Whooping cough (pertussis) is a highly contagious disease caused by a bacterium called Bordetella pertussis. This bacterium attaches to the tiny, hair-like projections lining a part of the upper respiratory tract. It releases toxins that damage these projections and cause inflammation (swelling).

Transmission

Whooping cough is extremely contagious, and it is only found in humans, spreading from person to person. Individuals infected with whooping cough typically transmit the disease when they cough or sneeze while in close contact with others, who then inhale the bacteria. Many infants contract whooping cough from siblings, parents, or caregivers who may not even realize they are infected. Symptoms usually appear within 5 to 7 days after exposure, although sometimes they may not manifest for up to 3 weeks.

While the whooping cough vaccine is the most effective tool we have to prevent this disease, no vaccine provides 100% effectiveness. If whooping cough is circulating in the community, there is a high likelihood that a fully vaccinated person of any age can still contract this highly contagious disease. If you or your child has a cold that includes a persistent cough lasting for an extended period, it may be whooping cough. The best way to be certain is to consult a doctor.

Microscopic image of Bordetella pertussis bacteria using Gram staining technique. (Photo: CDC).

Signs and Symptoms

Whooping cough can cause severe illness in infants, children, and adults. The disease often begins with cold-like symptoms and may include a mild cough or low-grade fever. After 1 to 2 weeks, more severe coughing begins. Unlike a cold, whooping cough can present a series of continuous coughing fits that last for weeks.

In infants, coughing may be minimal or even absent. Infants may exhibit a symptom known as “apnea.” Apnea is a temporary cessation of breathing. Whooping cough is most dangerous for young children. Half of infants under 1 year old with whooping cough are hospitalized.

Whooping cough can cause intense coughing, resulting in rapid, severe bouts of coughing until air is expelled from the lungs, leading to a loud wheezing sound when breathing in. Severe coughing can cause vomiting and extreme fatigue. Typically, wheezing is absent, and infections are often milder (less severe) in teenagers and adults, especially those who have been vaccinated.

Early symptoms may last for 1 to 2 weeks and typically include:

- Runny nose.

- Low-grade fever (often mild throughout the illness).

- Mild or intermittent cough.

- Apnea – temporary cessation of breathing (in infants).

Because early whooping cough symptoms often resemble those of a common cold, it is frequently overlooked and diagnosed only when more severe symptoms appear. Infected individuals are most contagious about 2 weeks after the onset of coughing. Antibiotics can reduce the period of contagiousness.

As the disease progresses, the classic symptoms of whooping cough appear, including:

- Multiple rapid coughing fits followed by a high-pitched wheezing sound.

- Vomiting.

- Extreme fatigue after each coughing episode.

Progression of Whooping Cough

Coughing fits may persist for at least 10 weeks. In China, whooping cough is referred to as “the 100-day cough.”

Although individuals often feel exhausted after each coughing fit, they may appear relatively well between episodes. Coughing tends to become more frequent and severe as the illness progresses, often worsening at night. The disease may be milder (less severe) and without the typical wheezing in vaccinated children, teenagers, and adults.

Recovery from whooping cough can be slow. Coughing may lessen in severity and frequency. However, coughing fits may return due to respiratory infections months after recovering from whooping cough.

Complications

Infants and Children

Whooping cough can lead to severe complications and sometimes life-threatening situations in infants and young children, especially those who are not fully vaccinated.

About half of infants under 1 year old diagnosed with whooping cough require hospitalization. The younger the child, the more likely they are to need hospital treatment. Among infants hospitalized for whooping cough:

- 1 in 4 (23%) will develop pneumonia (lung infection).

- 1 or 2 in 100 (1.6%) will experience seizures (violent shaking, difficult to control).

- 2/3 (67%) will have apnea (slow or halted breathing).

- 1 in 300 (0.4%) will develop encephalopathy.

- 1 or 2 in 100 (1.6%) may die.

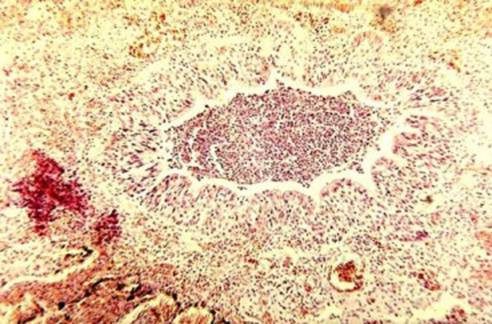

Bronchiolitis in infants with pneumonia due to whooping cough. (Photo: CDC).

Teenagers and Adults

Teenagers and adults can also experience complications from whooping cough. Complications are generally less severe in these age groups, particularly among those who have been vaccinated. Complications in teenagers and adults are often caused by the coughing fits themselves. For example, individuals may faint or sustain rib fractures during severe coughing episodes. In one study, less than 5% of teenagers and adults with whooping cough were hospitalized. Pneumonia was diagnosed in 2% of this patient group. The most common complications in another study of adults with whooping cough included:

- Weight loss (33%).

- Loss of bladder control (28%).

- Fainting (6%).

- Rib fractures due to severe coughing (4%).

A child with burst blood vessels in the eyes and bruising on the face due to excessive coughing from whooping cough. (Photo: CDC).

Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosis

Whooping cough can be diagnosed by considering if the individual has been exposed to whooping cough and through the following examination methods:

- Medical history/development of typical signs and symptoms.

- Physical examination.

- Tests including swabbing the back of the throat.

- Blood tests.

Treatment

Whooping cough is typically treated with antibiotics, and early treatment is crucial. Treatment can make the infection less severe if it begins early, before coughing fits develop. It also helps prevent transmission to close contacts (those who have spent significant time around the infected individual). Treatment after 3 weeks of illness is nearly ineffective because the bacteria have disappeared from the individual’s body, even if symptoms persist. This is because the bacteria have already caused damage to the individual’s body.

There are several antibiotics used to treat whooping cough. If you or your child is diagnosed with whooping cough, your doctor will explain how to treat the infection. There will be a separate article on antibiotic treatment recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for whooping cough.

Whooping cough can sometimes be very serious and may require hospitalization. Infants are at the highest risk of severe complications due to whooping cough. See some images of infants being treated for whooping cough in the hospital.

An infant being treated for severe whooping cough. (Photo: CDC).

If your child is being treated for whooping cough at home

Do not give cough medicine unless directed by a doctor. Cough medicine may not help and is generally not recommended for children under 4 years of age.

Manage whooping cough and reduce the risk of spreading it to others by:

- Following the prescribed antibiotic regimen.

- Keeping the home free of irritants as much as possible, as these can trigger coughing, such as tobacco smoke, dust, and chemical fumes.

- Using a clean, cool mist humidifier to help loosen mucus and soothe coughing.

- Practicing good hand hygiene.

- Drinking plenty of fluids, including water, juice, and soup, and eating a lot of fruits to prevent dehydration. Contact the doctor immediately if any signs of dehydration are noticed. Signs of dehydration include dry and sticky mouth, drowsiness or fatigue, excessive thirst, infrequent urination or fewer wet diapers, no tears when crying, muscle weakness, headache, dizziness, or lightheadedness.

- Eating small, frequent meals to help prevent vomiting if it occurs.

If your child is being treated for whooping cough in the hospital

Your child may need help keeping their airways clear, which might require suctioning thick respiratory secretions. Close monitoring of breathing and oxygen may be necessary. IV fluids might be needed if your child shows signs of dehydration or poor appetite. Preventative measures, such as practicing good hand hygiene and keeping surfaces clean, should be strictly followed.

Prevention

Vaccines

The best way to prevent whooping cough in infants, children, teenagers, and adults is vaccination. Additionally, keeping infants and individuals at high risk of complications from whooping cough away from those infected is essential.

In the United States, the whooping cough vaccine recommended for infants and children is called DTaP. This combination vaccine protects against three diseases: diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough. Currently, in Vietnam, the vaccine used to prevent whooping cough is Quinvaxem.

The protection offered by the vaccine against these three diseases diminishes over time. Before 2005, only a booster vaccine (Td) protecting against two diseases, tetanus and diphtheria, was available and was recommended for teenagers and adults every 10 years. Today, there is a booster vaccine for older children, teenagers, and adults that protects against three diseases: tetanus, diphtheria, and whooping cough (Tdap).

The easiest thing for adults to do is to get the Tdap vaccine instead of the regular Td booster against tetanus they plan to receive every 10 years. The Tdap dose can be given earlier than the 10-year mark, making it a good idea for adults to talk to their healthcare provider about what is best for their particular situation.

Infection

If a doctor determines that your child/you have whooping cough, your child/you will have natural (immunity) protection against future infections. Some observational studies indicate that whooping cough can provide immunity for 4 to 20 years. Since this immunity decreases over time and does not provide lifelong protection, regular preventive vaccinations are recommended.

Antibiotics

Infants under 12 months are at higher risk of serious complications from whooping cough.

If you or a family member is diagnosed with whooping cough, a doctor or local healthcare facility may recommend preventive antibiotics (medications that can help prevent bacterial infections) for other family members to stop the spread of the disease. Additionally, others outside the family who have been in contact with the infected person may receive preventive antibiotics depending on whether they are considered at risk of serious illness or if they have frequent contact with someone deemed at high risk for severe disease. There will be a separate article on the use of preventive antibiotics for whooping cough after exposure.

Infants under 12 months are at higher risk of serious complications from whooping cough. Although pregnant women do not have an increased risk for severe illness, those in their third trimester are considered at increased risk because they may expose their newborns to whooping cough. You should discuss whether you need preventive antibiotics with your doctor, especially if there are infants or pregnant women in your family or if you plan to be in contact with an infant or a pregnant woman.

Hygiene

Like many respiratory illnesses, whooping cough spreads through coughing and sneezing when close contact occurs, leading others to inhale the whooping cough bacteria. Good hygiene practices are always recommended to prevent the spread of this respiratory illness:

- Cover your mouth and nose with a tissue when coughing or sneezing.

- Dispose of used tissues in the trash.

- If you don’t have a tissue, cough or sneeze into your upper sleeve or elbow, not into your hands.

- Wash your hands frequently with soap and water for at least 20 seconds.

- If soap and water are not available, use hand sanitizer.