At the end of the 18th century, over 150 scientists accompanied Napoleon to Egypt for research and exploration, leading to numerous new discoveries and insights.

When he invaded Egypt in July 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte brought along not only thousands of soldiers but also recruited more than 150 scientists. Their mission was to study and exploit the region. On August 23, 1798, the scientific society named the Institut d’Égypte held its first meeting in Cairo, with Napoleon serving as the first vice president. However, after several setbacks in Egypt, Napoleon returned to France in 1799, leaving many scientists stranded.

Illustration of Napoleon standing before the Sphinx. (Photo: Jean-Léon Gérôme)

Despite the challenges, engineers, mathematicians, naturalists, and other experts dedicated nearly three years to surveying, documenting, and collecting everything from artifacts to mummies and species unknown to the West. Their work led to several new discoveries, helping to formalize disciplines like archaeology and fuel a passion for Egyptology.

Discovery of Reversible Chemical Reactions

Previously, the concept of reversible chemical reactions was not widely accepted. However, chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet found compelling evidence for this viewpoint while studying salts in the lakes of the Natron Valley.

The limestone in the lakes was covered by natron, a natural salt that the Egyptians used for mummification due to its ability to absorb moisture and dissolve fats. Berthollet discovered that limestone containing calcium carbonate reacted chemically with salt, or sodium chloride, to create natron. While earlier chemists had known that the reverse reaction could occur under laboratory conditions, Berthollet provided substantial evidence for it.

Contributing to the Formalization of Archaeology

During Napoleon’s time, archaeology was not yet an official science. Most scientists lacked experience with artifacts, and many sites remained buried under sand, waiting to be excavated.

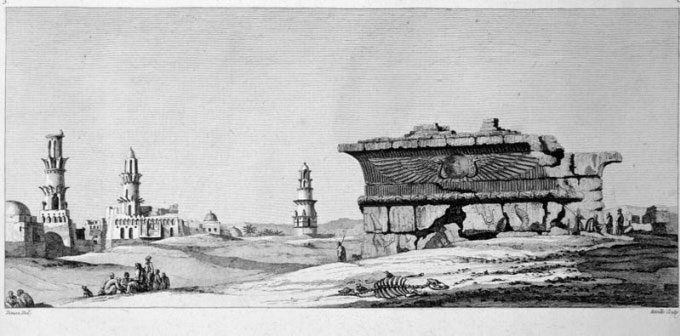

Artist and writer Dominique-Vivant Denon was amazed by the ancient relics he encountered. He returned to France with Napoleon and quickly published a book featuring descriptions and illustrations titled Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt. His drawings and descriptions of temples and ruins in Thebes, Esna, Edfu, and Karnak became famous and highly regarded.

A New Method for Classifying Insects

Upon returning to France, botanist Jules-César Savigny needed to organize the 1,500 insect species he had collected. At that time, there was no systematic method to distinguish one species of butterfly from another. Thus, Savigny devised a new method.

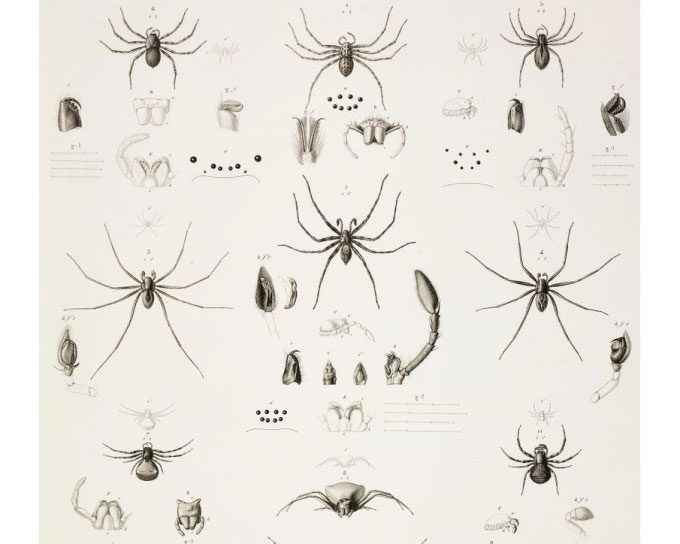

He observed that the mouthparts of these insects were sufficiently distinct to categorize them into different species. He carefully studied the tiny jaws of the insects and illustrated over 1,000 specimens, some only a centimeter long. Savigny applied similar precision to spiders, worms, and other invertebrates. Some of his classification methods are still in use today.

Intricate illustrations of Savigny’s arachnids in the book Description de l’Egypte. (Photo: De Agostini Editorial)

Discovery of a New Crocodile Species

Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire believed there were two species of crocodiles in the Nile River. He was also an excellent collector, like Savigny. While in Egypt, he studied bats, geese, turtles, and many other creatures. Geoffroy’s hypotheses often annoyed other naturalists, including his claim that a mummified crocodile he collected from Egypt belonged to a separate species.

Geoffroy stated that its jaw was completely different from that of the Nile crocodile and noted that it was also less aggressive. His colleagues doubted his assertion of a distinct crocodile species. However, over 200 years later, biologist Evon Hekkala and her research team analyzed the DNA of modern crocodiles and several mummified specimens from Geoffroy, confirming the existence of two separate species swimming in the Nile: Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus) and desert crocodiles (Crocodylus suchus).

The Birth of Ophthalmology

French doctors accompanying Napoleon encountered strange diseases in Egypt. One ailment they brought back to Europe was “Egyptian eye disease,” now known as trachoma, which can cause itching, swelling, and lead to blindness. The disease became so widespread that physicians across Europe began studying it.

At that time, ophthalmology was not yet an official branch of study, but the race to discover the origins of trachoma laid the groundwork for its establishment. Eventually, English physician John Vetch realized that pus from inflamed eyes could spread the disease. Upon recognizing the infectious nature of the ailment, Vetch developed preventive measures and treatments that are considered a significant milestone in the history of ophthalmology.

The Rosetta Stone Helps Decipher Hieroglyphs

For centuries, no one could read the hieroglyphs found on the monuments of Egypt. When the Rosetta Stone was discovered during the invasion, the French recognized it could be used as a key for translation.

The stone features three inscriptions in Egyptian hieroglyphs, Demotic script derived from hieroglyphs, and ancient Greek. The three texts were identical, so the Greek portion could assist researchers in deciphering the hieroglyphs. French scholar Jean-Francois Champollion managed to translate them over two decades.

The Birth of Egyptology

Many wealthy individuals in the 18th century collected artifacts as a hobby without truly understanding their function or significance. Napoleon’s scientists explored Egypt with a more scientific perspective.

During that time, many Europeans had heard of the pyramids or the Sphinx, but the ancient temples and monuments of Upper Egypt were still largely unknown. Dominique-Vivant Denon, an artist and writer, traveled alongside Napoleon’s soldiers along the Nile. He recounted a journey around a bend in the river and suddenly witnessing the ancient temples of Karnak and Luxor rising from the ruins of Thebes. “The entire army, suddenly and in unison, was astonished and applauded in excitement,” he wrote.

Drawing of the Edfu temple by Dominique-Vivant Denon. (Photo: Art Media/Print Collector)

Denon returned to France with Napoleon and quickly published the book Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt with descriptions and illustrations. He also recommended sending more scientists to the Nile to document the monuments in greater detail. Napoleon agreed, and two new research teams arrived in Egypt to carry out archaeological missions in September 1799.

The team of architects and young engineers sketched and measured numerous ancient architectural structures. All of these surveys were published in La Description de l’Egypte, an extensive multi-volume work that included maps, hundreds of engravings, and many descriptions of what they learned about Egypt. The series divided Egypt into ancient and modern periods while providing a modern view of ancient Egypt as known to contemporary scholars.

La Description de l’Egypte became extremely famous. The architecture, symbols, and imagery of ancient Egypt even became a fashionable highlight in European art and architecture.

Thanks to the explorations of Napoleon’s scientific team, European fascination with ancient Egypt grew, leading to the establishment of archaeological museums on the continent, starting with the Louvre opening the first Egyptian museum in 1827.

Ultimately, this passion led to the emergence of Egyptology, a field that significantly influences modern archaeology. “Napoleon’s scholars and engineers are most remembered as those who helped make archaeology a scientific discipline,” author Nina Burleigh writes in her book Mirage.

Invention of the Engraving Machine to Accelerate Printing

Upon returning to France, many scientists participated in compiling the multi-volume work Description de l’Égypte, which spanned 7,000 pages of their observations and research in Egypt. To expedite the labor-intensive engraving process, engineer Nicolas-Jacques Conté developed a machine that partially automated the process.

To print hundreds of illustrations, engravers first had to transfer them to copper plates. With the plates containing images of monuments, Conté’s machine could engrave the sky in the background. The engravers could also set the machine to create clouds. What used to take 6 to 8 months could now be completed in just a few days.

However, the work remained quite labor-intensive and was considered the most ambitious project in France in the early 19th century. The first volume was printed in 1809, and the final volume was released in the late 1820s, nearly a decade after Napoleon’s death.

- Why did NASA take 3 months just to open two locks on the container holding rocks and soil collected from a location 6.2 billion kilometers away from Earth?

- Why are donkeys raised in many parts of the United States to protect livestock instead of using sheepdogs?

- “The Cross-Time Assassin” 13 billion years old that killed an entire galaxy