From a stray dog, Laika was chosen to become the first living being to embark on a “suicide mission,” orbiting Earth aboard Sputnik 2 in 1957.

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet spacecraft Sputnik 1 made history by becoming the first artificial object to orbit Earth. Following the success of Sputnik 1, engineers quickly built Sputnik 2 with a pressurized cabin for a dog. The spacecraft, weighing 508 kg, was six times heavier than Sputnik 1, and would carry the first living creature into orbit.

Laika the dog on a stamp from the Emirate of Ajman, now part of the UAE. (Photo: Vintageprintable1/Flickr)

The reason the Soviet Union chose a dog instead of animals from the Hominoidea family is not entirely clear. It is possible that the research of scientist Ivan Pavlov on dog physiology in the late 19th to early 20th century laid the groundwork for their use. Additionally, stray dogs were prevalent on the streets of the Soviet Union, making them easy to find.

Selection Process

Soviet experts began the selection process with female stray dogs, as females are smaller and appeared more docile. Initial tests assessed their obedience and passivity. Those who made it to the final selection lived in small pressurized cabins for several days, followed by weeks.

Doctors also monitored their reactions to changes in air pressure and the loud noises that occurred during the spacecraft’s launch. The dogs were fitted with a sanitation device connected to their pelvic region. The dogs disliked this device, and to avoid using it, some retained waste in their bodies, even after being given laxatives. However, some adapted to it.

Eventually, the team selected Kudryavka (Little Curly) as the primary canine astronaut for Sputnik 2 and Albina (White) as the backup. When introduced to the public via radio, Kudryavka barked. The animal later became known as Laika, derived from the Russian word for “bark.” Laika was a husky-spitz mix, about 3 years old at the time.

Some rumors suggested that Albina performed better than Laika, but because she had just given birth and won the affection of her caretakers, she did not face the suicide mission. Doctors performed surgeries on both dogs, implanting medical devices in their bodies to monitor heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and body movement.

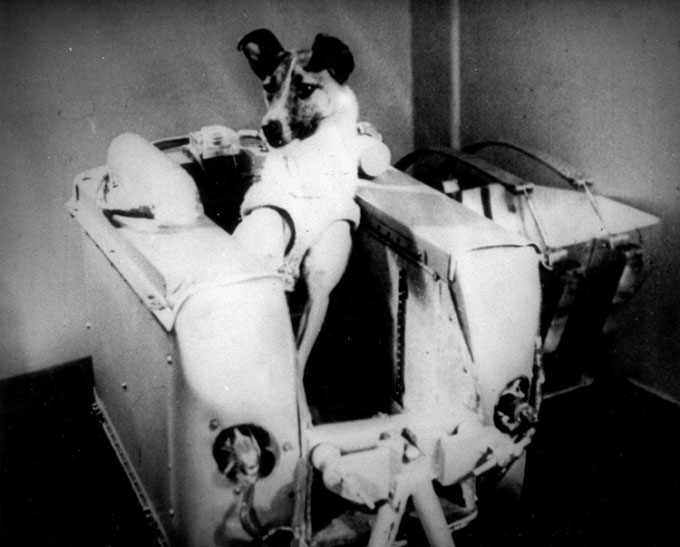

The Sputnik 2 spacecraft carrying astronaut dog Laika launched on November 3, 1957. (Photo: NASM)

The “One-Way” Space Journey

Three days before the launch, Laika entered a restricted area where she could only move a few inches. The animal was bathed, equipped with sensors, a sanitation device, and dressed in a space suit.

At 5:30 AM on November 3, Sputnik 2 lifted off. The noise and pressure of the flight frightened Laika: her heart rate tripled, and her breathing increased fourfold compared to normal. The National Air and Space Museum of the United States still retains documents showing Laika’s respiratory process throughout the flight.

Laika was alive when she reached orbit and circled the Earth for about 103 minutes. Unfortunately, the loss of the thermal shield caused the temperature in the cabin to rise unexpectedly, endangering the animal.

“The internal temperature of the spacecraft after the fourth orbit exceeded 90 degrees. It was truly unrealistic to expect Laika to survive another one or two orbits,” said Cathleen Lewis, who oversees international space programs and spacesuits at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

For Laika, even if all the equipment on board functioned well, and there was enough food, water, and oxygen, she would still die when Sputnik 2 re-entered the atmosphere after about five months, completing 2,570 orbits. However, the flight that promised Laika’s inevitable death provided evidence that space could be habitable.

Laika the dog on a stamp from Romania, issued between 1957 and 1987. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The Impact of Laika

At that time, awareness of animal rights was not as prominent as it is in the early 21st century, but some people protested the intentional letting of Laika die due to the Soviet Union’s lack of technology to safely return her to Earth. However, Lewis believes that using animals for test flights was essential to prepare for human space travel.

“There are things we cannot determine due to limited experience with high-altitude flights. Scientists really did not know how humans would react in space travel, or whether astronauts could continue to function normally,” Lewis said.

Shortly after the flight, the Soviet mint created an enamel pin featuring Laika to commemorate “the first passenger in space.” Some of the Soviet allies at the time, such as Romania, Albania, and Poland, also issued Laika stamps between 1957 and 1987.

During the Mars exploration mission Opportunity in March 2005, NASA informally named a location in a crater on the planet Laika. In 2015, Russia erected a statue in memory of Laika on a rocket at a military research facility in Moscow.

Laika has become a part of history as the first living being to orbit Earth. Today, the story of the “little pioneer” continues to appear on websites, in videos, poetry, and books. In the book Beastly Natures: Animals, Humans and the Study of History, expert Amy Nelson shares that the Soviet Union turned Laika into a “timeless symbol of sacrifice and human achievement.”