Despite facing criticism and suspicion, Andreas Vesalius (1514 – 1564) devoted his entire life to dissecting and studying human anatomy.

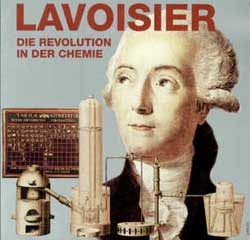

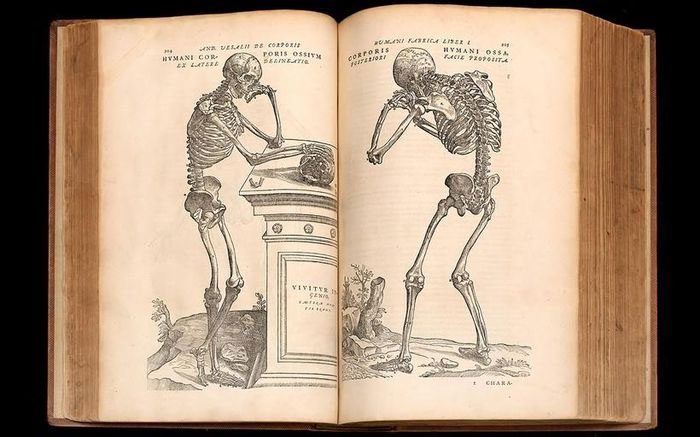

He left behind numerous valuable documents for the field of medicine, particularly a seven-volume series on the structure of the human body.

A page from Vesalius’s series On the Structure of the Human Body. (Image: Wikipedia.org).

The Medical Student… Grave Robber

Vesalius was born in Brussels (Belgium) into a family with a medical tradition. His grandfather was the court physician to Emperor Maximilian, and his father was the court physician to Emperor Charles V. From a young age, Vesalius was destined to become a physician.

Initially, Vesalius was not particularly interested in studying medicine. At 14, he enrolled at the University of Leuven (Belgium), majoring in arts, and at 18, he decided to pursue a military career at the University of Paris (France). However, after reading early anatomical studies by the physician and philosopher Galen (129 – 216, Italy), he changed his mind.

Galen lived in an era when human dissection was prohibited, so he could only dissect ape bodies, which are the closest to humans. For hundreds of years, his writings served as a guide for medicine and were foundational texts for Western physicians.

However, for Vesalius, all of this was unreliable because “the human body is different from the ape’s body.” To prove this, Vesalius… robbed graves, extracting bones from corpses to compare with ape bones. He also assembled a complete skeleton from the remains he had dug up.

War forced Vesalius to leave France and return to Belgium, where he continued his studies at the University of Leuven. In 1536, at the age of 22, Vesalius graduated and was invited to become the head of the surgery and anatomy department at the University of Padua (Italy).

After some time teaching, he decided to become an assistant to the future Pope Paul IV, treating leprosy patients. In 1538, Vesalius published his first anatomical work, officially declaring war on Galen.

Portrait of Andreas Vesalius. (Image: Britannica).

Correcting the “Father of Anatomy”

Unlike Galen, who could only infer human anatomy from animal dissection, Vesalius personally dissected human corpses and frequently demonstrated in front of students. He believed that “seeing is believing” and encouraged students to practice. Starting in 1539, Vesalius gained access to a steady supply of corpses, primarily of executed criminals.

The more he dissected, the more anatomical results Vesalius gathered, gradually “defeating” Galen’s assertions, such as the human sternum not consisting of seven segments but only three, the human mandible being a single bone rather than two, and major blood vessels originating from the heart, not the liver… Ultimately, he refuted and corrected about 300 of Galen’s errors.

In 1543, Vesalius conducted a public dissection of the most notorious criminal in Switzerland, Jakob Karrer von Gebweiler. After completing the dissection, he donated the skeleton to the University of Basel. This skeleton, known as the Basel Skeleton, is regarded as “the oldest existing anatomical skeleton in the world.” It is currently displayed at the Anatomy Museum of the University of Basel.

In addition to dissection, Vesalius commissioned detailed illustrations of his anatomical findings, totaling 273 images, and compiled the results of his research into seven volumes.

Volume 1 focused on bones and cartilage, volume 2 on ligaments and muscles, volume 3 on veins and arteries, volume 4 on nerves, volume 5 on the digestive and reproductive organs, volume 6 on the heart and related organs, and volume 7 on the brain.

Although it was not the first document on anatomy, Vesalius’s content and illustrations were comprehensive and of high quality. Instantly, the series On the Structure of the Human Body became an outstanding and classic medical work. In fact, a series of pirated editions appeared on the market while Vesalius was only 28 years old.

The Resented Court Physician

Behind Vesalius’s journey of penance lies two hypotheses:

- The first hypothesis originates from rumors that he had dissected living humans, which led the Spanish court to discover his actions and punish him by forcing him to go on a pilgrimage.

- The second hypothesis suggests that out of disdain for the court but unable to resign, Vesalius used the pilgrimage as an excuse to escape.

Vesalius’s fame reached the Italian court, and the reigning emperor, Charles V (1500 – 1558), personally invited him to the palace as the court physician. Overjoyed and proud, Vesalius left the University of Padua and declined several other teaching offers, stepping into the royal court while also marrying a beautiful lady from Belgium, Anne van Hamme.

Contrary to the young professor’s enthusiasm, the court was rife with jealousy. Other court physicians looked down on and mocked Vesalius, calling him “the butcher doctor” and “merely a dissector of human corpses.” Disheartened, Vesalius wished to resign but did not dare.

For the next 11 years, he repeatedly requested to go to the battlefield, treating wounded soldiers and continuing his dissections, seeking answers to medical questions and developing medicines. During this time, Vesalius also took an interest in Chinese medicine, expressing skepticism about the efficacy of Chinese herbal remedies.

Seizing the opportunity, other court physicians berated and criticized Vesalius incessantly, demanding that Emperor Charles V punish him. In 1555, one of the court physicians opposing Vesalius, Jacobus Sylvius, even published an article claiming “the structure of the human body has changed since Galen studied it.”

That same year, Vesalius moved to Spain to serve as the court physician for Emperor Philip II (1527 – 1598), and he also took time to edit and republish his series On the Structure of the Human Body.

In 1564, Vesalius set off on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land to atone for having dissected too many corpses. Upon arriving in Jerusalem, he received a letter from the Venetian Senate inviting him to resume his position as a professor at the University of Padua.

On his way back to Italy, Vesalius’s ship encountered a storm and sank. He managed to survive and reached the island of Zakynthos but soon passed away at the age of 49. A benefactor paid for his funeral.