The aurora, typically found in the Arctic and Antarctic regions, has captivated and intrigued humanity for centuries and will continue to draw attention in the future. The shimmering arcs of the aurora borealis (in the Northern Hemisphere) and the aurora australis (in the Southern Hemisphere) have recently created spectacular light displays.

In late February and early March, many photographers and night sky observers in the Northern Hemisphere captured these colorful displays at locations further south than usual, such as Colorado, USA, southeastern England, and New South Wales, Australia. Pilots have even maneuvered their planes in mid-flight to allow passengers to get a clearer view of this phenomenon.

Aurora borealis captured on the night of February 27 above Souter Lighthouse in South Shields, northeastern England. (Photo: CNN).

Sunspots

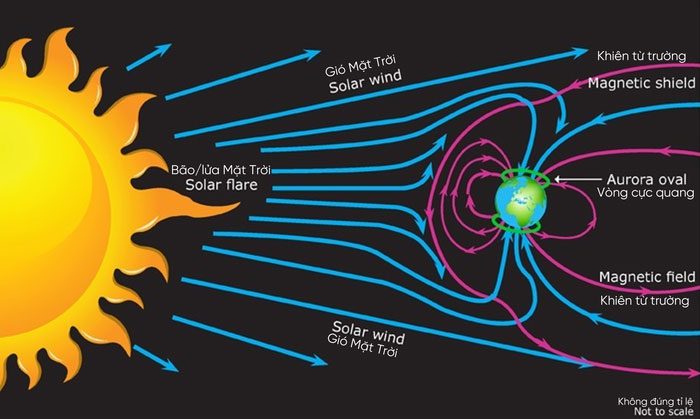

The auroras are the result of solar activity, specifically a type of solar storm known as a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME), which releases gas and charged particles into the atmosphere. When these charged particles reach the Earth’s magnetic “shield” at the North and South Poles (usually taking about three days), they enter the atmosphere.

From here, the particles and energy interact with gases in the atmosphere, creating colorful lights in the sky. Oxygen corresponds to green light (the most frequently observed color) as well as red (according to Aurora Watch, Lancaster University, UK). Meanwhile, nitrogen emits blue and purple light, according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Under favorable weather conditions, observing the aurora will be easier.

When a solar storm approaches us, some energy and small particles may move into the “shield” of the magnetic field at the North and South Poles and interact with the Earth’s atmosphere. (Illustration: Science Learning Hub, NZ).

Researchers at NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory reported that they detected two M-class solar flares on March 3 and 4 that triggered CMEs, thus increasing geomagnetic activity – leading to the captivating auroras. These bursts are categorized from small to large in levels: A, B, C, M, and X, with X being the maximum level, according to NASA.

These types of solar storms also occasionally disrupt artificial satellite activities and communications on Earth.

The increase in geomagnetic activity is generated by a sunspot on the Sun’s surface (sunspots – a phenomenon recorded as early as 800 BC). This sunspot “is large and complex in terms of magnetic field” and is named AR3234, according to the UK Met Office.

Aurora scene in Anchorage, Alaska (USA), captured by resident Stephanie Quinn-Davidson.

How Common Are Auroras?

This strong activity of geomagnetic phenomena is predicted to begin to ease. This means there will be fewer auroras following the recent periods of intense auroral activity.

In the coming years, the aurora may appear further south more frequently, according to Robert Massey, executive director at the Royal Astronomical Society.

The Sun goes through an 11-year cycle where the level of solar storms and flares fluctuates. The most recent Cycle 25 began in December 2019 with a phase of solar minimum, when solar activity is quieter and there are fewer sunspots.

Auroras recorded across the UK, including in the southern regions of the country. (Photo: Twitter)

We are heading towards a solar maximum, predicted to begin in July 2025, when a large number of sunspots will appear and solar activities will increase.

Robert Massey stated that the solar phenomena that create auroras will become more common as we approach the solar maximum. Other planets in the Solar System also experience auroras.

Jupiter is bathed in fascinating colors at its poles, although the mechanism that creates auroras on this planet differs from that on Earth, according to a 2021 study.