On Monday (September 19), the biotechnology company Sinogene, based in Beijing, revealed a cloned female Arctic wolf named Maya, marking 100 days since her birth in the laboratory on June 10.

Maya, a brown-gray puppy with a bushy tail, is reported to be healthy, according to Sinogene Biotechnology. During a press conference, the company showcased a video of Maya playing and resting.

Chinese media quoted Mi Jidong, the CEO of Sinogene, stating: “After two years of hard work, the Arctic wolf has been successfully cloned. This is the first case of its kind in the world.”

The Arctic wolf, also known as the white wolf, is a subspecies of the gray wolf native to the Arctic tundra, specifically in the northern Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The conservation status of the Arctic wolf—an indicator used to determine how close a species is to extinction—is considered to be low risk, as this species’ habitat in the Arctic is nearly free from hunters, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

However, climate change increasingly threatens the food supply of Arctic wolves, while human development of roads and pipelines encroaches upon the territory of this wildlife species.

Arctic wolf at Harbin Polarland in China on November 22, 2017. (Photo: Getty Images).

Cloning Technique Similar to That Used for Dolly the Sheep

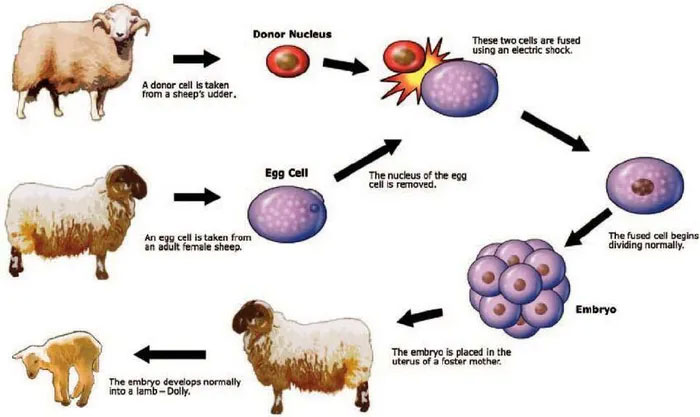

Sinogene launched its Arctic wolf cloning project in 2020, in collaboration with Harbin Polarland amusement park in Harbin (the capital of Heilongjiang Province, China), as stated by the company on the social media platform Weibo. To create Maya, the company employed a process called somatic cell nuclear transfer—the same technique used to create the first cloned mammal, Dolly the sheep, in 1996.

Dolly, the sheep who lived from 1996 to 2003, was the first clone of an adult mammal, created by British developmental biologist Ian Wilmut and colleagues at the Roslin Institute in Scotland. (Photo: Britannica).

Initially, they used skin samples from the original Arctic wolf—also named Maya, imported from Canada to Harbin Polarland—to obtain “donor cells.” These cells were then injected into the eggs of a female dog, which was used as a surrogate.

The scientists created 85 such embryos, transferring them into the wombs of seven small hound dogs (a type of rabbit-hunting dog), resulting in the birth of a healthy Arctic wolf, which is Maya the clone. Sinogene announced on Weibo that a second cloned Arctic wolf is expected to be born soon.

He Zhenming, Director of the Experimental Animal Resources Institute under the National Food and Drug Administration of China, stated that Maya’s successful cloning is a “landmark event of great significance for wildlife conservation worldwide and for the restoration of endangered species.”

The method used to clone Dolly the sheep. (Source: Research Gate).

Sinogene announced that the company will begin collaborating with the Beijing Wildlife Park to further research cloning applications and technology, as well as conduct studies on conservation and breeding of rare and endangered species in China.

The original wolf Maya died of old age in 2021, according to the Chinese newspaper Global Times. The cloned Maya is currently living with her surrogate mother, a hound dog, and will later be transferred to Harbin Polarland, where she will be open to the public.

A hound breed commonly kept for hunting rabbits or as pets. (Photo: Bubbly Pet).

Extinction Crisis

This is not the first time cloning technology has been used by conservation scientists. In Malaysia, where all Sumatran rhinos have died, scientists hope to use frozen tissues and cells to produce new rhinos using surrogate mothers.

In late 2020, American scientists successfully cloned a wild black-footed ferret, a species once thought to be extinct globally.

Other scientists are betting on gene-editing technology. A team in Australia is attempting to edit cells from a marsupial to recreate its close relative, the extinct Tasmanian tiger.

Sumatran rhino in a protected area in Malaysia, October 2013. (Photo: Getty Images).

These efforts are increasing as scientists around the world race to save endangered species, as Earth approaches what many consider the sixth mass extinction. There have been five mass extinction events in history, each wiping out 70-95% of plant, animal, and microbial species.

The most recent occurred 66 million years ago, when the dinosaurs vanished. This sixth mass extinction will be distinct in that it is driven by humans. Humans have wiped out hundreds of species through wildlife trafficking, pollution, habitat loss, and the use of toxic substances.

A 2020 study indicated that about one-third of plant and animal species could face extinction risk by 2070. And things could worsen if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise rapidly.

However, many new conservation efforts are also controversial, raising ethical questions and concerns about the health implications of cloning and gene editing. In the case of Maya, a scientist told Global Times that further research is needed to determine whether cloning could pose potential health risks. More guidelines are also needed to determine appropriate use of the technology, such as cloning only species that are extinct or critically endangered.