In 1996, the sheep Dolly created a global sensation after becoming the first mammal to be successfully cloned from an adult cell. Many commentators suggested that this would catalyze a golden age of cloning. Speculations arose that human cloning was only a few years away.

Some believed that human cloning could play a role in eliminating genetic diseases, while others thought that the cloning process could ultimately eradicate congenital disabilities. However, a study conducted by a group of French scientists in 1999 indicated that cloning could actually increase the risk of congenital disabilities.

All these claims are unfounded; the most important thing is to supplement successful cases of human cloning as evidence since Dolly’s time. In 2002, Brigitte Boisselier, a French chemist and a devout supporter of Raëlism (a UFO-based religion suggesting that aliens created humanity), claimed that she and a team of scientists had successfully cloned the first human, named Eve. However, it is noteworthy that Boisselier did not want – or could not – provide any evidence for this, and thus it was regarded by many as a hoax.

Dolly the sheep.

Dolly the sheep.

The question arises: why, nearly 30 years after Dolly, has human cloning not yet occurred? Is it primarily due to ethical reasons, technological barriers, or simply because it is not worth pursuing?

The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) states that cloning is a broad term, as it can be used to describe a range of processes and approaches, but generally aims to create genetically identical replicas of a biological entity.

According to NHGRI, any human cloning effort would utilize “reproductive cloning” techniques – an approach that uses mature somatic cells, most likely skin cells. DNA extracted from this cell would be inserted into an egg cell from a donor, which has had its nucleus containing its own DNA removed. The egg would then begin to develop in vitro before being implanted into the uterus of an adult woman to form a fetus.

However, while scientists have cloned many mammal species, including livestock, goats, rabbits, and cats, humans remain absent from this list. Hank Greely, a professor of law and genetics at Stanford University, specializing in ethical, legal, and social issues arising from advances in biological science, states that up to this point, there are no valid reasons for cloning a human being. Human cloning is an exceptionally dramatic act and one of the most hotly debated topics concerning bioethics in the U.S.

Ethical concerns surrounding human cloning are also quite diverse. Among them, potential issues include risks related to psychological, social, and physiological factors, meaning cloning could lead to a very high likelihood of loss of life, or concerns surrounding the use of cloning by proponents of eugenics. Moreover, cloning could be seen as a violation of principles regarding human dignity, freedom, and equality.

To date, there are no valid reasons for cloning a human.

To date, there are no valid reasons for cloning a human.

Additionally, the historical cloning of mammals has led to very high mortality rates and developmental abnormalities in cloned species. Another core issue with human cloning is that instead of creating a copy of the original person, it would produce an individual with their own thoughts and perspectives. We are all familiar with identical twins, who are replicas of each other; thus, we also know that clones are not the same person. A clone of a human would only have the same genetic makeup as that person, but would not share other traits such as personality, ethics, or sense of humor: these are unique to each individual.

Humans are not simply a product of DNA; they are also influenced by many other factors. While it may be possible to replicate genetic material, it is impossible to accurately recreate living environments, provide identical upbringing, or ensure two individuals have the same life experiences.

If scientists were to clone a human, what benefits would there be, scientifically or otherwise? Researchers emphasize that ethical concerns cannot be overlooked. However, if ethical considerations were entirely disregarded, a theoretical benefit could be the creation of genetically identical humans for research purposes.

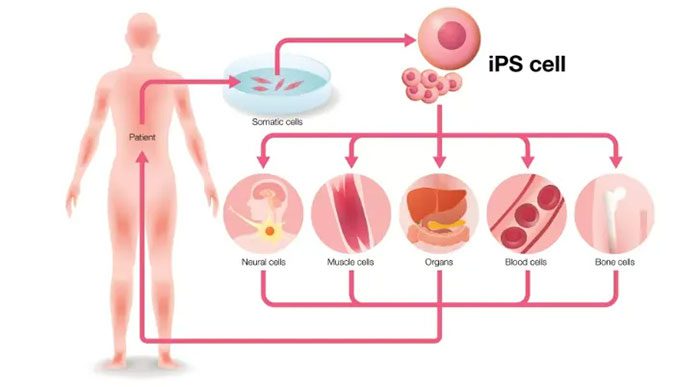

Greely also asserts that, regardless of personal opinions, some potential benefits associated with human cloning seem superfluous given scientific advancements in other areas. He points out that the idea of using cloned embryos for purposes beyond creating newborns, such as producing embryonic stem cells identical to those of the donor, was widely discussed in the early 2000s, but this research avenue has become less relevant and has not expanded. After 2006, the year the so-called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were discovered, which are “mature” cells reprogrammed to resemble embryonic cells using just four genetic factors.

Shinya Yamanaka, a Japanese stem cell researcher and Nobel Prize winner in 2012, discovered this while finding a way to revert mature mouse cells back to an embryonic-like state using just four genetic factors. A year later, Yamanaka, along with renowned American biologist James Thompson, managed to do the same with human cells.

A diagram showing induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and their potential for regenerative medicine

Thus, rather than using embryos, we can effectively achieve similar outcomes using skin cells. This development in iPSC technology has fundamentally rendered the concept of using cloned embryos both unnecessary and scientifically inferior.

Currently, iPSCs can be used to study disease models, explore therapeutic drugs, and regenerative medicine. Greely also suggests that human cloning may no longer be an appealing field of scientific research, which may explain the lack of development in recent years. He notes that editing germline genes has now become a more interesting topic for many, as they are intrigued by the concept of creating “super babies.” Germline editing, or germline engineering, refers to a series of processes that create permanent changes to an individual’s genes. If we can effectively make these changes to become hereditary, it means they will be passed down from parents to their offspring.

However, such editing is still not fully understood and is controversial. For instance, the European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies states that ethics and human rights must guide any activities involving gene editing technologies in humans, and the application of gene editing technologies to human embryos raises numerous ethical, social, and safety issues, especially since any modifications to the human genome could be passed on to future generations.

Additionally, there is strong support for such engineering and editing technologies to provide more comprehensive insights into the causes of diseases and future treatment options, significant potential for research in this field, and improvement of human health. George Church, a geneticist and molecular engineer at Harvard University, is one of the advocates, stating that this field could attract greater interest from the scientific community in the future, especially in comparison to conventional cloning.

Germline gene editing is often more precise, potentially involving more genes, and more efficiently distributed across all cells compared to somatic gene editing. However, he still cautions that care is needed and acknowledges that such editing is not yet mastered. Potential limitations that need addressing include safety, efficacy, and fairness for all of us.