The large pits, ranging from a few meters to 60 meters, scattered across the seabed off the coast of Germany were initially thought to be formed by methane gas. However, they were actually created by harbor porpoises.

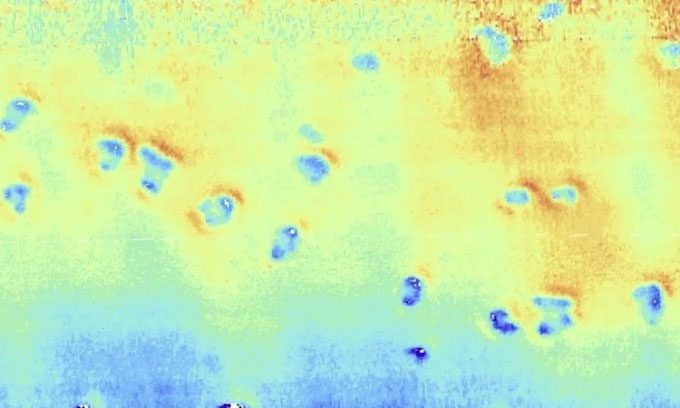

Under the murky waters of the North Sea, shallow pits are scattered across the ocean floor. These pits are circular or oval-shaped, with widths ranging from a few meters to over 60 meters, but they are only 11 meters deep. Some pits even merge together, creating depression areas resembling collective diagrams. Such shallow pits typically form when fluids containing methane or other groundwater rise from sediment layers. However, a study published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment indicates that thousands, even millions, of pits in the North Sea may be the result of harbor porpoises foraging for food. The research findings suggest that harbor porpoises and many other animals could play a significant role in shaping the seabed, as reported by Live Science on February 27.

Shallow pits on the seabed of the North Sea were initially thought to be caused by leaking methane. (Photo: Jens Schneider von Deimling).

For many years, geologist Jens Schneider von Deimling from Kiel University was skeptical about whether the shallow pits in the North Sea were caused by leaking methane. The seabed of the North Sea is composed of porous sand and experiences strong ocean currents, making it unsuitable for methane to accumulate in the sediment layers. Mapping studies conducted using echo sounders found no evidence of methane.

To better understand these mysterious shallow pits, the research team used multi-beam echo sounders, which allowed them to survey the seabed at high resolution. This new tool enabled researchers to examine the shape of the pits in detail down to the centimeter level. The multi-beam echo sounder revealed that, in fact, the shallow pits do not have a conical shape as would be expected if methane were released through the sediment layers, according to Schneider von Deimling. Regardless of their width, the pits are all about 11 centimeters deep.

When searching for the cause of the shallow pits, Schneider von Deimling consulted a friend who is a biologist and diver. This led him to discover that the harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) often rummages through the seabed to sniff out eel. Following this call, Schneider von Deimling collaborated with biologists studying harbor porpoises.

The research team used existing models to predict the habitat of harbor porpoises and eels, along with data on ocean currents. Both harbor porpoises and eels thrive in areas with strong currents. Researchers found that their habitats overlapped with the study area. Wherever they predicted harbor porpoises and eels would be found, they discovered more pits. The larger pits were created by harbor porpoises and were eroded by ocean currents.

Currently, the research team is working with scientists in Ireland to confirm their predictions about the locations of the pits based on the habitat of harbor porpoises in the North Sea. This interdisciplinary research could help biologists learn more about animal behavior. Understanding how shallow pits on the seabed form is crucial for assessing underwater risks. Pits created by leaking methane could signal a threat from tectonic activity. If scientists can identify pits created by living organisms, they may alleviate concerns about tectonic activity.