-

Construction Period: 1850 – 1851

-

Location: London – England

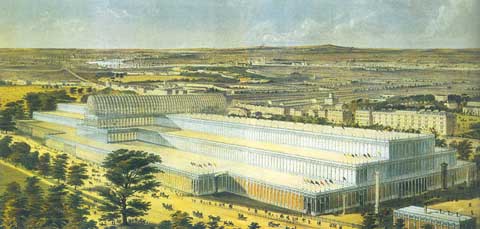

As a product of industrial production and assembly, Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace is one of the most innovative buildings of the 19th century. The palace is often seen as a symbol of modernity, and much of its achievement remains unparalleled today. Designed and constructed in less than 8 months, this was the time when the most massive enclosing walls created an artificial landscape with an indescribably thin, transparent shell. Initially viewed as a temporary structure located in a park for just one year, it had to be dismantled as quickly as it was built – a spectacular achievement that was fleeting.

|

|

Constructed in Hyde Park, central London, to celebrate the economic and cultural achievements of the British Empire, the Crystal Palace is regarded as an open system made from a set of many industrially produced components assembled together. |

The idea of holding a large Exhibition as a celebration of peace, personal prosperity, and free trade – all viewed through the lens of the British Empire – originated from the Royal Society of Arts, under the patronage of Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria. In early 1850, the Royal Commission was established to oversee the project, proposing designs and soliciting bids for a building covering 74,350 square meters (800,000 square feet) with a budget of £100,000 to be completed in just 15 months. The bid documents specified that “all loss-cost construction methods would be considered.” Although hundreds of plans were submitted, the committee members could not agree on which design to choose and decided to design the building themselves. The resulting design, featuring about 17 million bricks, clearly did not meet the budget and timeline requirements.

Construction with Glass.

|

|

The glass and wood envelope of the Crystal Palace was developed as a glazing system based on a modular design of 1.2m; many inventions were made to reduce structural weight and standardize the production of building components. |

The project was supported by Joseph Paxton, a gardener with 20 years of experience in greenhouse construction. His most significant achievement up to that time was the Great Conservatory, completed in 1840, at the luxurious Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, where he managed the groundskeepers. Most of his innovations in this project were directly applied to the construction of the Great Exhibition, albeit on a much larger scale.

Collaborating with glassmaker Robert Lucas Chance, the glass panels in the Great Conservatory were 1.2m long but only 2mm thick and extremely lightweight. As larger glass panels had never been produced before, this thickness aligned perfectly with Paxton’s 1.2m modular concept, and the lightweight nature allowed him to significantly reduce the number of sliding glass frames required and the support structures. The structure was further lightened using a system of glass installed along the ridge and the valley that reduced the span of the sliding glass frame bars by sliding diagonally from the ridge to the valley instead of along the length.

To save time and money and to increase accuracy, Paxton devised a steam-powered machine to standardize the production of wooden framing strips designed to fit the valleys, concentrating condensation inside and collecting rainwater outside. Ultimately, he developed the “Paxton Gutter”, a flat wooden gutter shaped with a supporting frame at the bottom to facilitate rainwater drainage.

Paxton’s innovations in the Great Conservatory focused on wood and glass, using iron sparingly only where truly necessary in the structure. He viewed the glass and wood envelope as a systematic constant, repeating itself – a “fabric” draped over an iron framework that could be adjusted to meet specific site requirements and construction plans. The rigidity and lateral stability of the table allowed the “fabric” to be thin and lightweight. In 1849, when Paxton built another greenhouse at Chatsworth for the famous Victoria regia water lilies, he asserted that the rigid ribs on the underside of the lily pads inspired him to conceive the two-dimensional structural table.

Actual Figures:

-

Length: 554.4m

-

Width: 122.4m

-

Height of the central nave: 19.2m

-

Height of the transepts: 32.4m

-

Floor area over 3 levels: 92,000m²

-

Construction area: 7.7ha

-

Cast Iron: 3,800 tons

-

Wrought Iron: 700 tons

-

Wood: 55,762m³

-

Glass: 293,655 panels, 250mm x 1225mm, 83,610m³

-

Gutter length: 38.6km.

-

Bid price: £79,800

-

Final cost (including fixtures & fittings): £169,998.

|

|

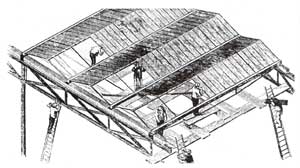

To expedite construction, the pre-fabricated components of the central dome were assembled on the ground. To alleviate the feeling of a narrow interior width of the aisle, the completed dome was hoisted at an angle. |

In June 1851, Paxton learned from friends that the Royal Commission was struggling to agree on a satisfactory design and convinced them to allow him to participate. Collaborating with the Chance brothers and contractor Fox Henderson & Co., using the system he developed in his previous greenhouses, Paxton’s design was the only one that met the budget and schedule requirements, which had now been reduced to just 8 months.

Construction Process

Two weeks after Paxton’s bid was accepted, Fox Henderson began construction. The design, manufacturing, and assembly of the building’s components progressed at an unprecedented pace. The project was hailed as the first application of Adam Smith’s principle of division of labor in architectural works. In stark contrast to the architectural characteristics of the era, construction was not viewed as a formality but as a process. Like the railways, which were a focal point of innovation in the 19th century, the form was a nebulous, dynamic system, emerging from a toolkit of standardized components.

Each design component adhered to Paxton’s 1.2m planning module. To reduce the number of components and lighten the construction process, each element was designed to perform two or three functions: wooden strips for sliding glass frames also served as gutters, hollow cast iron columns acted as rainwater downpipes, and scrap from the site was repurposed as flooring. Components were manufactured in workshops across England on a production line, each worker described by architectural critic Matthew Digby Wyatt as “acting precisely like the various parts of a perfectly designed machine, skilled in their own field, without knowledge of the tasks of others.” Building materials were transported to London by rail, delivered directly to the site where they were assembled immediately to clear space for storing materials.

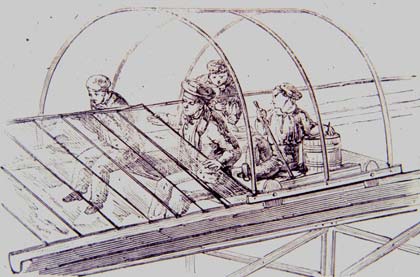

The number of defective components did not exceed one ton, and the construction was mainly assembled by hand, occasionally assisted by horses. The span of the central vaulted aisle, 22.8m wide, was made with iron and wooden ribs shaped into a semicircle, assembled on the ground and lifted by winches at an angle so that the narrow interior width of the dome was no longer visible. Special equipment designed by Fox Henderson aimed to expedite the assembly process on site. Hand-pushed carts with wheels were ingeniously used as gutters to transport both people and materials, reducing the need for scaffolding for glass installers. Using these carts, a team of 80 workers could install 18,000 glass panels each week. By December 1850, as many as 2,260 workers were employed on the site, coordinating closely in their tasks.

|

|

|

Working with Paxton, the contractors designed a special tool to expedite assembly. Hand-pushed carts served as gutters for transporting both people and materials, reducing the need for scaffolding for glass installers. (Image: intranet.arc) |

The construction of the Crystal Palace, which utilized no mortar and involved assembling components produced in distant locations right on site, represented a rapid and safe alternative to conventional building practices. This innovative approach excited both workers and the public alike. The construction of the building became a sensational event, attracting large crowds and receiving daily media coverage, earning it the name “Crystal Palace.”

The process of construction, along with the organization of manpower, machinery, and materials on a large scale, served as a vivid demonstration to the public of the logical efficiency in terms of time, scope, and movement. This inspired Henry Ford to invent the automobile assembly line. Thanks to the transparency and clarity of the system, the construction of the Crystal Palace celebrated industrial strength even more than a large-scale exhibition could.

|

|

The largest enclosing wall at that time had never been constructed before. The Crystal Palace enveloped the existing mature trees in Hyde Park, with its thin transparent shell creating a new ambiguity between the interior and exterior spaces. (Photo: canadianarchitect) |

After 6 months of construction and 4 months following the erection of the first cast-iron column, the Crystal Palace was completed and handed over to the Royal Commission for installation and exhibition. On May 1, 1851, Queen Victoria inaugurated the grand exhibition, which was a resounding success, drawing over 6 million visitors in just 5 months. Besides the significant profits, the exhibition birthed the idea of transforming the site into a large national entertainment center, signaling an era of consumerism and giving rise to a new type of building designed for selling goods – the modern department store.

Combined with many existing trees in Hyde Park, the arched structure with elegant glass walls created a new experience, blurring the lines between indoor and outdoor spaces, art and nature. The Crystal Palace also sparked debate over the distinction between architecture and construction. Studies illustrating the tension between practicality and the construction process showed that the architectural profession did not recognize this structure, even though it was not poorly designed.

The grand exhibition concluded as planned in October 1851. In 1852, the dismantling of the Crystal Palace occurred swiftly and notably, just as it had been erected, ending a short yet spectacular life that captured the public’s imagination. The components were acquired by a new company founded by Joseph Paxton, who, after significant design modifications, reassembled them at a site in South London, now known as Crystal Palace. It took 2 years to complete, serving as a venue for miscellaneous exhibitions and concerts, though it never achieved economic success and faded from public memory. Ultimately, the structure was completely destroyed by fire in 1936.

Crystal Palace (Photo: intranet.arc)