Once serving NASA’s balloon project, the Holmdel horn antenna was repurposed to analyze cosmic radio signals and detect evidence of the Big Bang.

Physicists and astronomers believe that the universe began with the Big Bang – a violent event that occurred about 13 billion years ago, marking the birth of the universe. The Big Bang theory posits that the entire universe was concentrated in an extremely hot and dense state known as a singularity, which then began to rapidly expand, leading to the formation of matter, including atoms and subatomic particles. These atoms later clustered together to form galaxies, stars, and other structures in the universe.

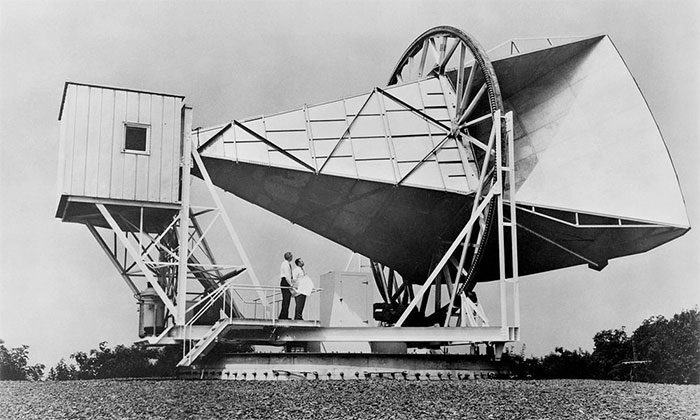

The Holmdel horn antenna is approximately 15 meters long. (Photo: Amusing Planet).

For a long time, the scientific community wondered if a violent event like the Big Bang would leave behind any evidence, a “relic” of radiation in the form of cosmic background noise spread throughout the universe. The Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation was first predicted by American cosmologists Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman in 1948. However, the mainstream astronomical community at that time was not interested in cosmology. The Big Bang theory itself was also controversial. An alternative was the steady state theory, which posited that the universe exists eternally and remains essentially unchanged at any given moment.

In a brief study by Soviet astrophysicists A. G. Doroshkevich and Igor Novikov in the spring of 1964, CMB radiation was first recognized as a detectable phenomenon. That same year, Robert H. Dicke, along with two colleagues at Princeton University, Jim Peebles and David Wilkinson, began preparations to search for this microwave radiation.

This team of astrophysicists believed that the Big Bang not only scattered matter that coalesced into galaxies but also released a vast amount of radiation. If equipped with the right devices, they believed they could detect this radiation, even in microwave form, due to significant redshift (the phenomenon where light from objects moving away from the observer appears redder).

During this time, on Crawford Hill in Holmdel, New Jersey, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were testing a horn antenna (a type of antenna that flares out) designed to map radio signals from the Milky Way. The Holmdel horn antenna was initially constructed as part of the Echo Project aimed at detecting radio waves reflected from large mylar balloons.

The Echo Project was an initiative by NASA, where large mylar balloons over 30 meters in diameter were inflated to approximately 1,600 kilometers above Earth, passively reflecting incoming radio waves off their shiny surfaces. NASA created these simple passive reflector devices to transmit telephone, radio, and TV signals across continents.

The 15-meter Holmdel horn antenna, with an aperture of about 2m2, tapering down to a 20cm output, transmitted radio waves to a receiver. Shortly after the Echo project, the Telstar satellite was launched into space, rendering the Echo system obsolete. This freed the Holmdel horn antenna from previous commercial constraints, allowing it to be used for research purposes.

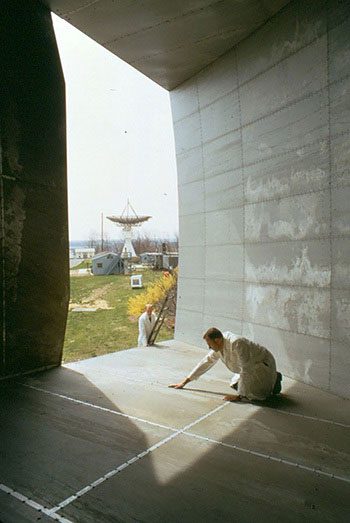

Arno Penzias (right) inspects the inside of the horn antenna with Robert Wilson (left). (Photo: Nokia Bell Labs)

Seizing the opportunity, Penzias and Wilson decided to use the Holmdel horn antenna to analyze radio signals from interstellar space. However, when they began their observations, they encountered a mysterious background noise in the microwave spectrum, seemingly emanating from all directions in the sky. They thoroughly checked the equipment, even cleaning pigeon droppings off the antenna to eliminate potential sources of interference, but the background noise persisted. Penzias and Wilson concluded that it originated from outside the Milky Way but still could not identify which radio source could explain it.

When a professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) informed Penzias about Jim Peebles’ research, Penzias and Wilson began to realize the significance of their findings. Penzias contacted Dicke and invited him to Bell Labs to see the horn antenna and hear the background noise. Dicke concluded that the characteristics of the radiation discovered by Penzias and Wilson matched the radiation predicted by him and his colleagues at Princeton University.

Two brief studies published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters in July 1965 reported these discoveries, first presenting Dicke’s theory and then the observations of Penzias and Wilson. In 1978, Penzias and Wilson were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. In 1989, the Holmdel antenna was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in the United States for helping these two scientists find evidence for the Big Bang theory, forever changing the field of cosmology.