During development, oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) play a crucial role in shaping the nervous system and brain.

As a child’s brain enters its developmental phase, it generates numerous connections. Some of these connections, or synapses, transmit important signals as the child interacts with their environment. The remaining connections will be pruned away as the brain matures, retaining only those necessary for understanding and engaging with the world.

Recently, Professor Lucas Cheadle and colleagues from the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) discovered the cells involved in this shaping process. These cells, known as oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), are essential for forming a healthy brain during early development.

According to research published in the journal Nature Neuroscience on September 28, this discovery contributes valuable insights into brain development, potentially leading to new strategies for treating neurological disorders such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). This finding also paves the way for using high-powered microscopy to examine the brains of adult mice.

The authors hypothesize that these cells may be busy eliminating synapses that the brain does not need. Professor Cheadle questions whether OPCs perform a similar function in the brains of young children. This is crucial because experiences during brain formation and development significantly impact the establishment of neural circuits.

The researchers raised young mice in darkness. When they were first exposed to light, the OPCs began to engulf the synapses in response. The OPCs appear ready to adjust brain connections based on experience. These cells are highly responsive to new experiences, capable of taking in that information and using it to form brain connections.

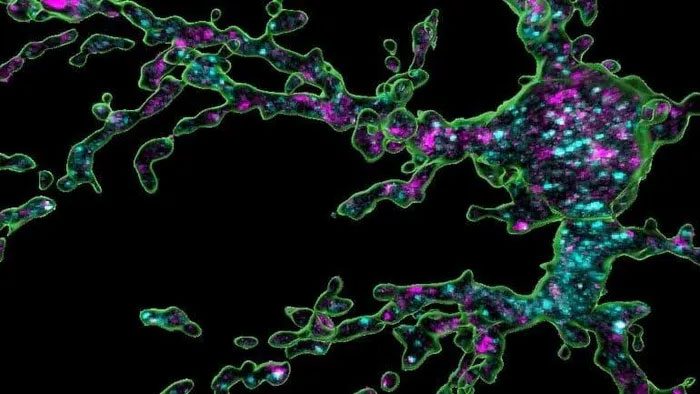

OPC cells (in green) help the brain adjust neural circuits as children and young animals develop. (Photo: Cheadle lab/Imaris software/CSHL).

This discovery highlights the surprising role of OPCs. Some types of cells assist in forming neural circuits by eliminating unnecessary connections. Previously, OPCs were primarily known for their function in producing myelin and supporting neurons.

According to Professor Cheadle, these cells act as intermediaries between what is happening in the external world and what is occurring within our brains. He hopes this discovery will enhance our understanding of neurodevelopmental disorders. He plans to investigate whether faulty shaping and pruning of OPCs play a role in conditions such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder.