If there is a most controversial custom in South Asian culture, Sati – the practice of self-immolation by widows in India surely tops the list.

On one hand, it is an act that demonstrates absolute loyalty, while on the other, it reflects extreme patriarchal bias, so brutal that it strips away the very life of a widow who is already in a pitiable state.

Origins and Abuse

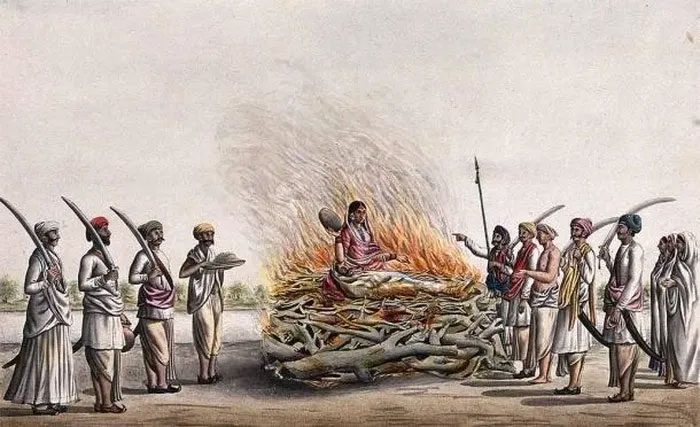

Non-consenting widows are forced into Sati. (Image source: Ancient-origins.net).

Sati is a Hindu religious custom named after the goddess Sati. Hindu mythology tells that Sati was a goddess who disobeyed her father to marry the god Shiva. In a fit of rage, after being disrespected by her father, she self-immolated to protest, and before entering the flames, she prayed to be reborn as Shiva’s wife in her next life.

This wish was granted, and she was reborn as Parvati, continuing her marital connection with Shiva. Hindus greatly admire Sati’s devotion, leading many to emulate her act of self-immolation. When a husband dies, the widow is expected to voluntarily follow him to the afterlife, instead of living as a widow.

The exact time when Sati was practiced is still uncertain, but the earliest records of it likely date back to the 4th century BCE. The esteemed Greek historian Aristobulus of Cassandreia (375 – 301 BCE), during his travels to India with Alexander the Great (356 – 323 BCE) in 327 BCE, recounted this custom. Other historians of the time, such as Cicero, Nicolaus of Damascus, and Diodorus, left similar accounts.

Historians speculate that initially, Sati was only practiced in certain regions, as other historians who visited India did not mention this custom. It was not until around 400-500 CE that it became widespread, dominating the spiritual life of India from 1000 CE onward.

Indian society is divided into four castes: Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (royalty and warriors), Vaishyas (craftsmen, merchants, farmers), and Shudras (laborers). The first group to practice Sati was likely the Kshatriyas, who set an example for the secular world.

Some historians also suggest that Sati was combined with Jauhar, a practice of self-immolation to preserve the dignity and chastity of high-status women. This combination altered the meaning of self-immolation from an “act of bravery” to an “act of virtue” and an “act that should be done.”

Under the interpretation of “an act that should be done,” Sati encompasses both voluntary and coercive elements. If a widow does not voluntarily self-immolate to follow her husband, society may force her to do so. There are several methods of Sati, but the most common involves the widow sitting or lying next to her husband’s corpse on the funeral pyre, accepting death by fire.

Decline and Survival

Currently, Sati still quietly occupies a corner of spirituality and life in India. (Image source: Reddit.com).

Contrary to the elaborate religious justifications, the real reasons behind Sati are rather bitter. In Hindu society, women are not given any role or status and are seen as a burden.

To avoid the stigma of discarding them, Sati emerged as the most direct and radical solution. Typically, widows who performed Sati were those without children. The practice prohibits pregnant women or those caring for small children from participating, and it also exempts women from high castes.

The first to find Sati brutal and seek to end it was Emperor Akbar (1542 – 1605), the third ruler of the Mughal Empire (1526 – 1857). He respected a woman’s willingness to follow her husband to the afterlife but opposed self-immolation, feeling it was an inappropriate way to demonstrate loyalty. In 1582, Akbar issued an edict prohibiting Sati.

Although Akbar banned Sati, he did not go so far as to enforce the law strictly. It wasn’t until 1663, under Emperor Aurangzeb (1618 – 1707), that Sati was genuinely outlawed. In the eyes of colonial powers in India, Sati was also seen as a barbaric practice, and they attempted to eradicate it.

In 1798, the British imposed a ban, but it was effective only in the Calcutta area. In the early 19th century, in their efforts to convert Indians, they launched several campaigns against Sati, which ironically led to an increase in the number of cases. Between 1815 and 1818, the incidents of Sati doubled as Hindus abused the practice to express opposition to conversion.

In 1828, newly appointed Governor of India, Lord William Bentinck (1774 – 1839), firmly enforced the ban on Sati, imposing imprisonment on individuals and groups that practiced it. Although instances of Sati decreased, the practice did not vanish entirely and continued to be overlooked in many regions. It wasn’t until 1861 that the law against Sati was effectively implemented across India.

In 1947, India regained independence. Since then, both the government and the public have opposed Sati, yet in 1987, an 18-year-old widow named Roop Kanwar from Deorala village was coerced into Sati with her 24-year-old husband.

Thousands gathered to witness and praise the act, igniting a wave of anger across India. The Indian government had to issue preventive decrees against Sati, quickly passing new legislation that imposed severe penalties, including life imprisonment and the death penalty.

Despite the laws and awareness campaigns, Sati still has roots in a corner of Indian spirituality. Occasionally, it is performed, and as long as there is no investigation revealing coercion, the law cannot be enforced.

In the 17th century, a French traveler named Jean Baptiste Tavernier visited India and recounted seeing small huts constructed, in which the husband’s body was carried, and the widow was led inside, where the door was shut before the pyre was lit. Other travelers reported observing pits filled with combustible materials where the husband’s body was placed, and the widow was lowered in before igniting the fire. Both the hut and the pit served to prevent the widow from escaping and interrupting the Sati ritual. Moreover, widows were also permitted to consume poison, be bitten by venomous snakes, or commit suicide by knife beforehand.