In our perception, pigs are quite slow and somewhat “dim-witted,” and their meat can be processed into many delicious dishes. However, their ancestors were incredibly fierce fighters.

We often think of pigs as eating and sleeping, then, upon reaching a certain size, heading straight to the slaughterhouse to end their short lives. After that, they are transformed into sausages, hams, bacon, and more.

However, despite appearing lazy and foolish, they actually possess remarkable fighting abilities. A look into the evolutionary history of pigs reveals that some extremely aggressive species have emerged in the lineage of this animal.

Pigs’ subfamily.

Examining the evolutionary tree of pigs shows that it is relatively “poor,” as we commonly refer to members of the pig family simply as pigs, given their similar appearance, snouts, ears, and the males often have long tusks.

Currently, there are only two families in the Suina suborder (the pig suborder): one is Suidae (the pig family), and the other is Pecari (the peccary family), which, despite resembling pigs, are not considered true pigs.

There are 22 species within the entire Suidae subfamily. Before being introduced by humans to various parts of the world, pigs mainly inhabited Asia, Europe, and Africa, while peccaries were found in the Americas.

Pigs appear lazy and foolish, but they have remarkable fighting abilities.

During the Eocene to Oligocene epochs, the Suina suborder was quite successful as they played the role of predators for a time. Historically, the pig suborder was divided into the Suina suborder, the Ancodonta suborder, and the Paleodonta suborder; our current pigs belong to the Suina suborder, while the other two branches are completely extinct.

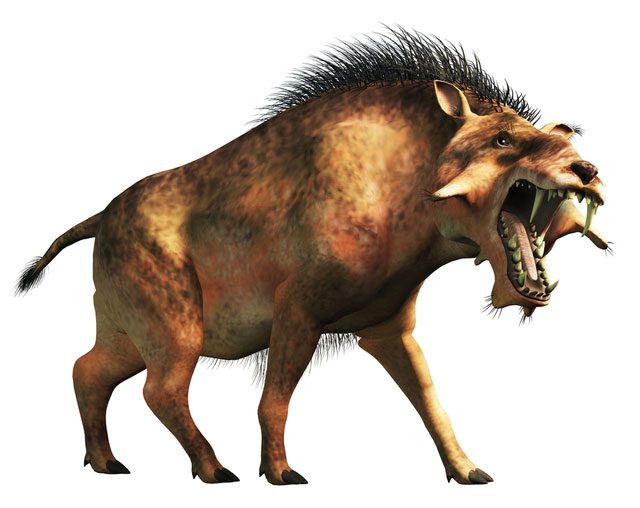

About 40 million years ago, the ancestors of pigs first appeared in Europe. Subsequently, the pig subfamily branched out. Around 37 million years ago, gigantic pigs emerged, with the most famous member being Dinohyus hollandi.

The giant pig species Dinohyus hollandi emerged 37 million years ago.

By the Oligocene epoch, pigs of the Suina suborder had expanded their habitats across Eurasia, Africa, and America. Paleontologists have discovered that many herbivorous animals from the Oligocene show tooth marks on bones that do not resemble traditional carnivore bites. Later comparisons revealed that these marks belonged to the species Entelodon, which relied on their immense bite force and size to become powerful predators.

Similar to modern wild boars, adult males of this species had long tusks, but rather than extending outward, these tusks evolved into shapes resembling those of other predatory mammals, increasing their lethality.

They could open their mouths 108 degrees, the largest angle among known animal species.

Besides Entelodon, Daeodon is also noted for having a fearsome jaw structure, often mentioned by paleontology enthusiasts. These creatures were larger than cattle and would eat anything they could find; they would even steal food from contemporary carnivores and, if food was scarce, would not hesitate to consume carrion.

Members of the giant pig family had massive muscles and extraordinary fighting abilities, and they were also ruthless towards their own kind, especially during breeding seasons.

Perhaps the only thing that limited pigs from rising to the top of the food chain is that they lack sharp claws and can only rely on their mouths. Unfortunately, the climatic changes of the Oligocene epoch severely impacted the pig subfamily, leading to the extinction of many species.

Later, the species within the Suidae and Pecari families continued to thrive, occupying ecological niches left by the previously extinct pig species.

Daeodon is also known for its fearsome jaw structure.

Modern pigs have the strongest sense of smell among mammals and can detect the scent of insects, seeds, and grass roots buried deep in the ground, which helps them survive during the Oligocene extinction.

Regarding their eating habits, they have inherited the carnivorous tendencies of their giant pig ancestors, but they also consume plant matter to adapt to various circumstances. The pig family has “borrowed” reproductive methods from rodents, becoming one of the most prolific species among large mammals.

Generally, larger animals tend to have fewer offspring per litter; for example, cattle, horses, deer, and even smaller sheep typically give birth to only one offspring at a time. But pigs are different; a mother pig can give birth to up to 23 piglets in one litter, and they usually have more than 10 piglets at a time.

This is because pigs can shed many eggs simultaneously, often more than 20, and most of them will be fertilized and develop into embryos. The gestation period for pigs is quite short relative to their size, lasting only 110-120 days.

If there is enough food, pigs can give birth 2 to 3 times a year, with piglets needing to nurse for about 2 months before they directly follow their mother in search of food.

Pigs also possess a fairly intelligent brain; among animals, pigs have a high IQ, even higher than that of dogs and cats. They can look into a mirror and recognize that the reflection is themselves.

Pigs can recognize their reflection in the mirror.

The pigs we see as lazy, chubby, and clumsy are not their true nature; rather, it is because humans need them to be this way.

Pigs on farms typically only grow to near adulthood, and castrated males are left as breeding stock, so the pigs we generally see are mostly immature.

Moreover, due to the cramped spaces in pigsties, pigs do not exercise much, and since they are constantly fed, their size increases due to fat.

Although pigs have degenerated in the confined environment of human captivity and today are often associated with laziness and foolishness, the fighting spirit in their blood has never faded. Experiments have shown that when domestic pigs are released back into the wild, they seem to immediately regain the wild instincts of their ancestors.

Pigs have a strong territorial awareness, and in essence, their temperament has never been fully domesticated by humans; they do not attack people because they are full and do not wish to move. If starved, even domesticated pigs can attack and potentially injure or kill humans.