It was once believed that the DNA of ancient Egyptian mummies could not be sequenced. However, an international team of researchers, employing unique methods, has overcome this barrier to achieve that goal.

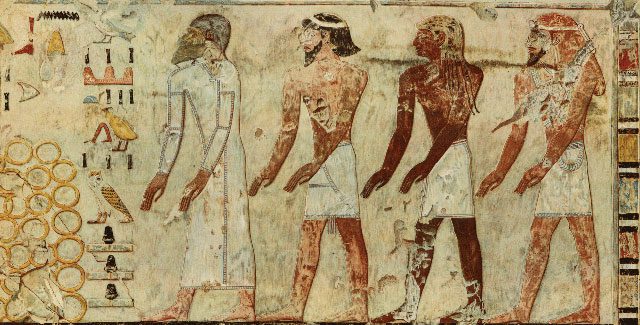

Egyptologists, writers, scholars, and others have debated the ethnicity of ancient Egyptians since at least the 1970s. Today, some believe they were sub-Saharan Africans, a claim supported by the existence of several African empires and kingdoms that thrived in the past.

It was commonly thought that the issue was that the DNA of mummies could not be sequenced. But a group of international researchers, using innovative techniques, has surpassed inherent obstacles to accomplish this. They discovered that ancient Egyptians are most closely related to populations in the Near East, particularly from the Levant – the eastern Mediterranean today, which includes the countries of Turkey, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. The mummies used in the study date back to the New Kingdom and later periods when Egypt was under Roman rule.

Some believe that ancient Egyptians were sub-Saharan Africans.

Modern Egyptians share 8% of their genes with Central Africans, significantly more than ancient Egyptians, according to research published in Nature Communications. The increase in sub-Saharan genes has only occurred in the last 1,500 years. This may be due to trans-Saharan slave trade or from long-distance trade, which frequently occurred between the two regions. The researchers assert that improved travel along the Nile during this period enhanced trade between ancient Egypt and inland Africa.

Throughout ancient history, Egypt has been conquered multiple times, including by Alexander the Great, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and more. Researchers wanted to determine whether these continuous waves of invasion caused any significant genetic changes in the population over time.

The increase in sub-Saharan genes has only occurred in the last 1,500 years.

Team leader Wolfgang Haak at the Max Planck Institute in Germany stated in a press release: “The genetics of the Abusir el-Meleq community did not undergo any significant changes over the 1,300 years we studied, indicating that the population remained relatively genetically stable and was not significantly affected by foreign conquest and rule.”

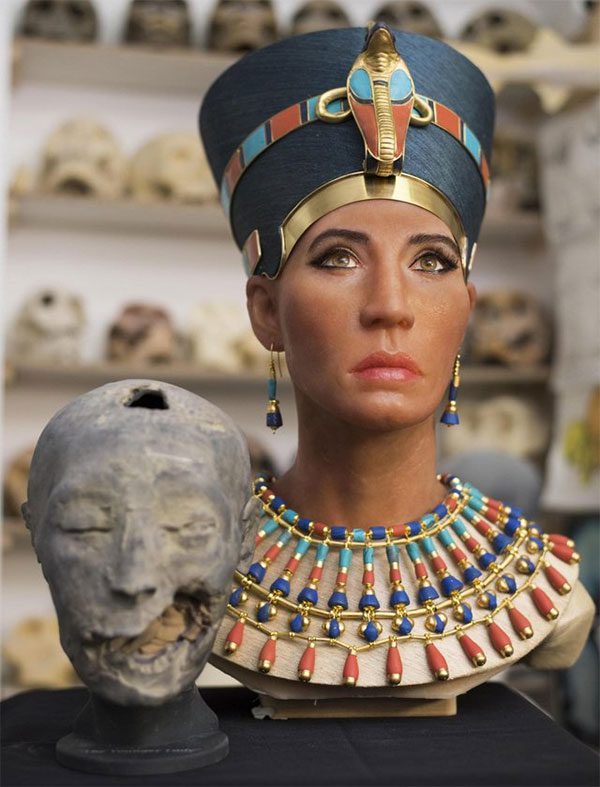

The study was led by paleogeneticist Johannes Krause, also from the Max Planck Institute. Historically, there has been a challenge in retrieving intact DNA from ancient Egyptian mummies. The study notes: “Egypt’s hot climate, high humidity in many tombs, and certain chemicals used in embalming techniques contribute to DNA degradation and are believed to be the reason why DNA in Egyptian mummies does not last long.”

It is also believed that even if genetic material is recovered, it may not be reliable. Nevertheless, Krause and colleagues were able to introduce robust DNA verification and sequencing techniques, completing the first genetic analysis of ancient Egyptian mummies.

Scientists have completed the first genetic analysis of ancient Egyptian mummies.

Abusir el-Meleq, an archaeological site along the Nile, is located 70 miles (115 km) south of Cairo and features mummies that showcase aspects of devotion to the worship of Osiris, the green-skinned god of the afterlife.

Initially, mitochondrial DNA from 90 mummies was sampled and analyzed. From these, Krause and colleagues found that they could obtain the complete genome from just three of the mummies. For this study, the scientists sampled teeth, bones, and soft tissues. Teeth and bones provided the most DNA as they were protected by soft tissues during the embalming process.

They began their work by sterilizing the room. Then, they placed the samples under UV radiation for an hour to disinfect them. From there, DNA sequencing could be performed.

The scientists also gathered data on Egyptian history and archaeological data from northern Africa to provide context for their findings. They wanted to understand the changes that occurred over time. To do this, they compared the genomes of the mummies with the genomes of 100 modern Egyptians and 125 Ethiopians.

The ability to collect genetic data from ancient Egyptians is a significant achievement.

The oldest mummy identified dates back to the New Kingdom, around 1,388 BC, when Egypt was at the height of its power and glory. The youngest is from AD 426, when the country was ruled from Rome. The ability to collect genetic data from ancient Egyptians marks a significant achievement, opening new research directions.

The scientific report also points out: “All our genetic data were obtained from a single site in Central Egypt and may not represent all of ancient Egypt.” “In southern Egypt, the genetic makeup of the people there may have differed, resembling more closely that of the interior of Africa.”

Future researchers aim to determine precisely when sub-Saharan African genes entered the gene pool of ancient Egyptians and why. They will also want to know where ancient Egyptians originated. To do this, they will need to identify older DNA, as Krause stated, “going back further in time, into prehistory.”

Using high-throughput DNA sequencing validation techniques and advanced verification methods, researchers have demonstrated that they can extract reliable DNA from mummies, despite the harsh climate and the embalming techniques that may damage DNA.

Further testing could contribute significantly to our understanding of ancient Egyptians and perhaps even those from other regions, helping to fill gaps in the collective memory of humanity.