Deep within the lush forests of southern Ecuador, a large sinkhole has formed in a cloud-covered village on the western edge of the Andes Mountains.

Just over an hour later, from a small sinkhole, it expanded, swallowing enormous cobblestone roads in the historic center of Zaruma. Panic ensued among the residents as they fled their homes—grand architectural structures from the early 19th century—to safety.

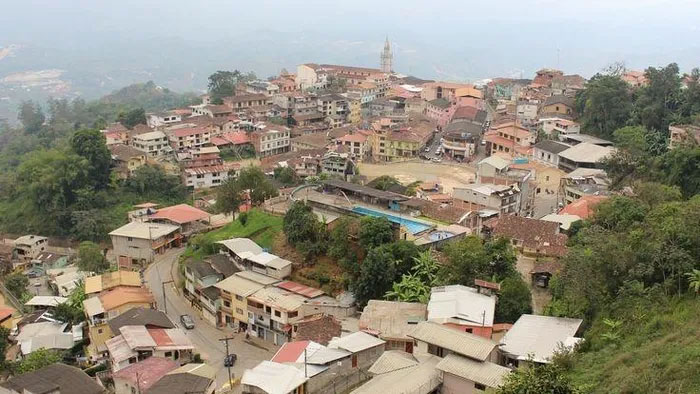

Old town of Zaruma.

The bad news quickly reached Gladis Gomez.

While passing through the town with her daughter, Gladis received a phone call. Their home, as well as her elderly father’s house next door, was in danger. She rushed home as fast as possible.

Upon arrival, she saw neighbors carrying the elderly man out of the house as the sinkhole threatened the walls. The house soon swayed and then collapsed into the ground.

The sinkhole, approximately 27 meters in diameter and 30 meters deep, had swallowed two additional houses that night, including Gomez’s. The sole cause of this sinkhole’s formation was gold mining.

Zaruma is a region rich in gold bars, the highest quality in the world. For over 1,000 years before the Incas arrived, people had come here to mine for gold. There are numerous tunnels and intricate branches, which even Ivan Nunez—a skilled engineer—has yet to fully comprehend.

One thing both Nunez and the locals are aware of: Since gold prices skyrocketed in the early 2000s, illegal mining activities have surged.

Illegal Mining

In Zaruma, everyone knows the term sableros, understood as gold thieves, who show little concern for the structural integrity of buildings and are solely focused on extracting lucrative gold veins.

If gold is located beneath schools, hospitals, or homes, they will dig regardless. Evidence of this is seen in a branch they dug from a horizontal tunnel, just 6 meters from Gomez’s house.

An illegal gold mine blocked by the government. (Photo: Bloomberg).

Nunez’s mission is to find a way to end illegal mining and stabilize the underground situation in Zaruma. Sometimes he feels discouraged: “It’s out of control.”

Officials in other developing countries face similar challenges. The high value of gold and other metals like copper, cobalt, silver, and tungsten makes illegal mining hard to resist.

Gold mining is devastating Mali, Kenya, and Congo, supplying resources for rebel armies and reducing the scale of mining.

In neighboring South American countries, gold miners are flattening forests, releasing mercury into the Amazon River, and destroying habitats.

The continent’s vast mineral resources, coupled with a widespread organized crime network, make it a hotspot. In Zaruma, gangs are linked to Mexican cartels controlling some mines.

These issues have drawn international attention.

In April 2022, Interpol warned of a rise in illegal mining activities. By June 2021, the estimated global industry was worth around $48 billion. Although these figures have not been officially updated, April’s data shows gold prices have surged, and more gangs are emerging, particularly in Latin America.

Gaston Schulmeister, head of the anti-crime division of the Organization of American States (OAS), referred to this alliance of forces as a “perfect storm.” This term describes a dire situation where many negative factors converge at once.

Schulmeister stated: “The increase in illegal mining in the region recently has been very clear, and it occurs alongside other organized crime activities such as drug trafficking, smuggling, and corruption.”

Most of these metals are funneled into global supply chains and turned into components for smartphones, TVs, and laptops. According to OAS, in places like Zaruma, this process occurs very smoothly with little government intervention.

Gold refineries often purchase both illegal and legal ore, then mix them on the same conveyor belt to conceal their origins before shipping them abroad.

The Land of Gold

The ore extracted from the mines contains only a small amount of gold, approximately 3-5 grams of gold per ton of earth and rock. This is typical for a regular commercial mine. Premium grades yield 8 grams of gold per ton. Anything above 30 grams is considered super productive.

Below the ground in Zaruma is a mining system that yields up to 180 grams of gold per ton of rock, with branches that can reach up to 500 grams.

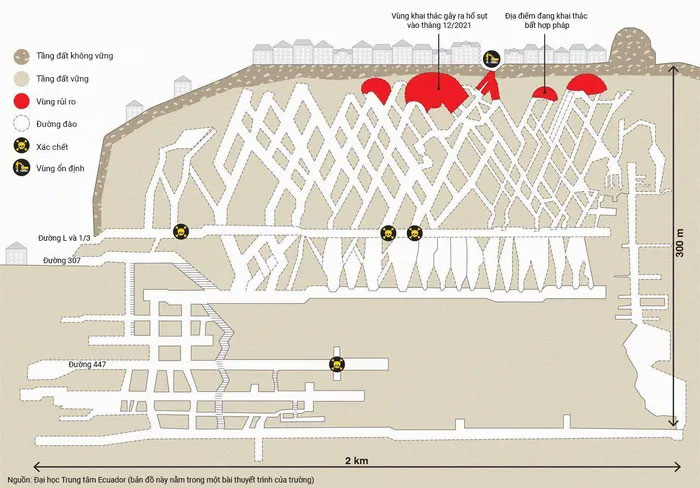

Gold mining map in Zaruma. (Graphic: Bloomberg).

According to historians, the three tribes in the area—Paltas, Canaris, and Garrochambas—were the first to discover gold. They lived here about 1,500 years ago, mining gold from the riverbed.

Around 1480, the Incas invaded, subjugating the smaller tribes and forcing them to mine metals. Later, the Spanish did the same with the Incas. When the Spanish were overthrown in the early 19th century, many large companies entered the region, starting with the Great Zaruma Gold Mining Company backed by the British.

Today, many small entities operate in the outskirts of the town. The problem is that the ore at these sites yields only a marginal amount, below 3-5 grams per ton. Centuries of mining have depleted gold in those areas.

Unless the site is beneath the cobblestone roads of Zaruma.

In the early 1990s, it was legalized that the land beneath the town could not be mined. This means that these gold mines remain relatively intact.

And that is where the sableros target.

The Dilemma

They have been digging numerous tunnels, shafts, and pits for years. The highest quality ore is located near the surface, so the tunnels are directed upwards, but this digging is perilous and can be deadly.

The sinkhole leaves a “scar” in the center of Zaruma. (Photo: Bloomberg).

Previously, a sablero named Rommel Coronel and his crew dug a massive tunnel, known as L and 1/3, running beneath the town at a depth of only 121 meters, originating from the outskirts of Zaruma. It is estimated they made hundreds of millions of dollars from this mining.

After dying from Covid-19, Coronel left behind a large path that other sableros could exploit to mine the surface layers of Zaruma. The map that Nunez’s team is piecing together is a chaotic maze of tunnels and branches.

Nunez has been in Zaruma for five months. Many sinkholes have appeared, but this latest one is the largest, causing significant damage and attracting media attention.

President Guillermo Lasso has deployed military forces to prevent sableros from mining and sent Nunez to find a technical solution. The military has failed in this mission. There are so many secret entrances that sableros have appeared continuously for three months without being controlled.

Nunez, 77, is used to meticulous oversight in high-profile projects. His plan is both simple and complex. His team will drill large wells, then fill them with cement, rocks, and sand. He believes this will stabilize the ground and block critical arteries of the sableros. Initial test runs have shown promise, and he is beginning to push them forward. “We have pinpointed exactly where to drill,” he said.

The police estimate that hundreds of sableros work in the mines, but capturing one is a challenging task. Most locals know 1-2 names but are hesitant to speak out.

One sablero, who requested anonymity, expressed fear of both gang leaders and the police when sharing information. However, he is certain that Nunez is merely wasting time here. The only thing that could stop the sableros is when Zaruma runs out of gold.

Back in town, Gomez reluctantly agrees with him.

It’s not that Gomez opposes mining. Many structures in the town are built with gold. Her husband, Roque, works as an engineer at a legal mining company and is one of three people who went down the pit to sell explosives to miners. Gold is the most valuable resource here.

The complicity of local authorities and the government with the sableros leaves her feeling bewildered. For years, one could hear sableros working right beneath their feet. Explosions could occur at any moment.

“Who can I reflect this to? Who can I report this to? No one listens. No one pays attention,” Gomez said.