Using CT scanning techniques on 16th-century books, researchers discovered pieces of parchment taken from earlier manuscripts.

Even in the Middle Ages, recycling became popular: scraps of parchment from older manuscripts were often repurposed for other books. Using Computed Tomography (CT) scanning, a group of researchers demonstrated that it is possible to see the remnants from the Middle Ages hidden beneath the covers of certain books.

The Secrets Hidden Beneath Book Covers

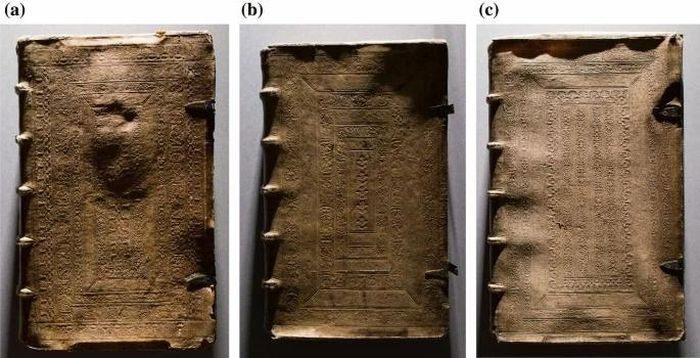

The Historia Animalium, bound in pigskin, was subjected to CT scanning. (Photo: Emma Guerard).

Studying these medieval cover scraps could help reveal how, when, and where the first books were assembled, while also potentially uncovering previously unknown manuscripts.

In Europe, books were copied by hand until the mid-15th century. Known as manuscripts, these written records were often true works of art, featuring multiple ink colors on carefully prepared sheets of calf, goat, or sheep skin.

However, with the advent of the printing press in Europe around 1450, the need for such manuscripts diminished. Yet some bookbinders chose to reuse parchment pages.

Eric Ensley, the rare books and maps curator at the University of Iowa, stated: “They could use older, sturdier manuscripts to help reinforce the structure of a new printed book.”

Bookbinders would cut pieces of parchment—sometimes whole pages, other times just thin strips—and paste them into places such as the spine of the book. The book would then be covered, and most of this parchment would be hidden from view.

A Library Hidden Within a Library

Joris Dik, a materials scientist researching bonding fragments at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the recent research, remarked: “There is actually a whole library within a library in the form of these fragments.”

In recent decades, researchers have begun examining beneath book covers using non-invasive techniques to find medieval book fragments and read what is written on them.

However, those techniques have limitations, prompting Dr. Ensley and his colleagues to try CT scanning, a method available in hospitals.

This three-dimensional imaging technique addresses focus issues that other methods struggle with. The scanning process can be completed in seconds instead of hours as before.

Two scientists stand on either side of the arch of the CT scanner as three large brown books are fed into it. (Photo: Eric Ensley).

A trio of Historia Animalium books, an encyclopedia of animals printed in the 16th century, was retrieved from the archives of the University of Iowa and scanned using the university’s medical scanner.

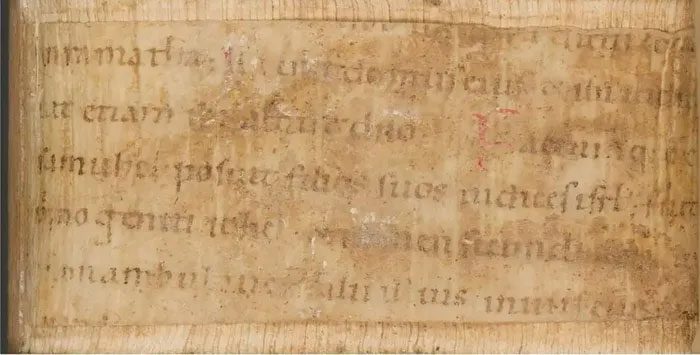

The researchers found a book with a damaged cover that could be peeled back to reveal medieval parchment scraps—featuring red and black ink—on the spine of the book.

Under the supervision of Giselle Simon, a curator at the University of Iowa Library, the research team placed three books on the bed of the CT scanner in Eric Hoffman’s lab at the Carver College of Medicine. The books fit into the space, and scanning all three took less than a minute.

Together with Dr. Tachau, Dr. Ensley viewed the hidden text of some of the revealed fragments on the scanner’s screen.

He said: “We both leaned in and started reading Latin together. It was a goosebump moment.”

Many fragments found in the scans came from a handmade Latin Bible centuries before the printed books were used in the experiment. (Photo: Eric Ensley).

Many medieval fragments in Historia Animalium originated from a Latin Bible dating back to the 11th or 12th century, the research team reported in April in the journal Heritage Science.

The individual pieces discovered by the team will eventually be digitized in Fragmentarium, an online repository containing over 4,500 medieval fragments. William Duba, a historian at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, who coordinates Fragmentarium, stated that the repository serves as a means to disseminate information contained in these hidden historical fragments.

He said: “The book spines are hiding treasures.”