Despite nearly one-quarter of the world’s population living in China, they only occupy 7% of the world’s arable land (2002). Additionally, there has been continuous loss of arable land in China due to erosion, salinization, desertification, and urbanization. This loss of land has reached alarming levels, estimated at around 300,000 hectares per year (2003). This has created serious social issues such as localized famine and food scarcity, pollution, and land degradation. The Chinese government views agricultural biotechnology as a tool to: improve the nation’s food supply, increase agricultural productivity, boost farmers’ incomes, promote sustainable development, and enhance competitive positioning in the international market. (Huang et al., 2001) Advanced agricultural technologies, such as biotechnology, will become extremely important in ensuring food security in China (Kowalski, 2003). In response, the government has created substantial resources for this sector and actively promoted its development since the mid-1980s. (Huang et al., 2001)

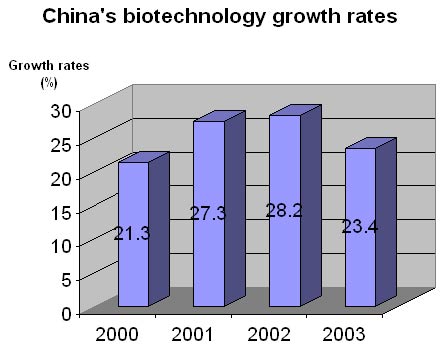

The biotechnology sector in China has achieved significant scientific success and development, but it remains largely government-supported. This success has led to a rapid increase in financial support in recent years. In the latter half of the 1990s, biotechnology funding more than doubled from approximately $40 million to $112 million per year. The Chinese government has pledged to increase research budgets by 400% over five years from 2002 to 2007.

The biotechnology sector in China has achieved significant scientific success and development, but it remains largely government-supported. This success has led to a rapid increase in financial support in recent years. In the latter half of the 1990s, biotechnology funding more than doubled from approximately $40 million to $112 million per year. The Chinese government has pledged to increase research budgets by 400% over five years from 2002 to 2007.

China’s total spending on agricultural research and development is estimated to be about 10% of global public spending, despite being a developing country. There are currently nearly 400 major biotechnology laboratories funded by the government and over 20,000 technical and research staff working in the industry (as of 2002).

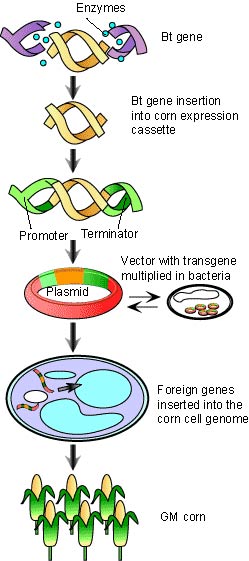

Research efforts have yielded many genetically modified varieties that have been field-tested, environmentally cleaned, and commercialized. Genetic modification has various goals (or combinations of goals): insect resistance, fungal resistance, virus resistance, salt tolerance, drought resistance, enhanced nutritional quality, and increased yield (2002). China ranks fourth globally in the area of commercially grown genetically modified crops, following the United States, Canada, and Argentina. China was the first country to commercially cultivate genetically modified crops—starting with tobacco. After planting 1.6 million hectares of genetically modified tobacco in 1996, China ceased its cultivation due to concerns that tobacco processors, mostly from the U.S., would ban the import of genetically modified tobacco (1999).

Six crops have been granted commercial production licenses. Two licenses were awarded for different insect-resistant cotton varieties. In 2000, genetically modified cotton was cultivated on an area of 700,000 hectares (2001). Two other licenses were granted for tomato varieties, one modified to slow ripening and the other resistant to viruses. Genetically modified ornamental tobacco and sweet potatoes resistant to viruses have also been licensed. Monsanto, based in the U.S., is the only foreign company licensed to produce genetically modified cotton. (2002)

The use of biotechnology in non-agricultural sectors occupies a smaller portion of this industry compared to agricultural biotechnology, but it is a critical part of the government’s plan to address some of China’s most serious problems. In total, 18 biopharmaceuticals have been commercialized, with an additional 30 biopharmaceuticals undergoing clinical trials. China has also made progress in developing biopesticides (2001). Furthermore, China has developed genetically modified carp (a species abundant in China) that grows 42% faster than non-genetically modified carp.

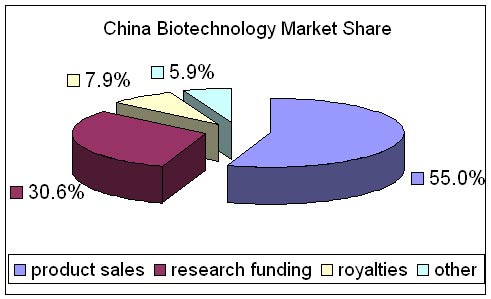

The business of biotechnology products is becoming increasingly important. From January to April 2003, biotechnology imports reached $36 million. During the same period, biotechnology exports totaled $60 million. In April 2003, biotechnology imports fell by 43%, partly due to seasonal factors and partly due to changes in regulations and the instability caused by these changes.

However, in the four months from January 2003 to April 2003, imports increased by 6.9% compared to the previous four months. Exports grew even more robustly. (Ministry of Commerce, 2003). Specifically, soybean imports from the U.S., with over 70% being genetically modified, reached $1 billion per year. This is the only and largest soybean import market for the U.S. The most significant genetically modified export product from China is cotton—51% of which is genetically modified.

China’s Biotechnology Policy

The Chinese government’s biotechnology policy is a crucial factor in encouraging both domestic private production and international investment; however, thus far, the policy has remained contradictory, ambiguous, and lacking clarity, especially for international companies.

The Chinese government’s biotechnology policy is a crucial factor in encouraging both domestic private production and international investment; however, thus far, the policy has remained contradictory, ambiguous, and lacking clarity, especially for international companies.

While the Chinese government significantly financially supports the biotechnology sector and declares the social benefits biotechnology will bring, its commitments in terms of regulations are often less resolute and increasingly unclear. The President of Monsanto in China, the only foreign company with a genetically modified license, stated, “(China) is accelerating the process by funding research and development in biotechnology, but simultaneously is applying brakes through regulation.” The lack of clear and consistent guidance from the government has created an extremely risky business environment for those wishing to export genetically modified products to China or invest in biotechnology-related activities, including research.

In January 2002, China introduced import regulations requiring labeling and quality certification for all genetically modified crops and plants imported into China for sale, production, processing, or research. Obtaining an import permit for genetically modified products is a complex process that can take up to 270 days, and the requirements of this process can pose significant trade barriers.

While imports are scrutinized rigorously, domestic producers are exempt from regulatory barriers. In May 2001, the State Council of China issued the “Regulations on the Safety of Agricultural Genetically Modified Microorganisms.”

The general rules underpinning these new regulations include that biosafety for genetically modified crops and microorganisms, as well as the associated risks, should be assessed on a case-by-case basis, by type, by strain, and in a tiered fashion. Decision-making should be based on risk expressions, biosafety reviews should focus on scientific questions and data, expert panels should play a crucial role in the decision-making process, and regulatory requirements should be consistent and clear. When assessing the safety of genetically modified crops, regulators will base their regulations on several key parameters such as the characteristics of the microorganisms, trait incorporation, and usage, the interactions the microorganisms will have with environmental factors, and the combination of all these factors.

(Image: Pacontrol)

Once genetically modified crops are approved and enter the Chinese market, they may be subject to strict labeling requirements. State authorities are still working to establish and clarify these requirements for various product types. The Chinese government hopes that these regulations will ensure that biotechnology products developed in China for domestic consumption and international trade do not pose health and environmental risks. These regulations have hindered efforts to commercialize certain crops such as rice and corn.

Overall, it seems that China is beginning to implement increasingly stringent rules for genetically modified food and crops in particular. While policies prioritize and support non-food genetically modified products, concerns over food safety both domestically and internationally have begun to influence government regulations and policies regarding genetically modified foods. Some Chinese scientists argue that this cautious approach indicates that the next generation of genetically modified crops, including staple products like rice, could be consumed by billions of people worldwide, and the safety of these foods now rests in China’s hands.

Consumer Acceptance of Biotechnology in China

The acceptance of biotechnology by Chinese consumers brings enormous potential profits to companies looking to produce biotechnology products. Consumer attitudes are significantly influenced by the government, as it controls the media. An international consumer survey across 10 countries shows that China has the highest support for biotechnology products among the surveyed nations, including the United States, Canada, Japan, Russia, India, and four European countries.

Due to state management of the media, if the government’s stance on biotechnology changes, consumer attitudes will almost certainly follow suit.

Due to state management of the media, if the government’s stance on biotechnology changes, consumer attitudes will almost certainly follow suit.

Emerging Issues in China’s Biotechnology Sector

While the domestic biotechnology sector is becoming one of the leading biotechnology hubs globally thanks to significant government funding, it faces tremendous challenges and has several fundamental issues that need addressing for the industry to succeed. As mentioned earlier, nearly all biotechnology programs are driven by the Chinese government. However, funding does not come without specific restrictions, especially in a society where centralized control is the norm.

Consequently, there are numerous conditions attached to receiving grants, specifically determining which crops and traits research will focus on. While most biotechnology entrepreneurs prefer private funding sources, private investors hesitate to use their resources until they know that regulatory mechanisms will provide a reasonable opportunity for them to recoup their investments.

Another significant challenge is managing the extremely complex agricultural biotechnology development efforts in China. The lack of coordination between program management and individual researchers has contributed to unnecessary and inefficient development efforts, particularly at the local level. This results in fewer technological advancements that are more costly.

The Chinese government’s failure to provide clarity on future policy direction has left foreign governments, particularly those in the European Union, extremely concerned that there will not be sufficient attention to establishing and enforcing regulations to ensure food safety and address consumer and environmental concerns within the EU. As a result, they have pressured the Chinese government to adopt stricter safety standards. The Chinese government has yet to strike a good balance between ensuring the safety of its products, satisfying international concerns, and encouraging industry growth. If the Chinese government cannot find this balance, not only will state-owned companies continue to receive substantial subsidies, but the uncertainty will also deter domestic and foreign private investors.

While the strong consumer support for biotechnology products in China is a significant advantage now, it is uncertain in the long term. Although limited information suggests that Chinese consumers are highly conscious, they also possess little accurate knowledge about genetically modified foods. Since Chinese consumers have not experienced debates related to the safety of biotechnology, their views could easily shift if negative reporting arises in the future.

The Chinese government has implemented restrictions on foreign investment in a bid to ensure that what they perceive as an essential industry for the future remains under domestic control. The cost may be a loss of opportunities for technology transfer. In April 2002, China issued the “Catalogue for Guiding Foreign Investment Industries.” This new regulatory mechanism prohibits foreign investment in the “production and development of genetically modified seeds.” These regulations are among the most restrictive in the world regarding the production, research, and importation of genetically modified organisms. While this creates immediate profits for China’s biotechnology sector by avoiding foreign competition in the lucrative seed development business, they risk going it alone and failing. If China falls behind foreign seed suppliers, farmers may turn to smuggled seeds.

Future Prospects for China’s Biotechnology Sector

Although China’s biotechnology sector faces significant challenges, the mid-term prospects appear relatively positive. China is undergoing a phase of deep and broad changes in how domestic markets and international trade mechanisms operate, particularly concerning government intervention in the economy. While, ultimately, this change will likely benefit both China and its trading partners, in the short term, the level of uncertainty will limit investment enthusiasm in the Chinese market.

One of the most crucial factors for the long-term success of the biotechnology sector is that the motivation for success arises not only from the availability of profit opportunities, as is the case in most developed countries, but also from the awareness that biotechnology can help address some of China’s most pressing social issues. With China’s continuously growing population demanding sufficient food and land resources, finding alternative means to resolve these issues is of even greater concern. Faced with these pressures, China may pay more attention to the potential benefits of biotechnology and less to the risks compared to developed countries.

The Chinese government must carefully reconsider its policies limiting foreign investment in the biotechnology sector, as China risks: angering other governments to the point of filing formal complaints with the WTO and isolating its biotechnology sector from advancements made in other countries, potentially causing China’s biotechnology industry to fall behind its competitors.

Thanh Vân (Compiled)