NASA’s new and most powerful space telescope, the James Webb, is delivering sharp images of distant cosmic objects.

Before the advent of advanced telescopes, the scientific community observed the universe using a rudimentary photography method with glass plates for nearly a century, from the late 19th century to the 1980s. They employed thick glass plates equivalent to window glass to capture light from stars and other celestial bodies. To map the sky, they carefully adjusted the telescope by hand, focusing on an object for extended periods.

The exposure was carried out on light-sensitive emulsion-coated glass plates, which astronomers then “developed” like film in a darkroom. They meticulously studied the transparent plates, which featured speckles representing scattered celestial bodies. These images allowed scientists to establish a classification system for celestial objects, becoming a “record” of the sky over nearly a century.

“We have evolved from the human eye to photographic plates, and now to electronic devices, as seen with the James Webb space telescope. The technological advancements allow us to build larger telescopes that can see fainter objects,” said Giovanna Giardino, a scientist at the European Space Agency (ESA).

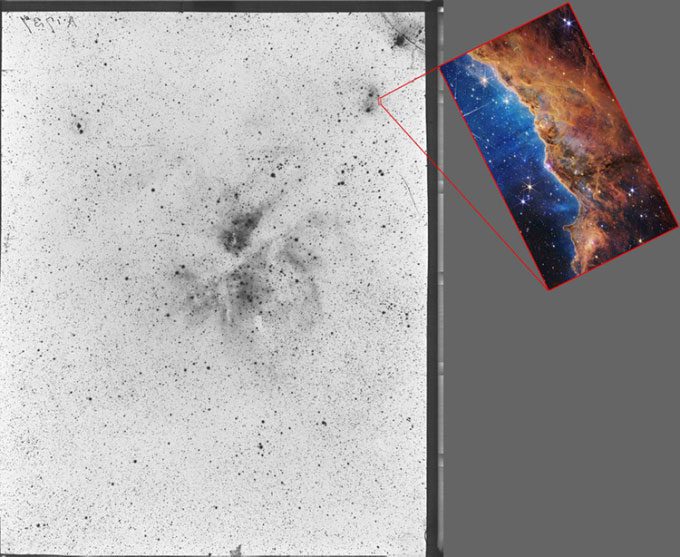

Image of the Carina Nebula (left) taken in Arequipa, Peru, on April 7, 1896, alongside an image from the James Webb Telescope (right). (Photo: Harvard University Observatory)

The Carina Nebula, a collection of gas and young stars, is located 7,600 light-years from Earth and was first discovered in 1752. The Harvard University Observatory has a collection of over half a million glass plates, including one of this nebula captured with a 61 cm telescope in Arequipa, Peru, in 1896.

In July 2022, James Webb also captured the Carina Nebula, but there is a significant difference in scale between the two images. James Webb’s magnification capability exceeds that of what astronomers could capture with photographic plates by over 100 times, according to Nico Carver, a librarian at the Harvard University Observatory.

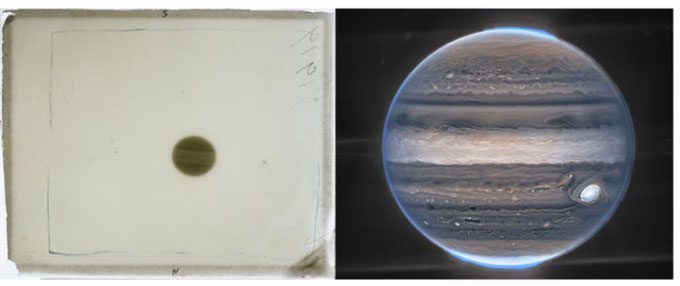

Image of Jupiter taken at Mount Wilson, Nevada, in 1889 (left) alongside an image from the James Webb Telescope in 2022 (right). (Photo: Harvard University Observatory)

The historical image of Jupiter reveals hazy cloud bands and the Great Red Spot—a massive storm that has been active for centuries. The photo, taken in 1889 at Mount Wilson, Nevada, used a 33 cm telescope, according to Carver.

The image of Jupiter captured by James Webb in July and released in August shows the planet’s turbulent atmosphere and the Great Red Spot in astonishing detail. James Webb also detected Jupiter’s thin rings, formed from dust particles, and auroras at the northern and southern poles.

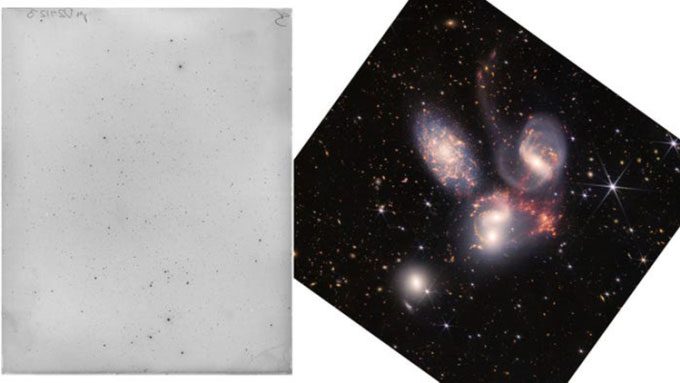

Image of Stephan’s Quintet taken at Oak Ridge Observatory in Massachusetts on October 1, 1937, alongside an image from the James Webb Telescope in 2022 (right). (Photo: Harvard University Observatory)

Stephan’s Quintet, a group of five galaxies located 290 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Pegasus, was first discovered in 1877. Four of them are gravitationally interacting in a slow merger, while the fifth galaxy is much closer to Earth, about 40 million light-years away.

Stephan’s Quintet appears very faint in images taken from the previous century. However, on July 12, when James Webb released its first series of images, this galaxy group emerged with unprecedented detail.

One of the main reasons James Webb can capture such sharp images of Stephan’s Quintet is its ability to detect infrared light. NASA stated that this is a massive image created from nearly 1,000 photos, containing over 150 million pixels. The increased pixel count allows astronomers to capture higher resolution scenes, according to Giardino. “This is a major advancement,” she remarked.