Scientists have uncovered the secret of the “self-healing” wall surrounding the nearly 2,100-year-old tomb of the noblewoman Caecilia Metella.

The Tomb of Noblewoman Caecilia Metella was built in the 1st century BC along the Via Appia in Rome, Italy. The circular tomb stands 21 meters high and has a diameter of 29 meters, constructed from stacked concrete blocks and adorned with marble reliefs. It is one of the best-preserved monuments along the Via Appia and is among the most visited sites in Italy, contributing significantly to the country’s tourism revenue.

Inside the tomb of Caecilia Metella (CC BY-SA 3.0).

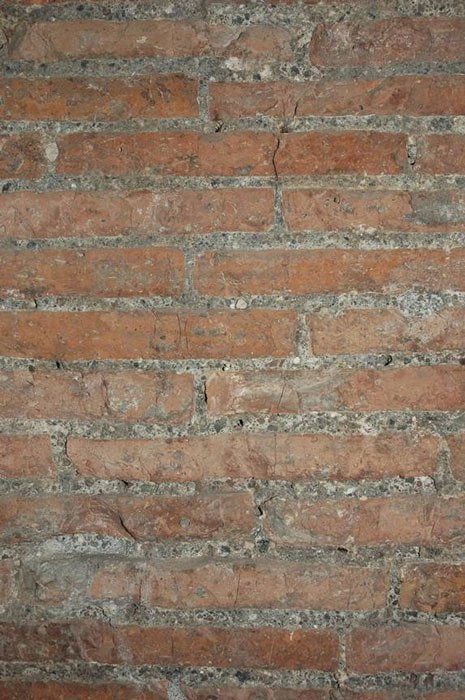

Volcanic rock is one of the building materials for the tomb of noblewoman Caecilia Metella (University of Utah)

The Caecilia Metella Tomb Complex is famous not only for its grand architecture and the power of the noblewoman but also for the remarkably intact structure of the protective wall surrounding the tomb, which has withstood the ravages of time. With support from the U.S. Department of Energy, geographer Marie Jackson (from the University of Utah) collaborated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to conduct an in-depth study of the materials and construction methods used in the Caecilia Metella tomb.

The tomb complex of noblewoman Caecilia Metella.

Ancient Romans used volcanic rock to create the rough brick walls, a material that has not deteriorated significantly over more than 3,000 years. The volcanic blocks were bonded together using a special mortar invented by the ancient Romans, made from hydrated lime and volcanic tephra (glass and porous crystals produced during volcanic eruptions).

The self-repairing sturdy wall of the ancient tomb (University of Utah).

This mortar contains a significant amount of leucite, which, when exposed to water, dissolves and releases potassium, further strengthening the wall. This is the answer to the mysterious “self-healing” property of the wall surrounding the ancient tomb.

Many structures need to be built underwater, concrete pipes going out to sea (Adobe Stock).

The U.S. Department of Energy has further funded this research so that scientists can create a version of concrete and mortar that consumes less energy and lasts longer when installed in marine or underwater environments. This research will be based on the manufacturing methods of ancient Romans.