The Bramah lock is a symbol of exceptional security and is claimed to be unpickable even when it has been opened.

Joseph Bramah and the challenge lock with the inscription “Any craftsman who can create a tool to open or pick this lock will immediately receive a reward of 200 Guinea. It took 61 years to successfully pick it. (Photo: Wikipedia Commons).

Bramah began his fascination with locks in 1783 when he was elected as a member of a newly established organization: the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce. […] It is understandable that Bramah chose to attend most of the meetings of the Mechanical branch, and shortly after joining, he gained fame with a simple achievement: picking a lock.

In reality, it was not that simple: in September 1783, a gentleman named Marshall submitted a lock that he claimed was impossible to pick, and a local expert named Truelove fumbled with the lock and a special toolkit for an hour and a half before surrendering. Then, from the back of the audience, Joseph Bramah stepped forward, quickly took out two tools, and opened the lock in just 15 minutes. The auditorium buzzed with excitement: before them was clearly a top-notch mechanic.

The British public at that time was obsessed with locks. An unintended consequence of the social and legal changes sweeping across England at the end of the 18th century was a significant social divide: while the aristocracy had long resided in grand houses protected behind walls, parks, and moats under the watch of servants, the new business class lived in homes that were easily accessible to the poor.

They and their possessions were generally both visible and vulnerable, especially in rapidly developing cities; they primarily lived in houses and on streets that were within sight of a large number of impoverished individuals. They were envied everywhere. Robberies occurred incessantly. Fear permeated the atmosphere. All doors had to be locked. Locks had to be produced and had to be good.

A lock like Mr. Marshall’s, which could be picked in 15 minutes by a skilled person, and perhaps in just 10 minutes by a starving, reckless individual, was clearly not good enough. Joseph Bramah decided to design and create a better lock. He succeeded in 1784, less than a year after picking Marshall’s lock. With this invention, even a thief would have to surrender, even if using a wax key blank, a tool favored by criminals for determining the positions of the levers and pins inside the lock.

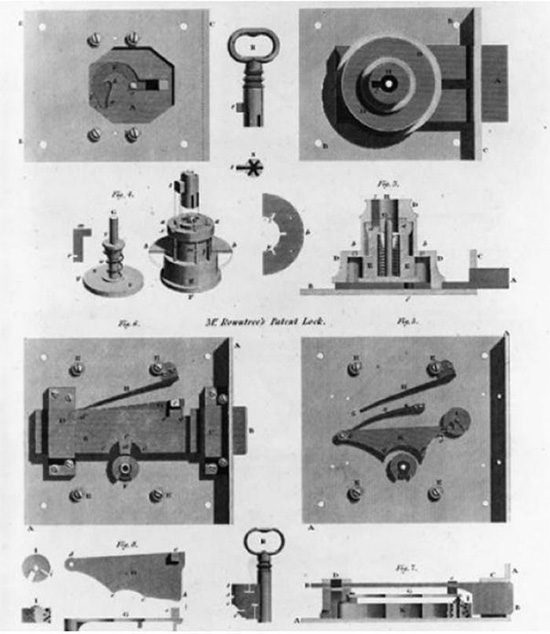

In Bramah’s design, patented in August, the internal levers would rise and fall to new positions when the key was inserted and turned to release the bolt, then return to their original position once the bolt was secured. The result is that the lock is nearly immune to theft, and no matter how much a thief fumbles with a wax key blank, they cannot ascertain the positions of the levers (since they have changed) to release the bolt.

After determining the basic design, Bramah skillfully and ingeniously crafted a complete cylindrical lock, where the levers do not rise and fall due to gravity but move in and out along the radius of the key shaft, following the key’s notches, and then return to their original position thanks to springs, each lever having its own spring. In this way, the entire lock could retract into a small brass cylinder, easily mounted into a tubular recess on a wooden door or safe, with the locking bolt lying flush with the outer edge of the door (when unlocked) or fitting into the brass recess on the door frame (when locked).

Joseph Bramah’s “challenge lock” was first displayed in a shop window in Piccadilly, London.

[…] Thanks to this lock, the name Bramah officially became part of the English vocabulary. Indeed, books still refer to Bramah pen or Bramah lock – the Duke of Wellington praised both inventions, as did Walter Scott and Bernard Shaw.

But the name Bramah, when used alone – as in Dickens’ novels The Pickwick Papers, Sketches by Boz, and The Uncommercial Traveller – indicates that at least with the Victorian public, his name became synonymous with his invention: using (key) Bramah to open (lock) Bramah, a house secured by (lock) Bramah, and handing (key) Bramah to a close friend so they could visit at any hour. It was only when Mr. Chubb and Mr. Yale appeared (first recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1833 and 1869 respectively) that the dominance of the name Bramah was shaken.

[…] One man did manage to pick Joseph Bramah’s lock, which had patiently awaited in the display window of the company at 124 Piccadilly since 1790. This man also participated in the exhibition at the Great Exhibition, was a locksmith, a competitor of Bramah, and an American citizen. He crossed the Atlantic Ocean with the intent of picking all the “unpickable” locks that English engineers could present to him.

He was Alfred C. Hobbs, born in Boston in 1812 to English parents. His burning desire was to prove that American locks were superior to British locks.

[…] Hobbs wrote a formal letter to the Bramah company, requesting an appointment at Piccadilly “regarding the offer written on the sign in the window about picking your lock.” Joseph Bramah had passed away 40 years prior, perhaps until his death, still confident that no one would surpass his challenge. The current management of the company were Bramah’s sons, who received Hobbs’ letter – with some concern over the fateful letter, as they had heard of Hobbs’ reputation. They had no choice but to agree, and a panel of experts was assembled to determine whether the legendary precision lock of 18th century England was truly picked and not broken.

And Hobbs succeeded. He took a total of 51 hours, over the course of 16 days, to raise the lock’s yoke and declare it opened, meaning he had picked it. He used a series of tiny tools designed specifically for lock picking – including a tiny pan-me screw attached to the wooden base on which Joseph Bramah’s lock was placed. (If the lock was placed on an iron base, this tool would have been useless. It was screwed into the wooden base, allowing Hobbs to freely fumble inside the 5 cm long lock while his device held down the 18 tiny levers inside the lock).

He also used a magnifying system where tiny beams of light were reflected inside the lock’s body using special mirrors. He used a tiny brass gauge to determine how deeply each lever was pressed down and employed small hooks to pull the levers that had been pressed too far down. Beside him was a tool tray reminiscent of a surgeon’s tray, minus the scalpel, aimed at a single purpose: to pick the Bramah lock, thereby affirming the superiority of American precision technology.

The Bramah company paid the reward as promised, but they complained that the American’s actions, with dozens of tools and 51 hours of fiddling, were not in the spirit of the challenge. No thief would spend that much time and effort on a lock.

The judges agreed. They pointed out that Hobbs’ approach was unfair, and – although they were aware that the 200 guinea reward had been awarded – they solemnly concluded: “Hobbs, no matter how meticulous, did not tarnish the reputation of the Bramah lock; rather, his effort further affirmed that, in practice, this lock is indeed impregnable.”

The 200 guinea reward then sat proudly in the Crystal Palace for weeks. Alfred Hobbs reveled in his victory, firmly believing that the gold coins were a testament to his achievement. But it was a short-lived victory, and as the judges noted, the fact that the Bramah lock was picked did not negatively impact the company’s business: people were lining up to buy a lock that an expert took 16 days to pick.

The Bramah company still operates in London and sells locks worldwide, all based on the model from 1797 by Joseph Bramah. Meanwhile, the Day & Newell company in New York ceased operations shortly after the Great Exhibition. The parautoptic lock of the company was soon picked as well, and it was picked easily with just a wooden stick. The person who successfully picked that lock was the heir to a new precision lock company, also the founder of a company that now belongs to the largest lock manufacturer in the world today, Linus Yale.