-

Construction Period: from 1506 – 1666

-

Location: Rome, Italy

In the summer of 1505, Pope Julius II decided to demolish the most sacred monument in Christendom – the church built by Constantine over 1,000 years earlier on the tomb of Saint Peter – and to reconstruct it. The new basilica was to be one of the wonders of the world, on an unprecedented scale. More than 200 years later, a succession of talented architects continued the work, and the final result fulfilled Julius’s ambitious vision. St. Peter’s Basilica stands as an incredible testament to confidence, grandeur, and authority.

|

| The medal cast in 1506, marking the beginning of St. Peter’s construction, is almost the only record of Bramante’s initial intentions. |

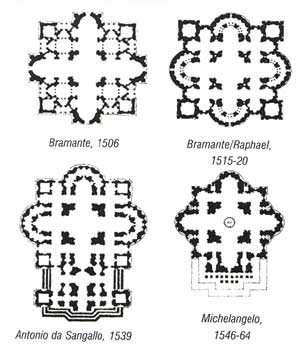

The architect chosen by Julius was Donato Bramante, a genius who introduced the pinnacle style of the Renaissance in Rome. Both he and Julius shared the bold plan to construct the new St. Peter’s Basilica: a centralized (symmetrical in all four directions) church in the form of a Greek cross with four arms ending in semi-circular chapels, topped with a hemispherical dome. This dome was to rest on four main supporting piers, buttressed by smaller dome chapels above. The façade was to feature two towers. Almost the only information about this church comes from the patchwork diagram and the medal depicting the structure issued in 1506.

Initially, the construction progressed rapidly, focusing on the four large arches to support the dome, but after Julius’s death in 1513 and Bramante’s the following year, the pace of construction slowed. The issue was cash flow. Julius’s successor, Leo X, raised funds by selling indulgences – ensuring sins were forgiven – leading to Luther’s protests in Wittenberg. Thus, St. Peter’s Basilica became one of the catalysts for the Reformation.

As Bramante’s successor, Leo X appointed Raphael, a strange choice as he was not an architect and relied solely on the technical advice of Antonio da Sangallo. The back of the old basilica was demolished to build a structure resembling a shrine above Saint Peter’s tomb to protect it. Work at this point was nearly halted while debates continued on how to proceed – whether to follow Bramante’s centralized plan or adhere to a more traditional layout with a longer nave.

The view of St. Peter’s Basilica from the roof of the Bernini colonnade

shows the dome as envisioned by Michelangelo dominating the façade

in a way that is currently obscured by Maderno’s nave.

Numerous drawings from the 1520s and 1530s depict the gigantic domes rising above the temporary basilica while the hollow walls of Constantine’s nave remain bleak in the foreground. Almost all the treasures accumulated over the centuries, including the tombs of the Popes, were ruthlessly smashed.

From Raphael’s death in 1520 until Michelangelo’s appointment in 1546, various plans were sketched, some centralized and others longitudinal, but there were no significant improvements at the ground level. Antonio da Sangallo detailed a model, which still exists, but this plan was never executed. This was a difficult period for the papacy, marked by the sacking of Rome and the rise of Protestantism.

A New Beginning

|

| The grandeur as envisioned by Michelangelo is now clearly visible from Vatican Park and rarely seen by the public. |

Michelangelo was the choice of Pope Paul III. He reluctantly took on the task, without pay, “for the love of God,” and immediately reverted to Bramante’s original design. He stated: “Anyone who derives from Bramante’s idea derives from truth.” His architectural concept, however, contrasted with Bramante’s ideas. Instead of a logically related geometric shape, he perceived mass and space as expressions of irresistible forces. This fundamental architectural concept made him a pioneer of the Baroque style as a result of the Renaissance. He significantly increased the thickness of the main supporting piers and outer walls, believing (correctly) they were too weak to support the massive dome. By the time of his death in 1546, St. Peter’s Basilica had developed into the form of a polygonal drum under the dome, with detailed models prepared to clarify his intentions.

The next architect, Giacomo della Porta, did not strictly follow his design, but the main structure still reflected Michelangelo’s ideas. The dome was constructed in two layers: an inner hemispherical shell visible from within, and another, slightly sharper shell visible only from the outside. The dynamic ribs are divided into multiple converging arches at the apex, creating a lasting impact on the dome’s design to this day.

The true impact of Michelangelo’s imagination can only be fully appreciated from the perspective of Vatican Park. From here, a complex hierarchy of forms emerges – the style of the gigantic buttressing columns, with openings that seem too small for them, the vaulted ceiling with intricate windows, and a robust belt of paired columns encircling the polygonal walls beneath the dome, along with the towering shape of the dome itself – creating an unforgettable dynamic impression.

|

| Four development stages of St. Peter’s Basilica, reflecting various solutions proposed by four architects. As a result, when considering the liturgical requirements, a long nave was needed, combining the ideas of Bramante and Michelangelo. |

Michelangelo believed that the same vitality could be seen from the façade, but the façade was never built, and the idea of a previous nave (the Latin cross plan) was once again brought to attention. In 1607, a committee of ten architects made the final decision, with Carlo Maderno, one of the first architects of the Baroque generation, taking on the task, completing the nave within ten years.

Completion of St. Peter’s Basilica

It took a considerable amount of time to complete St. Peter’s Basilica, and the construction techniques employed certainly evolved. For several years during the project, the workforce reached up to 2,000 people. This was the initial count when Bramante contracted with five assistant architects, who then hired many skilled laborers paid by piecework to execute every detail on each square meter of the pavement, walls, and roof.

Bramante’s intersection never supported the dome as he envisioned and left the rectification for Michelangelo. Under his supervision, a large workforce was mobilized. As construction rose, he added spiral earthen ramps for mules to haul stone upwards. Often, the current Pope’s active involvement was crucial. While Della Porta was building the dome, all resources were forcibly mobilized, and up to 800 workers were employed in day and night shifts to carry out the work.

The same situation occurred during the construction of Maderno’s nave. In 1600, a skilled workforce emerged, comprising bricklayers, painters, plasterers, glaziers, and gilders, reflecting the reality that at this time, the project focused on decoration as much as on structural integrity. These specialized functions would be passed down from father to son, with the entire group of workers known as “Sampietrini“.

Most of the stone used in St. Peter’s Basilica was sourced from quarries in the surrounding area, such as tufa from Port Portense and travertine from Tivoli. The wooden scaffolding necessary for constructing Maderno’s curved dome was itself an engineering marvel, and all the timber was transported from Rome. More than 1,000 workers were recruited for construction and for demolishing, clearing away the last remnants of the old basilica.

|

| Inside the intersection of the grand St. Peter’s Basilica: A space conceived by Michelangelo, but decorated according to Bernini’s vision. This watercolor painting by Louis Haghe depicts a papal procession (1864). |

No one wanted to take on the work of Maderno. To elevate the structure both externally and internally, he had to adhere to Michelangelo’s ideas. Designing a new façade turned out to be a mistake, resulting in a final product that did not accurately reflect Maderno’s talent. Instead of a true Baroque façade, he accepted Michelangelo’s original layout, interpreted in a dull, heavy manner that evoked no admiration. Particularly unfortunate was the cancellation (for structural reasons) of the towers that were supposed to support the arches of the nave. At this point, the width was disproportionate, while the length of the nave indicated that the dome’s peak could not be seen except from a distance.

Actual Measurements:

-

Interior Length: 183m

-

Total Length, including the portico: 213m

-

Width of the transept: 137m

-

Height of the dome with the skylight: 138m

-

Diameter of the dome: 42m

-

Width of the nave: 25m

-

Width of the portico: 71m

-

Width of St. Peter’s Square: 198m

Bernini’s Contributions

The last renowned architect to contribute to the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica was Gianlorenzo Bernini, a master of the Baroque style. For most visitors, it is unfair to attribute the overall impression of both the exterior and interior solely to Gianlorenzo Bernini. Inside, the expansive altar (completed in 1633) above St. Peter’s tomb features a towering bronze baldachin supported by twisted columns, while the exterior showcases a vast oval colonnade of deep fluted Tuscan columns (completed in 1666) that encircle St. Peter’s Square, adding the grandeur that Maderno’s façade lacks.

The rich decoration and interior woodwork of St. Peter’s Basilica—its monumental mosaics (many larger than life), wood engravings, stuccoes, and countless tombs of popes—were also the work of Bernini, all of which inspire admiration without his touch. St. Peter’s Basilica always possesses an infinite quality, and while it cannot be claimed to represent the unified vision of a single individual, it is indeed a unique expression of a highly creative nation over two centuries.

From above, it is easy to recognize Bernini’s Piazza,

enclosed by the oval colonnades.