Animals that have undergone head transplantation experiments have not lived long, and the technique is complex and fraught with risks in humans.

The brain is a delicate and intricate organ. The spinal cord, which connects to the brain, does not recover well after being severed. Although there have been head transplantation experiments on animals, most of these animals died within hours or days, with the longest survival being just a few months. Some researchers have attracted attention by claiming that human head transplantation is on the verge of becoming a reality, but the actual obstacles are substantial.

A two-headed dog created by scientist Vladimir Demikhov during an experiment. (Photo: Bettman/Getty)

“I don’t think any serious scientist would consider that realistic or scientific”, said Fredric Meyer, a neurosurgeon at the Mayo Clinic, in an interview with Live Science on October 19.

Historical Efforts in Head Transplantation

Scientists have never transplanted a separate brain into any animal. Living brain tissue is very soft and fragile, making it impossible to remove it from one skull and place it into another. Transplanting a separate brain would also require reconnecting many delicate cranial nerves, which presents a formidable challenge. Previous brain transplantation cases were essentially head transplants.

The first effort occurred in 1908 when scientist Alexis Carrel and Charles Guthrie transplanted the head of one dog onto another, creating a creature resembling the mythical Cerberus, which lived for only a few hours, according to a study published in the journal CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics in 2015.

This was not a success, but the work of Carrel and Guthrie contributed to medicine. Carrel later received a Nobel Prize for research related to vascular anastomosis, a technique that has facilitated organ transplantation and limb reattachment.

In 1954, Soviet scientist Vladimir Demikhov experimented with transplanting the upper half of a dog. Most of these two-headed dogs survived for a few days, with one living for up to 29 days, according to research published in the journal The History of Neurosurgery in 2016. The transplanted heads remained functional, performing actions such as drinking water and responding to visual stimuli. However, ultimately, immune rejection led to the death of the dogs.

In the 1960s and 1970s, American neurosurgeon Robert White advanced the head transplantation technique further. Using rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), he experimented with head transplants rather than transplants of the entire upper body, performing head swaps instead of adding a head to a full body, as noted in a study published in CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics in 2015. The transplanted monkeys were able to chew, swallow food, and follow objects with their eyes. However, they experienced quadriplegia because the spinal cord was severed and could not transmit nerve signals to the body. They also died within about 36 hours due to circulation issues.

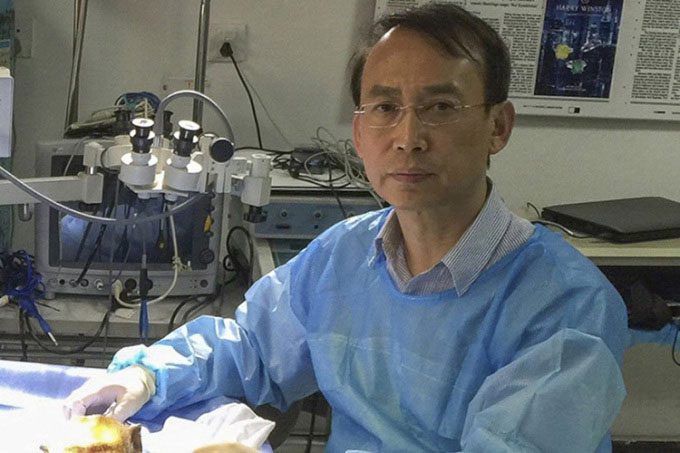

Doctor Ren Xiaoping from Harbin Medical University. (Photo: Red Door News Hong Kong)

Risks Involved

Today, immune rejection can often be prevented with advanced medications, allowing even highly immunogenic tissues like skin to survive for decades after transplantation. Scientists have also made significant advances in vascular reconnection and theoretically could maintain blood supply to the brain during head transplantation surgery.

In 2015, researcher Xiaoping Ren at Harbin Medical University in China conducted experiments on mice. He described a method of cutting one of the two carotid veins in the neck and one of the two carotid arteries to connect the head of one mouse to the body of another, while leaving the remaining carotid vein and artery to nourish the original head.

However, the experiment still faced major issues. Firstly, head transplantation requires cutting and reconnecting the spinal cord. Although Ren and his colleagues have found a way to cut the spinal cord low enough for the transplanted mice to breathe without a ventilator, there is no verified evidence in humans that the spinal cord can heal. Some scientists are researching specialized nano and polymer materials to repair the spinal cord, but these methods have only been tested on animals with nervous systems different from humans.

Preventing the brain from losing oxygen during and after surgery in humans is also more challenging than in mice due to the size and transportation of human body parts. Brain cells begin to die within just five minutes after oxygen deprivation, according to the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Additionally, there has been no research on how to manage pain following head transplantation. There is not only pain from the decapitation but also central neuropathic pain—a type of chronic pain that often occurs after spinal cord or brain injury. This type of pain is extremely difficult to manage, according to research published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings in 2016.

For these reasons, the Legal and Ethical Committee of the European Association of Neurosurgical Societies (EANS) declared head transplantation in humans to be unethical in 2016. “The risks for patients undergoing head transplantation are significant, including the risk of death. There is no verified evidence for all steps of the process, and some steps lack even experimental evidence,” the Legal and Ethical Committee concluded.