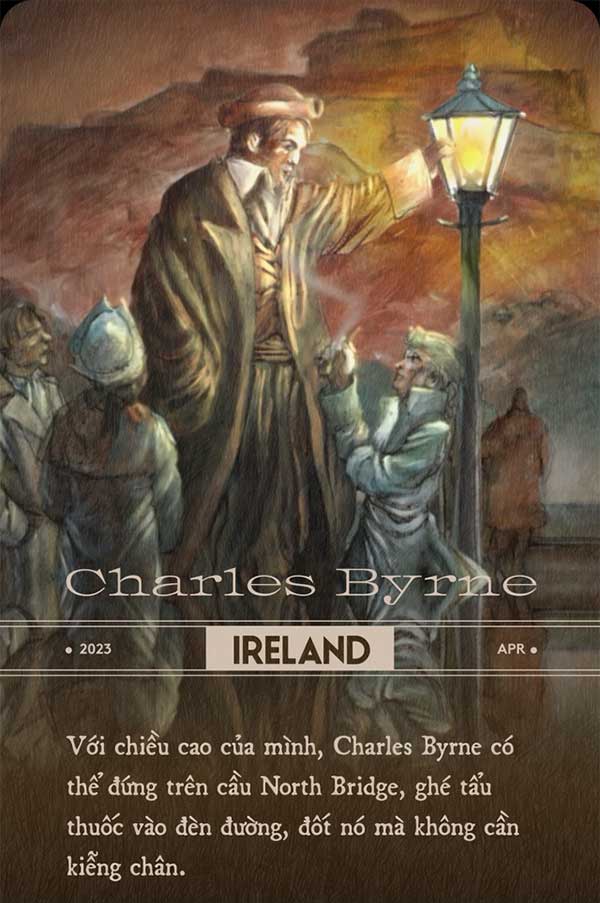

Byrne seized the opportunity to change his life during a runaway trip to Scotland. There, he had the chance to terrify the night watchmen in Edinburgh when they saw a giant standing on the North Bridge, puffing on a pipe against a street lamp, lighting it without needing to stand on tiptoe.

The sight of a wandering giant in the city caught the attention of all of Edinburgh, including the owner of a circus named Joe Vance.

In the 18th century, “freak shows” were becoming popular in the United Kingdom. They would gather dozens of people with unusual physiques to perform.

There would be little people, amputees, or those with small heads. Alongside them were bearded women, conjoined twins, and even individuals with two sets of genitalia. All of them were displayed as “freaks of nature.”

“Freak shows” attracted audiences from the lower classes to the aristocracy. The more unusual people a circus had, the more in demand it was. Some famous oddities even had the opportunity to perform for the royal family.

At a height of 7 feet 7 inches, Byrne now stood out from the crowd as a quintessential giant. The circus owner in Edinburgh realized that if he stood Byrne next to his previous giant, Byrne would tower over him by a head.

Thus, Byrne was immediately recruited. While the young man from rural Ireland was unsure of what other work he could find in the city, he nodded in agreement.

From Sought-After to Prey

Joining the Edinburgh circus, Byrne’s name gradually became known to many. He and his colleagues toured throughout the United Kingdom before stopping in London in early 1782.

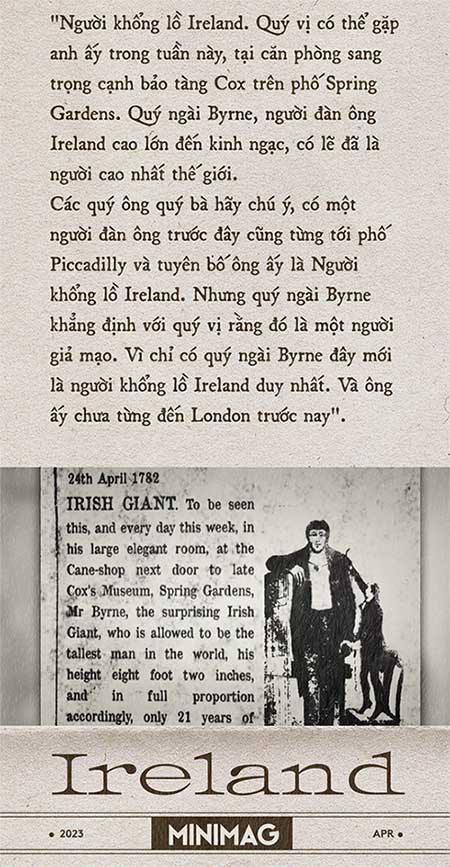

By this time, Byrne was so famous that his advertisements could dominate the newspapers:

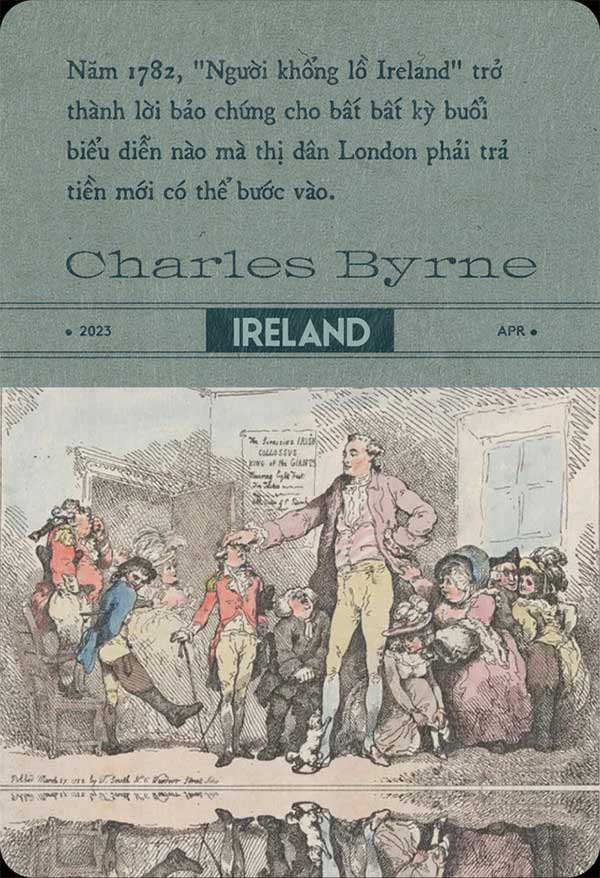

With sold-out performances, Byrne consistently filled theaters and shows throughout central London, from Spring Gardens to Piccadilly Street to Charing Cross. The presence of the Irish giant guaranteed any performance that visitors had to pay to enter.

The press and local people adored him, describing the giant as “gentle, friendly, and inspiring to the public.” A playwright even wrote a play for Byrne, Harlequin Teague (or The Giant’s Path).

But it was also at this time that Byrne began to attract the attention of anatomists and collectors in London, including John Hunter, who had an entire basement filled with bizarre biological specimens.

This is where Hunter stored over 14,000 specimens of 500 different species of plants and animals. He also collected human remains of unusual individuals. Hunter’s goal was to turn his collection into the most unique biological museum in the world.

With his ambition, he coveted Byrne as a living specimen. Hunter did not hide his intention to purchase Byrne’s body after he died, even approaching him with an offer of 130 pounds.

This was not a trivial sum, but the thought that after he died, people would strip the flesh from his bones, leaving only his skeleton to be placed in a glass case, terrified Byrne. He began to be haunted by the eyes with which Hunter and the collectors looked at him.

In 1783, Byrne’s health deteriorated. This was a result of gigantism, combined with an episode of depression. Dame Hilary Mantel, the author who wrote a novel about Byrne’s life, shared: “Although famous and at the peak of his fame, I know he was a tormented soul.“

Byrne may have been tormented by the meaning of his life. Despite his fame bringing opportunities to meet and mingle with many wealthy individuals, including King George III, Byrne still felt he was just a “gentleman” crafted by a freak show.

For Hunter, he was merely a hunted beast. This thought haunted Byrne even in his sleep. The pain from his giantism added fuel to the fire, driving him to seek solace in alcohol.

His despondency and illness led to a decline in Byrne’s performances. Londoners no longer flocked to the bustling streets to catch a glimpse of him; instead, anyone interested could find him at the Black Horse pub, perpetually inebriated.

The final straw came one day at the Black Horse when some petty thief took advantage of the Irish Giant’s drunkenness to steal two checks from his coat pocket. Those two checks contained all the wealth Byrne had accumulated during his touring days.

The amount was £770, equivalent to £160,000 today—an amount that many of Byrne’s contemporaries would spend a lifetime trying to earn.

Having lost everything, Byrne’s health deteriorated further. Everything led us back to the initial scene where he lay dying in an apartment on Cockspur Street. Outside, Hunter and a host of body collectors were lying in wait.

A local newspaper described the scene:

“This tribe of surgeons laid claim to the unfortunate Irish Giant who had just passed. They surrounded his house like Greenland fishermen preparing to harpoon a great whale.”

“One of them was so outrageous that he hid in his coffin, ready to pounce [and steal the corpse] at the moment the witching hour struck, when the church sextons had grown drowsy.”

The Most Controversial Body Snatching in British History

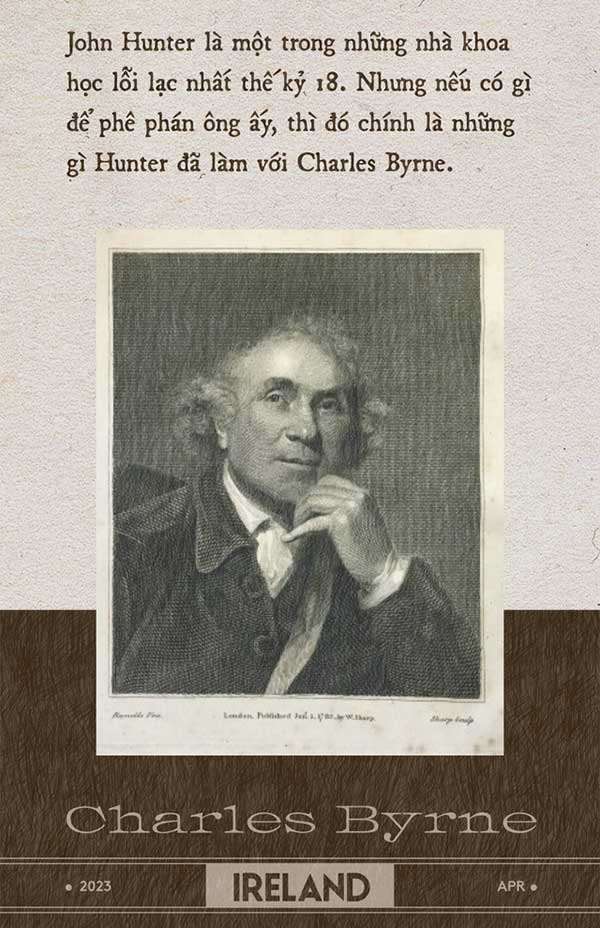

John Hunter was a Scottish surgeon, one of the most distinguished scientists of the 18th century. He was the mentor of Edward Jenner, the pioneer who invented the smallpox vaccine. Hunter himself performed the first artificial insemination in world history in 1790.

Through his work, Hunter contributed to the medical field with insights into growth, bone regeneration, inflammatory processes, gunshot wound treatments, sexually transmitted diseases, digestion, lactation, child development, the distinction between maternal and fetal blood supply, and the role of the lymphatic system…

However, if there is anything to criticize about John Hunter’s life, it is what he did with Charles Byrne.

This confrontation itself was an extremely disproportionate comparison. A small man beside a giant, a distinguished surgeon facing a circus performer, a wealthy, intelligent nobleman against a dying man who had lost everything.

When Hunter sought to steal Byrne’s body, it seemed no force could stop him.

***

Returning to Byrne’s funeral. To fulfill his wish, friends organized a fundraiser on the street to gather enough money for a lead coffin. They planned to seal Byrne’s body inside, transport him to the coastal town of Margate, and then hire a boat to cast the coffin into an unknown offshore location.

But somehow, Hunter learned of the plan. He hired a grave robber for £500. This thief formed a secret group to follow the funeral procession. When they stopped for the night at an inn on the way to Margate, the thieves took advantage of the group’s drunkenness to swap Byrne’s body with heavy stones.

The Irish Giant was brought back to London, where Hunter hid his body in his basement. Hunter spent several days dissecting Byrne, stripping flesh from him and boiling his bones white. He then posed the skeleton upright using joints and placed it in a glass case, admiring it privately for five years without revealing it to the public.

Documents indicate that Hunter feared public criticism. He was even afraid that if others learned of its existence, his valuable skeleton would be stolen.

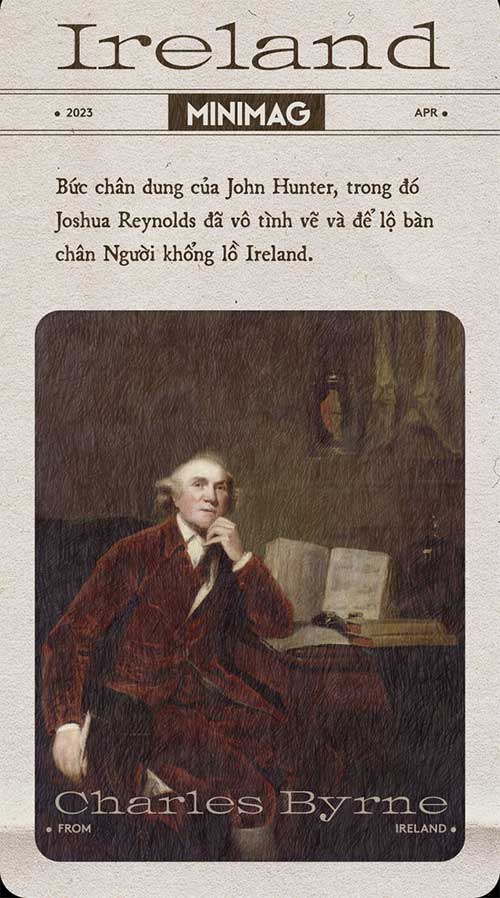

Unfortunately, during one session where Hunter commissioned a portrait from an artist named Sir Joshua Reynolds, Reynolds unknowingly included the massive foot bones in the background, not realizing they belonged to the famous Irish Giant who once roamed Piccadilly.

As more people began to learn of Byrne’s skeleton, Hunter felt something was amiss. What he once considered a terrible sin was overshadowed by public curiosity and his own growing notoriety.

No one criticized Hunter for stealing Byrne’s body; after all, the Irish Giant could be replaced by another. There was no shortage of individuals on the island who had excess growth hormone and could become giants.

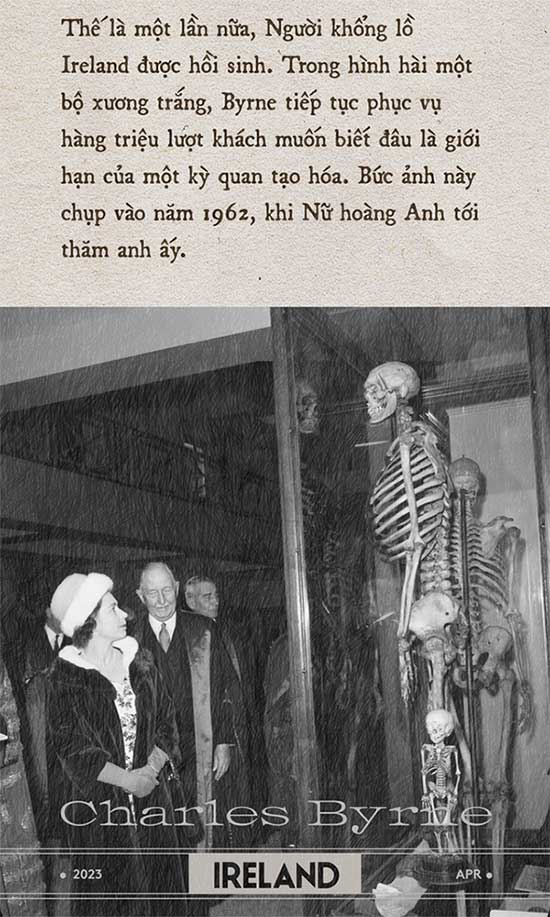

Feeling secure, in 1788, Hunter officially opened his collection to the public. Among it, Byrne’s skeleton was always displayed in the most prominent position. Hunter was now very proud of his most valuable specimen.

Thus, once again, the Irish Giant was revived. In the form of a white skeleton, Byrne continued to serve millions of visitors to Hunter’s museum, eager to understand the limits and wonders of creation.

Only, the Irish Giant no longer appeared friendly. He could no longer bow to the Queen, could not hand balloons to children, and could not see anyone anymore.

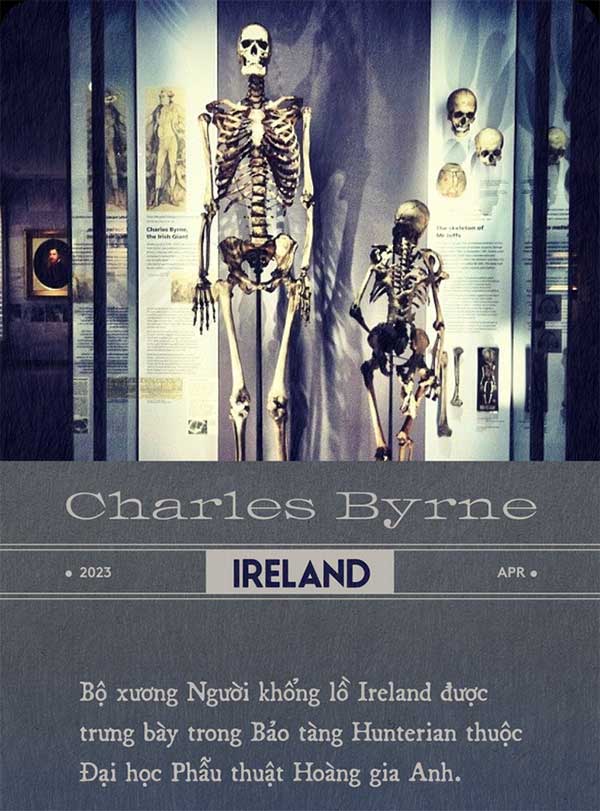

In 1793, John Hunter died at the age of 65 from a heart attack. His entire collection was purchased by the government. They entrusted the estate to the Royal College of Surgeons, tasked with turning it into an anatomical museum named Hunterian.

In this way, Byrne’s skeleton stood there for over 200 years—challenging ethical, scientific, and legal principles.

No one knew what to do with Byrne’s remains. The museum claimed the skeleton was their property, while lawyers argued that everyone should respect Byrne’s wish to be buried at sea while he was alive.

Scientists opposed this, stating they needed to keep the skeleton for research on gigantism, knowledge that would benefit future generations suffering from similar conditions as Byrne.

However, ethicists argued that since scientists had extracted his DNA, the Irish Giant should be allowed to rest in peace.

Yet how Byrne should be allowed to rest is a new question.

Some suggested he should be buried in his hometown, others believed he should be buried at sea as per his wishes, while some argued that the Hunterian Museum should simply put Byrne away and stop displaying him as a specimen.

For two decades, medical ethicists, lawyers, and even those claiming to be Byrne’s living relatives have been unable to decide the fate of his remains. The case of the Irish Giant has become one of the largest controversies in the history of British medicine.

Seeking Rest After Nearly 250 Years

Powerless to argue for an answer regarding the fate of Byrne’s skeleton, in 2011, the British Medical Journal (BMJ) conducted a vote within the medical community.

The idea was proposed by Len Doyal, an honorary professor of Medical Ethics at the University of London, and law lecturer Thomas Muinzer, in an article titled: “Should the Irish Giant’s Skeleton be Buried at Sea?”

The survey results showed that 55.6% voted in favor of that idea. 13.17% supported stopping the display of Byrne’s skeleton but keeping it for research. 31.55% of voters said the status quo should remain.

The influence of the BMJ article that year prompted the Royal College of Surgeons to convene a council meeting to determine the fate of Byrne’s remains. However, after the meeting concluded, the decision was made to continue displaying the ill-fated giant.

In 2013, an article published in the International Journal of Cultural Property Law further addressed the legal issues regarding Byrne’s remains. The researchers traveled back to the village of Littlebridge, where the Irish Giant was born, hoping to find descendants related to him.

However, the search yielded no positive results. Some people with gigantism in Ireland, claiming to be distant relatives of Byrne, also did not have matching gene sequences to be recognized. The authors thus could only call for the Hunterian Museum to return the skeleton to Littlebridge, the place where the Irish Giant was born. They argued he should be buried there.

Dame Hilary Mantel, the author of the novel “The Giant, O’Brien“, which narrates the life of Charles Byrne, expressed her agreement: “I believe Byrne initially wanted his body to be buried at sea simply to escape the reach of Dr. Hunter. If he were allowed to leave the museum now, I think he would want to be buried back home in Ireland.“

By 2021, the drama surrounding the remains of Byrne continued to escalate. This was highlighted in a study by Dr. Mary Lowth, a physician and legal scholar at King’s College London.

Writing in the journal Medical Law, Mary cited English law, which for centuries has treated corpses as persons. When an individual donates their body to science, that body deserves to be treated like a human being and has the rights of a human.

Therefore, when Hunter stole Byrne’s body, he did not commit theft of property but rather abducted a person. At the Hunterian Museum, Byrne was not only displayed but was also held captive for 200 years.

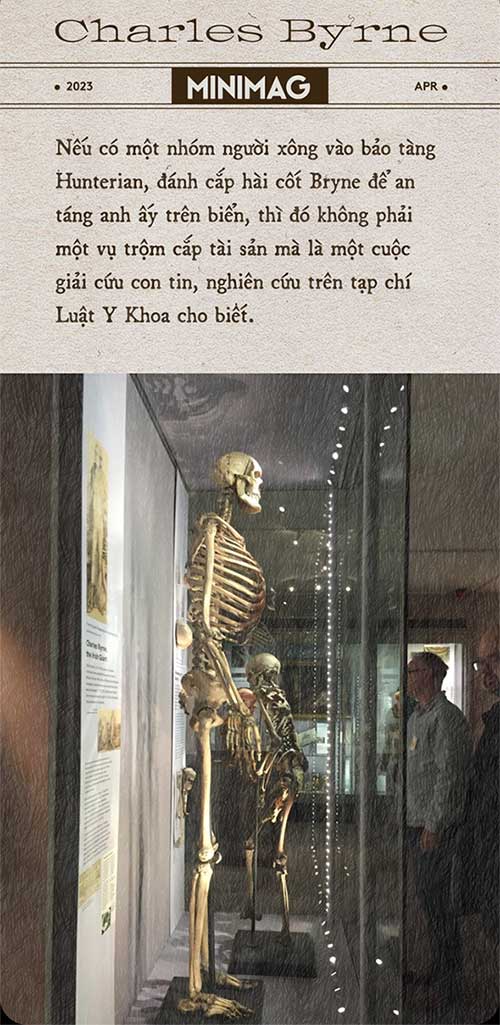

These circumstances pave the way for a scenario where, if a group were to break into the museum and steal Byrne’s remains to bury him at sea as he wished, it would not be considered theft. Instead, these individuals would be undertaking a hostage rescue mission.

If they completed all the legal procedures related to a sea burial, this group of grave robbers could not be prosecuted by law.

Mary’s research was conducted while the Hunterian Museum was closed for three years for renovations. In January, as they prepared to reopen, the Royal College of Surgeons of England issued a surprising announcement.

They stated that the public display of the skeleton of the Irish Giant would be suspended. However, the pressure was still not strong enough for Byrne to be “freed“. He would remain stored somewhere in the Hunterian Museum’s archives for scientific purposes.

“During the museum’s closure, the Board of the Hunterian Collection discussed the sensitivities and differing viewpoints surrounding the display and retention of Charles Byrne’s skeleton“, the announcement read.

“The Commissioners agreed that Charles Byrne’s skeleton will not be displayed in the Hunterian Museum after the renovation process, but it will still be used whenever necessary for legitimate medical research on pituitary disease or giantism.“

With over 20 years of persistent advocacy for Byrne’s rights, Muinzer and Professor Doyal were the first to welcome this decision. The Irish Giant has finally found a space to rest.

“But we suspect the museum will still allow medical students to view the skeleton privately“, Muinzer stated. “This once again goes against his wishes. We believe Byrne’s skeleton should still be buried at sea.“