In 1871 in Meidum (Egypt), archaeologists eagerly began excavating the tomb of a prince from ancient times.

They were shocked to find it devastated and empty. Since then, research into tomb robbery during this era has revealed it to be sophisticated, persistent, and alarmingly widespread.

The “Underground” Financial System

Ancient Egyptian society was distinctly stratified, with the main difference between the two primary classes—nobility and commoners—being wealth. While the commoners often faced hunger and lacked adequate food to sustain their families, the nobility lived in extreme abundance and luxury. When members of the elite, especially royal family members, passed away, they were typically buried with countless valuable items.

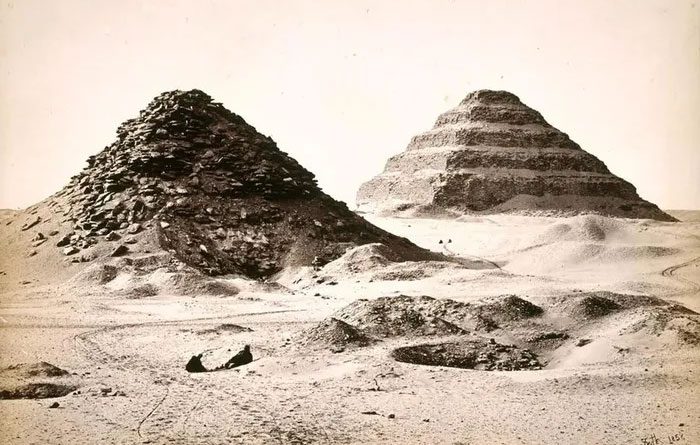

Pyramids are the primary target for tomb robbers. (Photo: Smithsonianmag.com).

“Desperate times breed desperate measures” is a phrase that accurately describes the situation of the commoners in ancient Egypt. During the First (2181 – 2055 BCE) and Second Intermediate Periods (1782 – 1570 BCE), tomb robbery was rampant.

“Evidence from this era shows that tomb robbers were incredibly determined, willing to spend years digging tunnels into tombs they believed contained vast treasures,” stated Betsy M. Bryan, an honorary Egyptologist from Johns Hopkins University in the United States.

After 1871, when archaeologists excavated the tomb of Prince Nefermaat (2575 – 2551 BCE) in Meidum and discovered that Nefermaat’s mummy had been damaged with the surrounding area completely looted, they began to investigate the issue of tomb robbery further.

Through the evidence, they clearly found that tomb robbery was a large underground organization operated by criminals. These individuals cleverly established connections with tomb construction workers, exchanging money for information and bribing stonecutters and craftsmen to leave gaps or replace fragile stones on the walls.

Moreover, they even bribed the tomb guards. The more decentralized the power was (as rulers were busy fighting for control or engaged in wars), the more active they became. Even when faced with threats of curses or dangerous traps, they persisted.

During the New Kingdom (1550 – 1070 BCE), Egypt had to shift from above-ground pyramid burials to underground tombs. They also created a workers’ village, Deir el-Medina, near the Valley of the Kings, to control information leaks. However, this backfired. Many workers, taking advantage of their role sealing the tombs, managed to smuggle out valuable burial goods before closing the tombs.

“Many coffins were not even broken into from the outside, but when opened, the valuable burial items, such as the gold mask on the pharaoh’s face, were missing,” pointed out Aidan Dodson, an Egyptologist from the University of Bristol, UK.

Ancient Egyptian laws imposed severe penalties for tomb robbery; anyone caught trading in burial goods from the pharaoh faced execution by impalement. However, tomb robbers found ways to evade punishment and turned the burial items into commodities that circulated in the market.

For valuable metal artifacts, they melted them down to erase any evidence. For furniture and gold-plated statues, they stripped the precious inlays and gold plating, discarding the rest as worthless. For perfumes, they simply swapped the containers…

Over time, tomb robbery developed into a large organization, forming an “underground” economy. Through this underground economy, they enriched themselves, expanded operations, attracted more members, and made tomb robbery more efficient and streamlined.

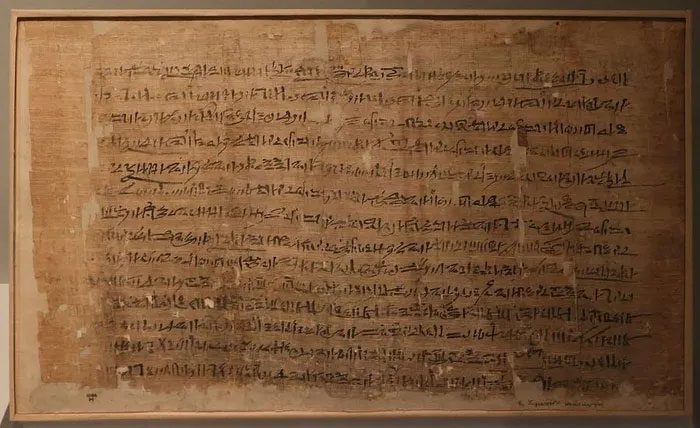

A papyrus roll detailing a tomb robbery during the 20th Dynasty. (Photo: Smithsonianmag.com).

Impossible to Prevent

“The upper-class society of ancient Egypt aimed for eternal life after death, so tombs served as sacred vessels to help them transition to the afterlife,” stated researcher Maria Golia from the United States.

Thus, tomb robbery was deemed one of the gravest offenses, punishable by extremely harsh measures such as hand amputation, impalement, or being staked through the body… yet these punishments were insufficient to deter robbers.

The earliest documented account of tomb robbery was found in a series of papyrus scrolls detailing court proceedings in Thebes during the New Kingdom, specifically the 20th Dynasty (1189 – 1077 BCE).

“We used bronze tools to tunnel into the pyramid and break in from the bottom,” admitted a mason named Amenpanufer. After taking all the gold artifacts, he and his accomplices burned the coffin and divided the spoils.

The 20th Dynasty was the peak of tomb robbery, with numerous royal tomb thefts,” stated Salima Ikram, an Egyptologist from the American University in Cairo. The cause was an unstable society, widespread famine, invasions, and constant power transfers.

However, even before and after this period, tomb robbery remained rampant. During the 18th Dynasty (1550 – 1292 BCE), when Egyptian society was extremely peaceful and prosperous, Pharaoh Tutankhamun also fell victim. Inside the antechamber of his tomb, numerous bags were found scattered about, suggesting that the robbers had been caught red-handed and forced to abandon their loot.

For 3,000 years of ancient Egyptian history, tomb robbery has been a continual problem. After this civilization declined, it morphed into treasure hunting. Over time, Egyptians gradually lost respect for ancient Egyptian beliefs and ceased to fear the curses of the dead. Taking valuable burial items upon discovering ancient tombs became a matter of luck. Egyptian law did not intervene until the late 19th century when archaeologists began protecting excavation sites in the name of research.

“If ancient architects only had one chance to design and build an impregnable tomb, tomb robbers had far too much time to figure out how to break in,” Ikram wrote. Aside from the fading spiritual beliefs, tomb robbery was also justified by the reason of “feeding families.” This led to tomb robbery evolving from a crime to a norm, leaving future generations to suffer the loss of not witnessing a complete ancient Egypt.