Behind the Strange Behaviors of Animals Lies a Natural Selection Pressure for Evolution.

Whenever an opossum feels threatened, it plays dead. The opossum rolls over on the ground, curling up in a fetal position. It opens its eyes wide, gapes its mouth, and sticks out its tongue. The only task left is to remain motionless, unresponsive to anything happening in the world around it.

During this time, a more subtle process of death-like state occurs within the opossum’s body. Its body temperature drops, and both its breathing and heart rate decrease significantly. The opossum’s tongue, which is usually a light pink, turns a shade of bluish-green.

The sphincter muscles in its urinary and anal tracts relax, expelling urine and feces from its anus to amplify a foul odor. At this point, just by looking from a distance where the stench prevents you from approaching the opossum, it truly appears to be a dead body.

However, inside that façade, the opossum is still wide-eyed and patiently waiting.

All its senses remain alert to perceive the surrounding environment, directed towards a coyote scavenging for food. It turns out that the presence of this coyote is precisely the reason the opossum has played dead.

The characteristic of the coyote is that it only eats fresh meat and never touches decayed corpses. The opossum’s act has ultimately fooled the predator. Once the coyote moves far away, the opossum begins to stir, tidies itself up, and resumes its daily activities.

Once again, the play-dead strategy has proven effective.

Are Animals Aware of Death?

Despite the dramatic performance, no one can know from the opossum’s perspective whether it truly intends to play dead. If the opossum has no concept of death, its behavior might just be an automatic instinct. Who knows, in its mind, the opossum may simply be rolling over and pretending to be a rock.

While this assumption might be true, we have been mistaken in underestimating the awareness of death in animal species. In fact, this little performance of the opossum is one of the best pieces of evidence scientists have regarding the concept of death within the brains of mammals.

You can induce a chicken into a state of muscle rigidity by drawing a straight line in front of it.

For the second purpose, thanatosis aims to resist the subjugation of predators. Imagine an opossum trying to escape from a coyote; rolling over and playing dead is a better strategy than attempting to run and realizing its speed is not enough to outrun the coyote.

At this point, the coyote might tear into it to subjugate the opossum. This poses a greater risk of leaving a significant wound compared to lying still and pretending to be dead. Some predators tend to treat their prey relatively gently, even releasing and playing with them before delivering the final blow.

Some may remember the location of the dead animal and continue hunting other animals before returning to collect them. Therefore, the thanatosis strategy is beneficial in these situations. The prey can preserve the integrity of their bodies while also hiding or escaping when the predator is not paying attention.

Under the Hand of Evolution

We return to the minimal definition of death that an animal can perceive: inactivity and irreversibility. When a predator sees prey in a state of thanatosis, it may mistakenly believe that the prey is dead based on:

Silence, reduced physiological function, lack of response, and similar behaviors create an illusion of the absence of vital body functions. This means the animal is indeed inactive.

Meanwhile, blood, foul odors, a green tongue, and other signs indicate that this inactivity cannot be reversed, unlike what we might find in a person who is sleeping or unconscious. This means that the animal is dead, and it is dead permanently.

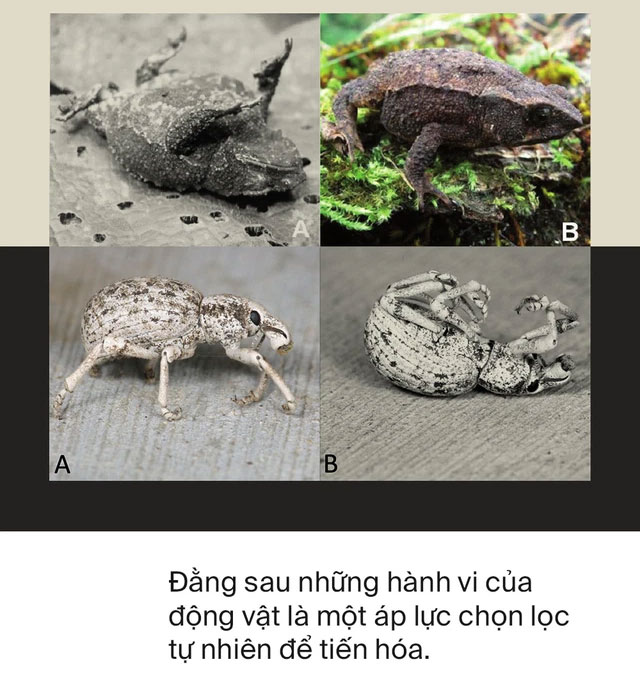

Behind many behaviors exhibited by animals, there must be at least one pressure of natural selection, which facilitates their evolutionary process. Sometimes, these selection pressures lie in how their predators perceive the outside world. This, in turn, determines the chances of whether a prey can survive long enough to pass on its genes.

So here, it could be that the opossums themselves do not know they are playing dead. The very ability of their predators, such as coyotes, to recognize death is the selective pressure that drives the opossum’s thanatosis behavior.

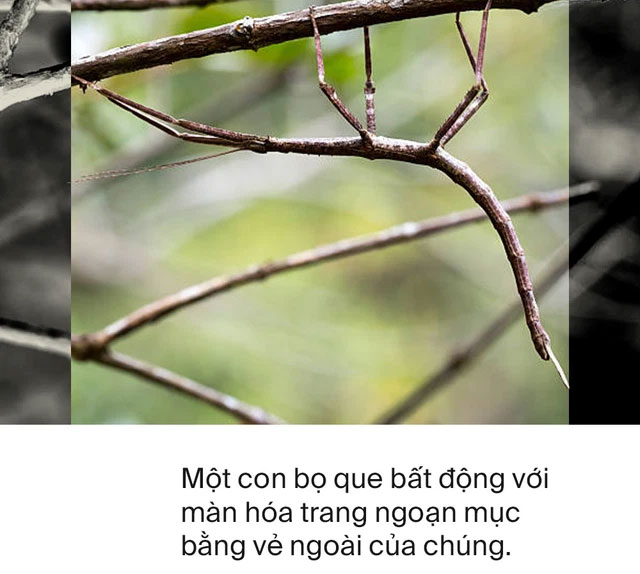

Stick insects are similar; they do not need to look in a mirror to know that they resemble a twig. They simply need to heed the ancestral instinct to stand still when encountering a predator. Subsequently, the appearance passed down from their ancestors will help the stick insect survive.

However, if stick insects have evolved to possess the appearance and instinct of muscle rigidity, then their predators must have also developed a misconception that these insects are real twigs, and they do not want to eat a dry branch.

Throughout their evolutionary history, the ancestors of these twig-like insects would have faced less risk of being eaten by enemies. Thus, the more they resemble twigs, the greater their reproductive opportunities. Ultimately, the genes that express twig-like appearances will be passed down to all their descendants.

Returning to the masters of thanatosis in the animal kingdom, regardless of the specific evolutionary history that has given rise to this behavior, it opens a window for us to glimpse into the minds of predators.

Thanatosis shows us that for whatever reason, predators do not want to eat animals that they think are dead. Throughout their evolutionary history, opossums that can mimic dead bodies more closely will have a higher chance of survival. Thus, when they reproduce, their acting genes will also be passed down to the next generation.

Therefore, any explanation regarding the protective function of thanatosis will lead to one conclusion: that animals have the ability to recognize death, if not the opossums themselves, then the coyotes hunting them.

Besides thanatosis, there are other reasons that show that carnivores understand what death is. They have a strong mental motivation to pay attention to the moment a prey dies. In that hunt, the death of the prey represents two extremes:

One is that it has become edible food; the other is that it is no longer alive to pose a danger (as many animals are equipped with sharp horns or hooves, or will react violently to a predator’s attempts to subdue them).

Throughout the life of a predator, it has witnessed hundreds, if not thousands, of prey deaths to understand what irreversible inactivity is and the basic characteristics of death.

In summary, the concept of death is not just a unique achievement of humanity. It may be a fairly common trait in the animal kingdom. We humans often think of ourselves as a unique species, but now is the time to rethink that.

The exceptionalism of humanity is what separates us from nature, allowing us to exploit it for our own benefit. Once we eliminate that mindset, we can develop a sense of protecting nature and respecting the habitats of other animal species.