The successful development of an effective vaccine against H5N1, along with the stockpiling of antiviral medications, is one of the top priorities that all governments around the world aspire to in the fight against the avian flu pandemic.

The medical journal The Lancet announced on February 2, 2006, promising results from a trial of a vaccine against H5N1, the avian influenza virus that re-emerged in 1997 in Hong Kong and is currently causing outbreaks of avian flu in Southeast Asia and Turkey.

Suryaprakash Sambhara, a researcher at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, and Suresh Mital from Purdue University in Indiana reported success in developing a pandemic vaccine effective against multiple distinct H5N1 strains in mice using genetic technology.

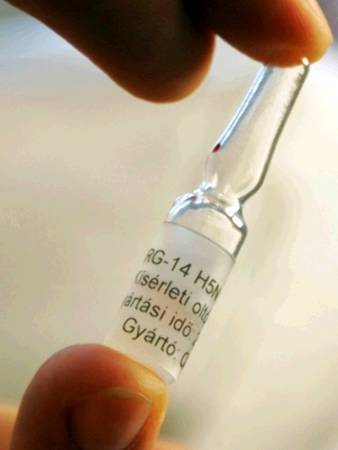

Avian flu vaccine manufactured in France.

The highly pathogenic avian influenza virus has been confirmed to cause approximately 152 human cases, with a mortality rate exceeding 50% since 2004.

A genetic combination between avian and human viruses, or mutations of the current H5N1 strain in poultry, could potentially create a new virus strain.

This type of virus could transmit between humans and lead to a pandemic.

Repeated and High-Dose Administration

Currently, several vaccines have been developed to combat the H5N1 virus, but they have shown limited protective efficacy in tested subjects: not only do these vaccines generate a small amount of antibodies in the body, but even with repeated vaccinations and high doses, the results remain modest. Moreover, they should be considered as pre-pandemic vaccines that are entirely ineffective against future viruses that adapt to humans.

|

| H5N1 virus research in the laboratory (Image from foreign website). |

Another common obstacle faced in this strategy to develop standard vaccines from inactivated viruses is the need for fertilized chicken eggs as a medium for virus propagation. However, in the event of a pandemic, there is an urgent need to protect 1.2 billion people swiftly. Scientist Suryaprakash Sambhara notes: “Researchers estimate that 4 billion eggs are needed to cultivate the virus, and it takes about 6 months to produce a classical egg-based vaccine.” This timeframe could be reduced to less than a month with new technologies for genetically engineered vaccine prototypes.

Common Influenza Virus

American researchers have envisioned, created, and developed a genetically engineered inactivated common influenza virus that carries the hemagglutinin gene H5 from the H5N1 virus in Hong Kong. Subsequent evaluation showed that this vector virus effectively produced the H5 protein in human embryonic cells.

Ten-week-old experimental mice received two vaccinations spaced 4 weeks apart, either with the experimental vaccine or with another previously tested vaccine for humans. To test the efficacy of the new product, groups of mice were exposed to a lethal dose of the wild-type Hong Kong virus 4 weeks after vaccination.

Results showed that mice protected by the new vaccine produced significantly more antibodies and had up to 8 times more immune cells. All vaccinated mice survived reinfection with the virus, including different strains.

Dr. Sambhara assesses: “This approach is an effective vaccination strategy against currently circulating high-pathogenic viruses and new variants, as part of the pandemic preparedness program.”