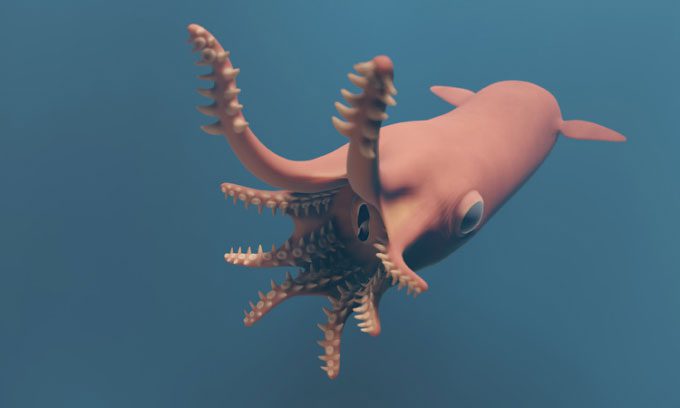

Unlike modern vampire squids, their relatives from the Jurassic period had 8 arms with large suckers to manipulate their prey.

Ancient relatives of the vampire squid had strong suckers to capture prey. (Photo: A. Lethiers/CR2P-SU)

Scientists have for the first time used advanced 3D imaging techniques to examine the details of the feeding suckers of Vampyronassa rhodanica (V. rhodanica), an extinct relative of the modern vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis). The new study, published in the journal Scientific Reports on June 23, reveals unprecedented anatomical features within this creature.

“For the first time, we demonstrate that V. rhodanica possesses a combination of anatomical features that no longer exist today,” said Alison Rowe, a PhD student at the Center for Paleobiology Research (CR2P) in Paris and the lead author of the study.

The three fossil specimens used in the study were excavated from the La Voulte-sur-Rhône Lagerstätte, a fossil site dating back approximately 164 million years in Ardèche, southeastern France. Scientists first examined these specimens in 2002 and identified them as belonging to an unknown species. This creature had 8 arms with large suckers and spines. At that time, experts knew that each arm had a row of suckers with spines growing on either side, but the precise structure and internal anatomical features of the animal were unclear.

In the new study, the research team re-examined the fossils using X-rays and gained further insights into the interior of V. rhodanica. They reconstructed its suckers with high resolution to “dissect” them on screen. These suckers resemble those of modern vampire squids but are larger, more numerous, and closer together. V. rhodanica also had two arms with slightly different sucker and spine structures, which were a bit longer than the other 6 arms.

Based on these characteristics and the streamlined, robust body of V. rhodanica, the research team hypothesized that this creature was an ocean predator, using its specialized arms with super suckers to catch and manipulate prey. This sets it apart from modern vampire squids, which do not hunt but instead feed on small organisms and organic debris that falls from the upper water layers into the deep sea.

Modern vampire squids use long, slender, and sticky filaments to siphon food from the water column, but the research team found no evidence of such filaments in V. rhodanica. Whalen noted that it is possible V. rhodanica did not actually possess such structures, or that the fossil specimens were incomplete. If this ancient creature truly lacked slender filaments, it likely has closer relatives to modern octopuses rather than vampire squids. However, this remains an open question.