A genetic analysis offers new insights into the identity of a Mesolithic hunter-gatherer who died 9,000 years ago.

In 1934, workers in Germany discovered a double grave of a woman positioned sitting with an infant between her legs. Due to the abundance of artifacts surrounding the two individuals, archaeologists concluded that the woman may have been a shaman who died around 9,000 years ago during the Neolithic period. However, her true identity and her relationship with the child remained a mystery.

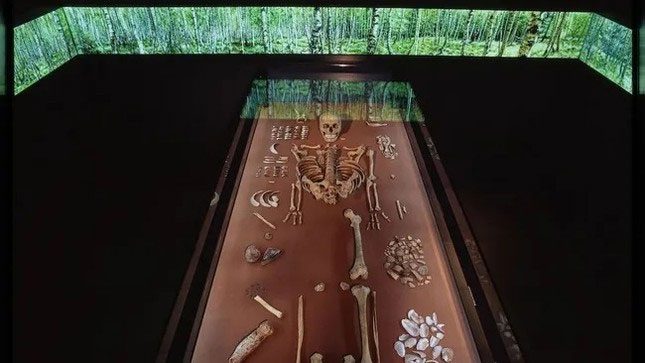

A part of the exhibition at the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle (Saale), Germany, about the double grave. (Image source: LDA Sachsen-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták)

Now, new genetic research has revealed a new clue: The shaman buried in Bad Dürrenberg, a town in eastern Germany, was not the mother of the child but a relative distantly connected across four to five generations.

Co-author of the study, Wolfgang Haak, head of the Genetics Department at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, stated: “We sequenced the entire genome of this woman who lived around 9,000 years ago. This Neolithic woman from Bad Dürrenberg carries a genetic hallmark characteristic of Western hunter-gatherers.”

An analysis showed that the woman was approximately 30 to 40 years old at the time of death, had a slender build, and was about 1.55 meters tall.

Haak noted: “She had darker hair and skin compared to modern Europeans, and likely had lighter blue eyes. These traits are common among Western hunter-gatherers.”

Researchers also discovered that this woman had muscle loss in her lower limbs and abnormal blood vessels in her skull.

Co-author Jörg Orschiedt, a professor of archaeology at Free University Berlin, Germany, stated: “The bones show very little or no evident muscle attachment, unlike many Neolithic human remains. However, this woman did not have any disabilities or physical limitations in any form.”

The researchers also identified a rare anatomical anomaly at the base of the woman’s skull that could lead to compression of the vertebral arteries in a certain position. This might result in mild neurological phenomena, with possible consequences such as nystagmus. This perhaps impacted the shamanic status of this woman.

The genetic analysis concluded that the child buried alongside her was related to the woman but separated by several generations.

Haak explained: “This means that the two were not mother and child as previously hypothesized. The woman could have been the great-grandmother of the boy, and the boy was added to his ancestor’s grave decades later. It is also possible that they were distantly related (both sharing a common ancestor from two to three generations prior).”

Although this discovery was made in the 1930s, this new research contributes many new details relevant to the Neolithic period and paints a more detailed picture of the last hunter-gatherer groups in Europe.