June 25 marked a “new first” in the history of space travel. China’s robotic spacecraft, Chang’e 6, has successfully returned rock samples from a location known as “South Pole–Aitken Basin” on the Moon to Earth.

Specifically, according to the China National Space Administration (CNSA), after landing on the far side of the Moon, at the southern edge of the Apollo lunar crater, Chang’e 6 brought back approximately 1.9 kilograms of soil and rock.

The South Pole of the Moon is also where plans are laid to establish the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), led by China, in the future. This project involves partners including Russia, Venezuela, South Africa, and Egypt, with an international agency coordinating the project.

China has a strategic plan to build a space economy and is becoming a world leader in this field. They intend to explore and mine minerals from asteroids and celestial bodies like the Moon, as well as utilize ice and any other useful space resources available in our solar system.

China aims to explore the Moon first, followed by asteroids known as “Near-Earth Objects” (NEO). Next, they plan to move on to Mars, the asteroids between Mars and Jupiter (known as the main belt asteroids), and the moons of Jupiter, using stable gravitational points in space known as Lagrange points for space stations.

Chang’e and Artemis in Competition?

One of China’s next steps in this strategy, the Chang’e 7 robotic mission, is scheduled for launch into space in 2026. This mission is expected to land on the sunlit rim of the Shackleton lunar crater, very close to the Moon’s south pole.

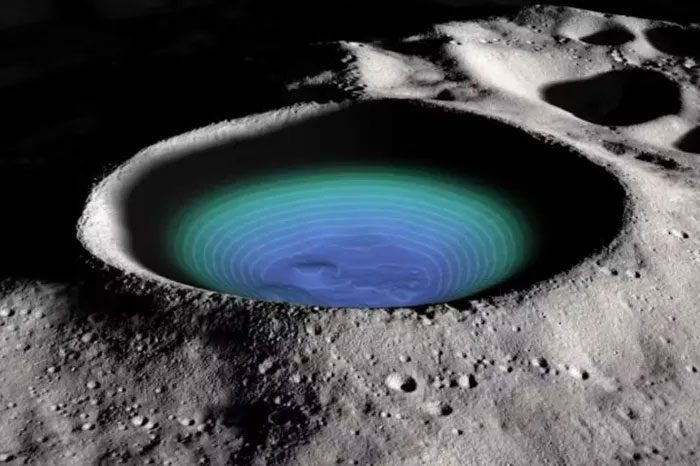

Simulation image of the Shackleton crater at the Moon’s south pole. (Photo: NASA Scientific Visualization Studio)

This landing site is particularly attractive due to its brightness and the accessibility it offers for exploration devices to enter the crater. These dark craters contain large reserves of ice, which could be used for drinking water, oxygen, and rocket fuel—making them indispensable for the construction and operation of the ILRS.

China’s move is considered bold, especially as the United States also aims to establish bases at the Moon’s south pole, with Shackleton crater being a key site. According to plans, a subsequent Chinese mission, Chang’e 8 (earliest launch in 2028), also aims to mine ice and other resources, and to find ways to prove that these resources can support human bases.

Both Chang’e 7 and 8 are viewed as part of the ILRS, and if successful, these programs will set the stage for China’s impressive exploration plans.

Meanwhile, NASA is currently seeking additional partners for an international agreement known as the Artemis Accords, introduced in 2020. The agreements outline how to utilize resources on the Moon, and to date, 43 countries have signed the accords.

However, the U.S. Artemis program, with the goal of returning humans to the Moon this decade, has faced delays due to technical issues.

Delays in any complex new space program are common. However, the next mission, Artemis II, which aims to send astronauts around the Moon without landing, has also been postponed until September 2025. Artemis III, which is intended to land the first humans on the Moon’s surface since the Apollo era, is planned for no earlier than September 2026. It remains unclear whether this timeline will change further.

As for China, they could potentially achieve their plan to send humans to the Moon by 2030. Indeed, some commentators have raised questions about whether the Asian superpower could beat the U.S. in the race back to the Moon.

Geopolitics in Space

China’s space program is developing its system in a consistent and integrated manner. The nation’s missions seem to have avoided any significant mishaps.

China’s current space station, Tiangong, is operating at an average altitude of 400 km.

China plans to send at least three domestic astronauts to “permanently reside” there by the end of this decade. At the same time, the International Space Station, operating at the same altitude, will cease operations and be decommissioned in the Pacific Ocean.

Geopolitics is re-emerging as a factor in space exploration. It is likely that the U.S. Artemis III program and China’s Chang’e 7 and 8 programs will need to exchange plans and information as both aim to land at the same site near the Shackleton crater, ushering in a new era of diplomacy.

That is, while still maintaining national priorities, the two superpowers, along with their partners, may have to agree on common principles when it comes to lunar exploration.

Looking back, China has come a long way since the launch of its first satellite, Dongfanghong 1, on April 24, 1970. China was not a participant in the original space race to the Moon in the 1960s and 1970s. But now it is.