According to a scientific article published last week on CNN’s news site, the bodies of the starfish we see are not their actual main bodies.

As stated in the article, the heads of most animal species are easily identifiable, but so far scientists have not been able to confirm the same for starfish.

A starfish has five identical “arms” with a layer of “tube feet” underneath that help the creature move along the ocean floor. Naturalists wonder whether it is possible to determine front from back in starfish, and whether they even have heads.

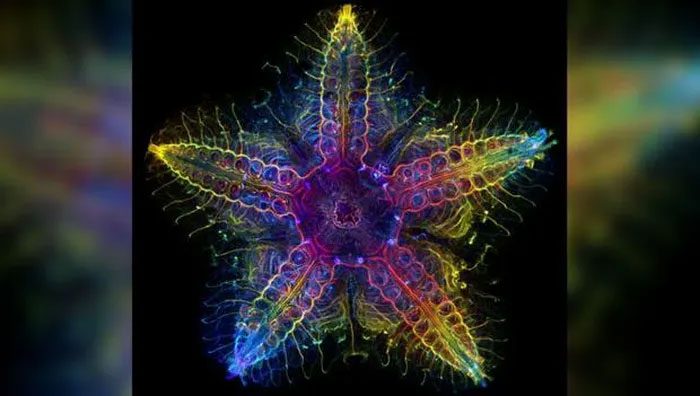

A starfish.

However, new genetic research suggests the opposite: Starfish are largely heads without bodies or tails, and they likely lost those body parts through the process of evolution over time.

Researchers noted that the bizarre fossils of starfish ancestors, which seemingly had some form of body, could reveal much about their evolutionary history based on these new findings.

These discoveries were published on November 1 in the journal Nature.

Laurent Formery, the lead author of the study and a former postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley, stated: “It’s as if the starfish completely lost a trunk and can be most simply described as just a head crawling along the ocean floor. This is not at all what scientists have assumed about this animal.”

These findings, made possible by new gene sequencing methods, could help answer some of the biggest unanswered questions about echinoderms, including their common ancestors with humans and other animals that do not appear similar to them.

Unique Body “Blueprint”

Starfish belong to a group known as echinoderms, which includes sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers.

These unusual animals have a unique “blueprint” for their bodies, organized into five equal parts, which is very different from the symmetrical head-to-tail body structure of “bilaterally symmetrical” animals that have mirrored left and right sides.

Starfish begin as fertilized eggs, hatching into free-floating larvae in the ocean, similar to plankton, for several weeks to months before settling to the ocean floor. There, they undergo a transformation from a bilaterally symmetrical body into a star or pentagon shape.

“This has been a mystery in zoology for centuries,” said senior co-author Christopher Lowe, a marine biologist and developmental biologist at Stanford University. “How can you transition from a bilaterally symmetrical body plan to a five-axis plan, and how can you compare any part of a starfish with our own body plan?”

The “blueprint” for the bilateral bodies of most animal species arises from genetic activities at the molecular level found in the head and body, or regions within the main body. That is why vertebrates—such as humans—and many invertebrates, including insects, share similar “programming” in their genetics.

This discovery was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1995.

However, echinoderms also share a common ancestor with “bilaterally symmetrical” animals, which adds to the complexity of the “puzzle” that researchers are trying to solve.

Co-author Dr. Jeff Thompson, a lecturer at the University of Southampton, stated: “How different body parts of echinoderms relate to those we see in other animal groups remains a mystery to scientists throughout our study of them.”

“In their bilaterally symmetrical relatives, the body is divided into head, body, and tail. But just looking at a starfish, it’s impossible to see how those parts relate to the bodies of bilaterally symmetrical animals.”

Decoding the Echinoderm Species

The researchers conducting this new study utilized computed tomography to capture unprecedented three-dimensional images of starfish shapes and structures.

Then, the research team employed advanced analytical techniques to detect where genes are expressed in the tissues and identify specific RNA sequences within the cells. Gene expression occurs when the information within a gene becomes functional.

Nervous system image of a starfish during analysis, provided by author Laurent Formery. (Photo: CNN/Screenshot).

Lowe noted: “If you strip away the skin of an animal and look at the genes related to defining head and tail, the same genes encode for those body regions in all animal groups. So we bypassed anatomy and asked: Is there a hidden molecular axis beneath all this strange anatomy, and what is its role in how starfish form their five-point body plan?”

In summary, the data created a 3D map to identify where genes are expressed as starfish develop and grow. The team was able to identify genes that control the development of the starfish’s epidermis, including its skin and nervous system.

Genetic markers related to head development were found throughout the starfish, particularly concentrated in the center of the star and at the center of each arm.

However, gene expression in the body and tail was virtually absent, suggesting that starfish “exhibit the most striking example of separation between the head and body that we know of today,” according to lead author Formery, who is also a researcher at the Chan Zuckerberg BioHub, a non-profit research organization in San Francisco.

The research was funded by the Chan Zuckerberg BioHub, co-founded in 2021 by Dr. Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg, along with NASA, the National Science Foundation, and the Leverhulme Trust.

Thompson stated: “When we compared gene expression in starfish with other animal groups, such as vertebrates, it seems that a key part of the body plan is missing. Genes typically associated with the shape of the animal’s body are not expressed in the epidermis. It appears that the entire echinoderm body plan is roughly equivalent to the head in other animal groups.”

Starfish and other echinoderms may have developed their unique body structures after their ancestors lost their body parts, allowing them to move and forage differently from other animals.

Thompson concluded: “Our study tells us that the echinoderm body plan evolved in a more complex way than we previously thought, and there is still much to learn about these fascinating creatures. As someone who has studied them for the past decade, these findings have completely changed the way I think about this group of animals.”