The origin of endothermy in mammals is one of the great unresolved mysteries of paleontology.

In the animal kingdom, only mammals and birds possess the ability to generate and regulate their body temperature. This process is known as endothermy or warm-bloodedness. It is one of the reasons mammals dominate nearly every global ecosystem. Warm-blooded animals are active both day and night and reproduce faster than cold-blooded species.

An artistic representation of Tritylodon, an extinct vertebrate from the order Therapsida, which was a nocturnal warm-blooded species, exhibiting characteristics such as water vapor emission from its lungs. (Illustration: Luzia Soares)

However, to date, it is still unclear exactly when the ancestors of mammals became warm-blooded. Recently, scientists employed cutting-edge technology to study fossils from the Karoo region of South Africa to find the answer: the development of thermogenesis in the ancestors of mammals occurred approximately 233 million years ago during the Late Triassic period (252 to 201 million years ago).

The origin of endothermy in mammals remains one of the great unresolved mysteries of paleontology. Scientists have attempted various explanations but often arrive at unsatisfactory conclusions. This research method is highly reliable as it has been validated through numerous specimens of modern animals, indicating that endothermy evolved at a time when mammals exhibited many other significant characteristics.

Warm-bloodedness is a key feature that defines mammals as we know them today. Endothermy can be seen as a starting point in the evolutionary process of mammals: it leads to the development of insulating fur, larger brain sizes, warmer blood circulation, faster reproduction rates, and a more active lifestyle. All these traits arise from warm-bloodedness.

So far, most scientists have assessed the transition to self-generated body heat as a gradual process over tens of millions of years, beginning close to the extinction event of the Triassic period. Meanwhile, some opinions suggest it occurred closer to the emergence of mammals, around 200 million years ago.

However, this new study suggests that endothermy appeared in the ancestors of mammals approximately 33 million years before mammals themselves emerged. This timeline aligns with recent findings indicating that many characteristics of mammals, such as whiskers and fur, also appeared earlier than previously thought.

This research stemmed from scientists’ investigations into the inner ear. The inner ear is not only an auditory organ but also contains the structures that control balance, namely the semicircular canals. These three canals are oriented in three spatial dimensions. They are filled with fluid that moves within the canals whenever the head moves, activating receptors that inform the brain of the precise three-dimensional position of the head and body. The viscosity of this fluid (endolymph) is crucial for the balance system to accurately detect the rotational movement of the head and aid in maintaining equilibrium.

Just like butter taken from the fridge melts when placed in a hot pan, or honey becomes thicker in cold weather, the viscosity of endolymph changes with body temperature. This means that when body temperature rises, the viscosity of endolymph also changes. In response to this change, the body must also adapt. In mammals, the semicircular canals adapt by altering their shapes.

Researchers observed the shape changes of these canals through fossil specimens. They believe that if they can identify species exhibiting these changes, they can accurately pinpoint the evolutionary moment of endothermy. From the rich fossil record in the Karoo, South Africa, they have reached compelling conclusions.

The Karoo region provides excellent preservation conditions for a treasure trove of fossils, including those of mammalian ancestors. These fossils serve as an uninterrupted record of life’s evolution over approximately 100 million years, documenting the transition from reptiles to mammals in incredible detail.

Using 3D CT scanning technology, researchers reconstructed the inner ear anatomy of dozens of mammalian ancestors from the Karoo and other parts of the world. They discovered which species had inner ear structures compatible with warmer body temperatures and which did not possess that trait.

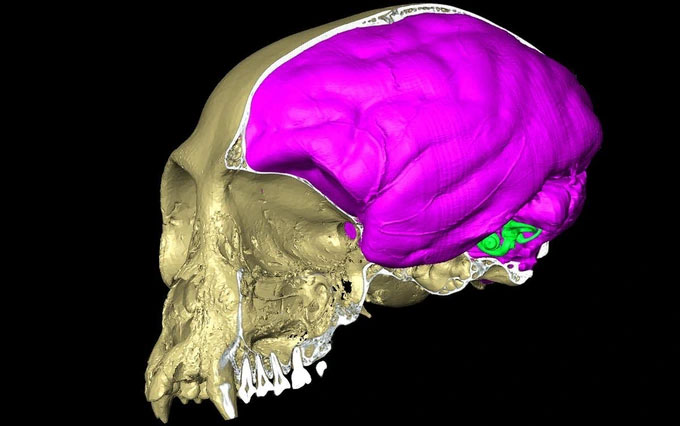

The brain (in pink) and inner ear (in blue) of a primate – a modern mammal, illustrated by Julien Benoit.

It is important to note the geographical location of the Karoo region at the time these animals lived. During that period, this land was closer to Antarctica than it is today due to continental drift. This means that the warmer body temperatures (evidenced by the shape changes in the inner ear) were not due to a warmer climate. Given that the average climate in South Africa at that time was cooler, the changes in endolymph viscosity in the inner ear could only be attributed to the evolved and warmer body temperature of mammalian ancestors.

Until now, scientists have only been able to rely on skeletal features to reconstruct the evolution of endothermy, leading to inaccurate research results. With the discoveries from the study of the inner ear, they believe this could be the key to unlocking a wealth of knowledge about the ancestors of mammals.