New archaeological discoveries reveal the companionship between humans and foxes in South America, which may change our understanding of early animal domestication processes.

Dogs are considered the first animals domesticated by humans, with a strong bond existing between dogs and people for thousands of years. However, dogs are not the only members of the canine family that were kept as pets by ancient people.

A notable archaeological study in South America has found the remains of a fox alongside a human grave dating back 1,500 years. Genetic evidence shows that this fox species shared a diet similar to that of the hunter-gatherers in Patagonia.

Dr. Ophélie Lebrasseur from the University of Oxford stated: “This is a very rare finding as this fox appears to have such a close relationship with individuals in a hunter-gatherer society.”

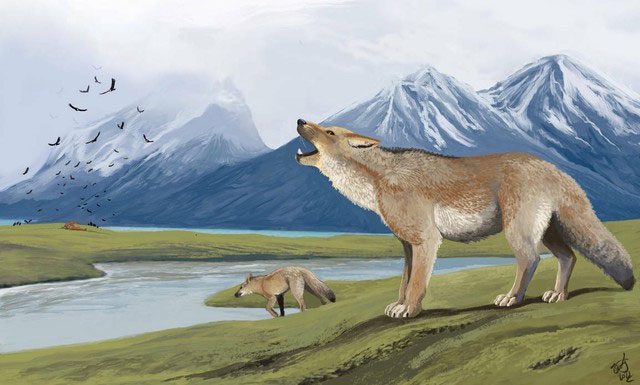

The Dusicyon avus, also known as Darwin’s fox, once inhabited Patagonia, South America, until about 1,000 years ago. Scientists have discovered evidence suggesting that this fox was domesticated by the hunter-gatherers in the area 1,500 years ago.

Examination of the teeth indicates that this ancient domesticated fox belonged to the Dusicyon avus species, an extinct species resembling a wild dog. It was roughly the size of a German Shepherd and closely related to the Falkland Islands wolf (Dusicyon australis), which became extinct in 1867.

Researchers extracted small samples from the forelimb and vertebrae of the animal to analyze its DNA. Although the genetic samples were severely degraded, scientists were still able to reconstruct some of the missing genetic sequences. As a result, they found no matches between these foxes and any living members of the canine family.

This DNA data also refutes the previous notion that the ancient fox hybridized with domestic dogs brought to Patagonia around 1,000 years ago. However, Dusicyon avus is too genetically distinct from domestic dogs to produce hybrids.

The reason for the extinction of Dusicyon avus remains unknown. However, another mystery is why the remains of this fox-like creature were buried alongside humans.

The discovery was made at an archaeological site in Santa Cruz Province, Argentina. Archaeologists found bones and teeth of Darwin’s fox alongside human bones and other artifacts. DNA analysis indicated that this fox species is not related to any living members of the canine family, whether domestic dogs or other South American foxes. This DNA data further supports the idea that these remains belonged to the Dusicyon avus species. It also refutes the earlier idea that the ancient fox hybridized with domestic dogs brought to Patagonia about 1,000 years ago.

Radiocarbon analysis of both fox and human remains showed they were of the same age. Similarly, both types of remains exhibited similar wear patterns, indicating that Dusicyon avus and humans were intentionally buried together.

The isotopes preserved in the teeth of Dusicyon avus suggest its diet included meat, a staple for any wild canine species. However, its diet also included a type of plant similar to corn—food that the buried humans also consumed.

The most plausible explanation seems to be that humans domesticated and raised Dusicyon avus as companions. In fact, wild fox teeth have been found in other ancient human graves in Argentina and Peru. Furthermore, archaeologists have previously discovered small ornaments made from the teeth of South American foxes.

Dusicyon avus is an extinct cerdocyonine canid of the genus Dusicyon, originating from South America during the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs. It was medium to large-sized, comparable to a German Shepherd. It is closely related to the Falkland Islands wolf, which originated from the D. avus population. The range of Dusicyon avus extended across the Pampas and Patagonia in southern and central South America, with an estimated distribution area of about 762,351 km².

This discovery is significant as it provides the first evidence that foxes were domesticated in South America. It also suggests that the process of animal domestication may have occurred earlier and in more places around the world than previously thought.

Moreover, this discovery illustrates that the relationship between humans and foxes is more complex than previously believed. It is possible that hunter-gatherers domesticated Darwin’s fox for companionship, hunting assistance, or fur collection.

Foxes are part of the canine family, Canidae, which also includes domestic dogs, wolves, wild dogs, dingoes, and other canids. However, despite belonging to the same family, dogs (and wolves) belong to the genus Canis, while most fox species belong to the genus Vulpes. There is approximately ten million years of evolutionary separation between domestic dogs and red foxes.