The energy from the massive impact caused the meteorite to evaporate completely, triggering a tsunami that swept the ocean floor and submerged coastlines around the world.

66 million years ago, a colossal meteorite struck Earth, ending the age of dinosaurs and causing a global extinction event.

However, according to new research published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, this was not the largest impact event ever to occur on our planet.

The Devastating Impact of a Giant Meteorite

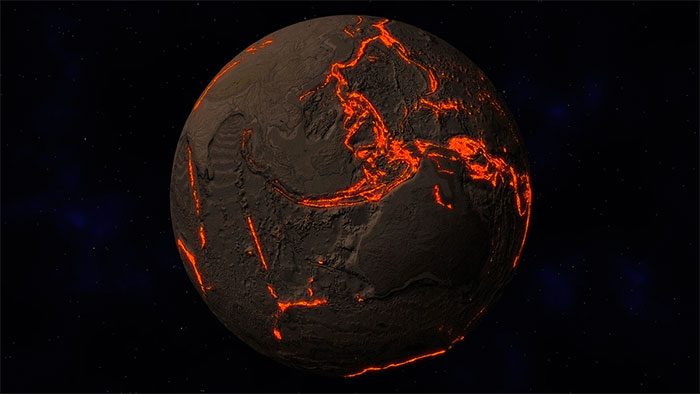

Illustration of a meteorite colliding with Earth – (Image: SciTechDaily).

According to the study, about 3.26 billion years ago, a meteorite over 200 times larger impacted Earth, causing devastation on an even more terrifying scale.

Surprisingly, this catastrophe may have played a crucial role in the early evolution of life by providing essential nutrients for bacteria and ancient single-celled organisms.

Scientists from Harvard University, led by geologist Nadja Drabon, uncovered evidence of this impact through ancient rock layers in the Barberton Greenstone Belt – a region in Northeast South Africa.

Geochemical signs and preserved marine bacterial fossils in the rocks indicate that rather than being destroyed, life not only recovered but thrived following this horrific impact.

The meteorite that struck Earth around 3.26 billion years ago is estimated to have a diameter of 37-58 km, significantly larger than the meteorite that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. This type of meteorite, scientifically known as a carbonaceous chondrite, contains high levels of carbon and phosphorus – key elements for life.

The energy from the colossal impact caused the meteorite to completely vaporize along with the sediment and rock it collided with, creating a cloud of dust and vapor that enveloped the entire Earth, turning the sky black within hours.

Moreover, the gigantic tsunami generated by the impact swept away the ocean floor and submerged coastlines globally. Ocean surface temperatures rose so high that the upper layer of water began to boil, creating a horrific scene of destruction.

“A Fertilizer Bomb” for Primitive Life

Tectonic traces of Earth found in sediments dating back 3.2 billion years – (Image: Visdia/Getty Images).

Despite the terrifying images of near-total devastation, scientists believe that this impact acted like a “huge fertilizer bomb” for primitive life.

After the dust settled and temperatures returned to normal, the meteorite provided Earth with a substantial amount of phosphorus – an extremely important nutrient for bacteria. At the same time, the tsunami mixed iron-rich deep waters with shallow areas, creating a perfect environment for bacteria and ancient single-celled organisms to thrive.

Scientist Nadja Drabon stated: “We often think of meteorite impacts as catastrophic events that destroy life. However, in the context of 3.2 billion years ago, when life was still very simple, such impacts may have facilitated the development of bacteria and single-celled organisms.”

During the Paleoarchean era – the period when the impact occurred, Earth’s surface was predominantly ocean, with only a few volcanoes and landmasses emerging. There was no oxygen in the atmosphere, and cellular organisms had yet to appear. Life at that time consisted mainly of bacteria and single-celled organisms, which were capable of rapid recovery and adaptation to the post-catastrophe environment.

Although the impact may have caused significant destruction to organisms dependent on sunlight and those in shallow waters, research indicates that life rebounded quite quickly. Within just a few years to a few decades after the atmosphere and oceans stabilized, bacteria thrived once more.

Geological evidence from the Barberton Greenstone Belt – including chemical traces of the meteorite, small structures formed from melted rock, and sediment layers on the ocean floor – has helped scientists gain a better understanding of the impact’s effects and how life survived this disaster.

Geologist Andrew Knoll from Harvard University and co-author of the study stated: “Life on Earth at that time demonstrated an incredible resilience to such colossal impacts. This is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of life, even in its earliest stages.”

This new discovery not only enhances our understanding of the impacts of meteorite collisions in Earth’s history but also sheds light on their role in driving the evolution of life.

From a scientific perspective, what may seem like a catastrophic destruction could actually be a powerful catalyst for the development and evolution of primitive organisms, contributing to the diversity of life as we know it today.