The Supergiant Star Betelgeuse continues to thrill astronomers with noticeable changes since April 2023, hinting at an explosion powerful enough to light up the night sky of Earth.

Betelgeuse is one of the brightest stars in the Earth’s sky, radiating a “ghostly” red hue and located in the constellation Orion. It has captivated astronomers for centuries, with the earliest records dating back over 2,100 years to the Chinese scholar Sima Qian.

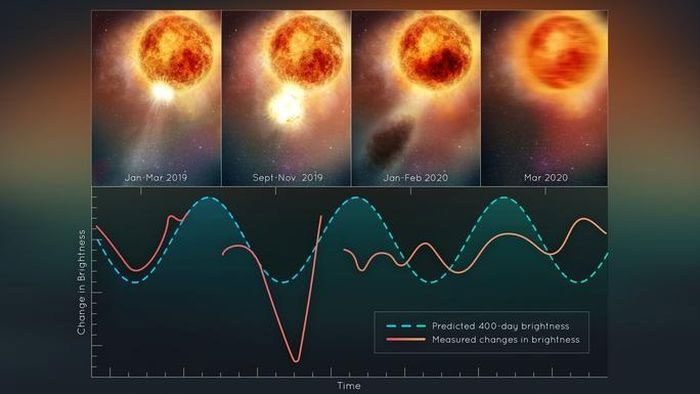

Different “transformations” of Betelgeuse, including material ejections and periods of brightness followed by dimming, possibly obscured by dust ejected from the star – (Image: NASA).

Since April, the star has ascended from the 10th brightest position in the night sky to 7th, due to a brightness surge of 140%, according to Betelgeuse Status – an account on Twitter that aggregates professional and amateur astronomers who closely monitor this mysterious star.

According to Space, the continuous fluctuations of Betelgeuse—sometimes dimmer, sometimes brighter—since 2019 have led astronomers worldwide to speculate that it may be nearing its death throes.

In Sima Qian’s records, this bright star was described as yellow, while today we observe it as red, indicating that this giant star has gradually progressed into the “red giant” phase over the past two millennia. This is the final phase of swelling before it explodes into a supernova.

If it explodes, the light from Betelgeuse could be bright enough to rival a full moon, illuminating the night sky of Earth or drawing attention even during the day.

Fortunately, at a distance of 650 light-years, this supernova is unlikely to impact Earth like some ancient supernovae that were closer and linked to mass extinction events.

Astronomers worldwide are divided into two “camps”: one believes it could explode at any time, while the other thinks it still has some time left.

“Our best models suggest that Betelgeuse is in the phase of burning helium into carbon and oxygen in its core. That means it could still have tens or hundreds of thousands of years before it detonates—if that model is correct,” says astrophysicist Morgan MacLeod from Harvard University.