The mummification process of ancient Egyptians could remarkably preserve corpses, but the original purpose of mummification may surprise us.

Egyptian mummies have always been a significant testament to human civilization from ancient times and have been the subject of study for historians and scientists for thousands of years. For a long time, it was believed that the mummification technology was created to preserve the bodies of the deceased. Indeed, thanks to mummification, the remains of ancient people from thousands or hundreds of years ago still retain a certain level of integrity, resisting the natural process of decomposition.

It is believed that ancient Egyptians used the mummification method as a way to preserve the body after death. However, researchers from the Manchester Museum at the University of Manchester in the UK have demonstrated that this elaborate burial technique actually served a different purpose: it was a way to “guide” the deceased toward the divine.

Modern humans have yet to fully decode the mummification techniques of ancient Egypt.

Campbell Price, an expert on ancient Egypt and Sudan at the museum, told Live Science that the long-held belief that mummification is solely for preserving the body has deep roots. This idea originated from Victorian-era Western researchers. Scientists of that time believed that ancient Egyptians preserved their dead similarly to how fish are preserved. Their reasoning was quite straightforward, as both processes involved a common element: salt.

However, the salty substance used by ancient Egyptians was different from the salt used to preserve freshly caught products. Known as natron, this natural mineral is a mixture of sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride, and sodium sulfate found abundantly around the lakes near the Nile River, and it served as a key ingredient in the mummification process.

“We also know that natron was used in temple rituals and in the construction of statues of the gods”, Price said. “It was used for purification.”

Price indicated that another material commonly used in mummification was incense, which was also offered as a gift to the gods: “Look at frankincense and myrrh – they appear in the story of Jesus in Christianity. In ancient Egyptian history, we’ve discovered that they were also gifts presented to the gods. Even the word for incense in ancient Egyptian translates to ‘senetjer’, which literally means ‘to make sacred’. When you burn incense in a temple – the house of a deity, it sanctifies the space. By using aromatic resin during mummification, the body becomes a divine entity. That was the ancient mindset: to infuse the body with incense to ‘divinize’ it, rather than merely for preservation purposes.”

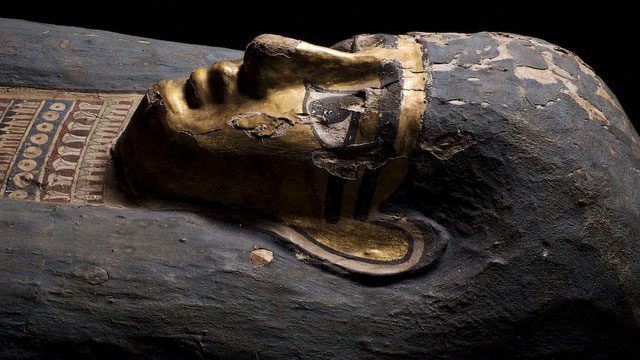

The coffin of Tasheriankh, a 20-year-old woman from the city of Akhmim, who died around 300 BC.

Like the ancient Egyptians, Victorian Egyptologists also believed that the deceased would need their bodies in the afterlife. This belief further reinforced the misunderstanding about mummification.

Price commented: “There is an obsession stemming from Victorian ideas about the need for the deceased’s body to be complete in the afterlife. This includes the removal of internal organs. I think mummification is a ritual that has a much deeper meaning, fundamentally transforming the body into a divine statue as the deceased has been transformed.”