In Chinese historical dramas, we often see young scholars referred to as “tú tài.” But do you really understand the status of a “tú tài”?

The Path to Becoming a Tú Tài

The term “tú tài” originated during the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, initially used as a title for those of exceptional talent.

From the Han Dynasty, tú tài became candidates for official positions; however, most tú tài of that time came from noble families, making it very difficult for ordinary people to be recommended. Nevertheless, this did not hinder the development of the tú tài status.

After passing the tú tài examination, one could become an official. (Illustrative image).

During the Sui and Tang Dynasties, the establishment of the imperial examination system elevated the status of the tú tài to unprecedented heights. The examination was divided into “three categories and nine ranks,” with the tú tài at the top of the academic hierarchy and holding the highest status. After passing the tú tài examination, individuals could become officials, making the tú tài an aspiration pursued by the intellectual elite.

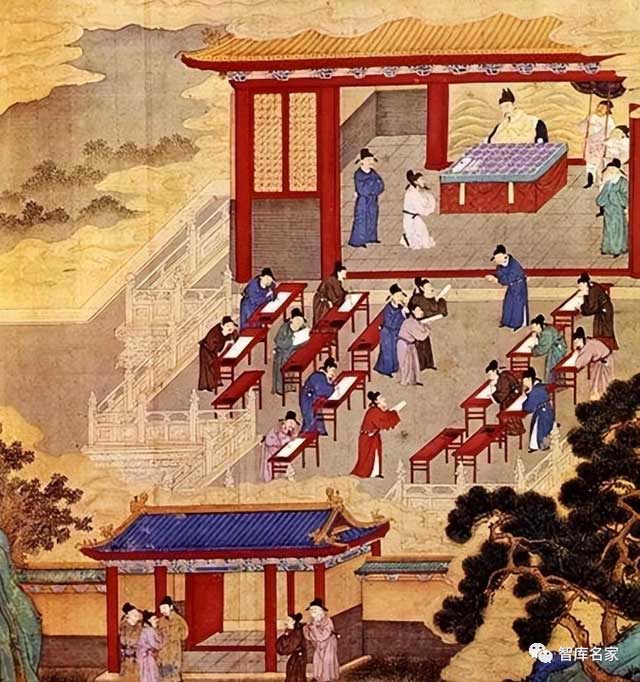

However, with the continuous adjustments of the examination system, tú tài became the most basic level. To participate in higher-level imperial examinations for the top scholar, the second rank, and the third rank, one must first become a tú tài. During this period, tú tài were expected to possess not only extensive knowledge but also good moral character and a sense of social responsibility. They held a high status in society and were respected by all.

The imperial examination system broke the monopoly of noble families in selecting officials, creating opportunities for many ordinary people to change their fates through diligent study.

The status of tú tài has evolved through various stages in Chinese history, from a respected title for talented individuals to the most basic level in later imperial examinations. The title of tú tài has always accompanied the growth and development of the elite intellectual class. They used their wisdom and talents to make significant contributions to social progress and became an important part of Chinese history.

The examinations were strict and meticulous to discover talents for the country. (Illustrative image).

What Level of Education Did Tú Tài Represent?

Historical tú tài can be considered treasures within the imperial examination system. The examinations were extremely rigorous, and the selection process was meticulous, comparable to the admission standards of modern top universities.

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, competition in the imperial examinations was particularly fierce, with hundreds of thousands of tú tài vying for only 20,000 spots, making the acceptance rate for tú tài across China significantly lower than before.

In contrast to modern high school students, who only need to study three years of textbook knowledge, the educational path of the tú tài was long and filled with challenges. They had to study not only collections of classical and historical works but also astronomy, geography, and various schools of thought. This profound knowledge required extensive reading and in-depth study to fully understand.

Tú tài held a high status in society. They were not only disseminators of knowledge but also moral exemplars. Locally, they held teaching positions and passed their knowledge to future generations, earning high respect. This is similar to the modern teaching profession. From this perspective, we can compare tú tài to contemporary individuals with master’s degrees.

Tú tài held a high status in society. (Illustrative image).

However, the requirements for the imperial examinations were extremely high concerning literary talent and writing skills. This is why tú tài had to read a vast number of classical texts and study writing techniques in depth.

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the average age of a successful tú tài was around 24. Considering the volume and difficulty of the knowledge they needed to master, this is almost a remarkable feat. In contrast, modern college entrance examinations focus more on applying textbook knowledge and solving objective problems without placing much emphasis on literary achievements.

Importantly, tú tài needed to delve into classical Confucian works while preparing for the examinations, a deep study of a specific field of knowledge akin to modern postgraduate education. Therefore, we could even compare ancient tú tài to senior experts with doctoral degrees.

In summary, tú tài were undoubtedly exceptional talents selected from hundreds of thousands. Their efforts and knowledge, in some respects, far surpassed those of modern college students. Thus, they held a crucial position in the political system of their time.