What mystery lies behind the monotonous voice announcing repeating place names, characters, and numbers without any apparent pattern on shortwave frequencies?

There are two groups of people who frequently listen to the radio. Most are ordinary individuals around us who regularly tune into FM/AM or internet radio. The other group is a small number of “wave hunters” on high frequencies (also known as shortwave), alongside very high and ultra-high frequencies, which are used by communication devices within the security sector and even satellite signals.

Shortwave enthusiasts often pick up signals transmitted at extremely high frequencies from international radio stations broadcasting from China, Cuba, Iran, or Romania, or from maritime and aviation communications.

The energy of shortwave radio frequencies can reach any location on Earth because it is influenced by the reflection of the ionosphere. Therefore, shortwave signals can travel very far, transcontinental, unlike local radio stations.

However, alongside typical news and entertainment broadcasts, sometimes these wave hunters catch signals from mysterious channels, with a monotonous voice reading numbers, characters, or place names in a seemingly random manner. Sometimes these are read live, sometimes in Morse code, and sometimes through digital noise. Collectively, these are known as number stations.

Examples of some number stations that YouTubers have “hunted”:

Number stations have existed since World War I. Over the years, they have attracted attention from journalists, video game developers, and filmmakers. Despite this interest, very few explanations have been provided about them. They are often described as “haunting,” “creepy,” or “mysterious”, and discussions tend to end there.

This might disappoint some, but these number stations are not signals from extraterrestrials or mind control devices, nor are they remnants from the Cold War – rather, they are part of the complex communication methods used by intelligence agencies and the military.

The Significance of Number Stations

Cryptography, the science of encrypting text and data, has existed since the time of Caesar. Before the invention of radio, secret messages could be transmitted using coded letters or through light signals. Radio emerged in the early 20th century and quickly found military applications. A prominent example was when Germany intercepted radio command transmissions from the Tsarist Army, helping it achieve significant victories in East Prussia in 1914.

The use of number stations was first discovered in the later years of World War I when they were sent in Morse code at low and medium frequencies. Shortwave began to be used in the early 1920s to send encrypted messages. When directed at the ionosphere at an angle, shortwave signals reflect back to Earth at very long distances beyond the horizon. This was very convenient for overseas intelligence operations or for military command to send orders to distant units.

However, if these signals can be heard worldwide, even by civilians, then the messages must be encrypted. That is why we have the One-Time Pad (OTP) system.

OTP is considered the only mathematically unbreakable encryption system, typically a sheet of paper containing random numbers grouped in sets of five digits or more. To decode OTP, two unique copies of the message are needed, one held by the sender and one by the receiver. Typically, these are very small to conceal easily or made from combustible material for quick destruction after use.

The encoding and decoding method of OTP is extremely simple but unbreakable because it is entirely arbitrary. Here, only the simplest method is presented, but more advanced methods have similar mechanisms.

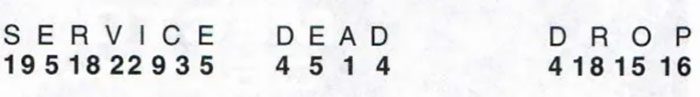

First, the letters of the alphabet are assigned a specific number, for instance, A is 01, B is 02, C is 03… and so on for the entire alphabet.

In step one, the sender writes down the message along with the corresponding numbers in rows.

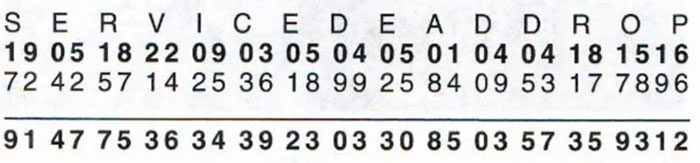

In step two, using completely random numbers from the first copy of the OTP, they add these to the numbers in the row above. For example, the OTP has the numbers 72, 42, 57, 14… as shown below.

The result is a new sequence of completely random numbers (94, 47, 75…). If the result exceeds 100, only the last two digits are taken. This sequence is then grouped into fives and sent via the number station: 91477 53634 39230…

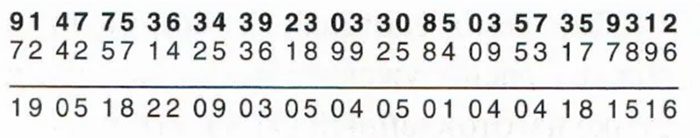

To decode, the receiver uses the second copy of the OTP with numbers matching the first copy. Instead of adding as in the encoding process, they will subtract to get the result.

From this result, they convert it back to letters as per the original agreement of the organization. For example, 19 is S in the alphabet, 05 is E,… and so forth to decode each letter back to the original message.

For OTP to be unbreakable, a prerequisite is that the OTP sequence must be as long as the encoded message, consisting of completely random numbers, never reused, and only two copies exist.

This process is simple but highly effective: A third party can only decode the message if they can access the receiver’s OTP. This sometimes happens through counterintelligence operations, using double agents, or by capturing the receiver, especially when they are receiving the signal. Several events in the 20th century have demonstrated that intelligence agencies have indeed used these signals.

From 1945 to 1956, the CIA and British SIS dispatched agents to support guerrilla forces against the Soviets in the Baltic states, Belarus, and Ukraine. Most were captured along with radio transmitters and books containing numerous OTP pages. The KGB used these codes to force captured agents to send false information back to headquarters. In 1988, the KGB featured these codebooks and transmitters in a TV show titled “The Game.”

In 1983, the KGB uncovered CIA agent Alexander Ogorodnik, a Soviet diplomat receiving instructions from American radio stations. Another famous case was the “Cuban Five” in 2001, where Cuban agents were arrested in the U.S., and shortwave broadcasts were used as evidence against them. Messages consisting of numbers were sent to agents via radio and entered into a Toshiba laptop.

It was later decoded using a special diskette containing the decryption key. In 2013, a German couple was tried for spying for Russia and revealing military secrets. They had also received messages from shortwave and were caught while receiving them.

Number Stations Today

The most active number stations began around 1960, with channels like The Lincolnshire Poacher, The Swiss Rhapsody, and Gongs being broadcasted. Activity significantly declined after the collapse of the Soviet Union, as many intelligence agencies used number stations linked to the KGB, such as Stasi and the Romanian Security Agency.

In turn, many Western intelligence agencies began to use new means of sending encrypted messages such as steganography, which involves encoding messages within images or any digital medium. However, monitoring groups have indicated that Russia’s foreign intelligence agency, SVR, still widely uses this method.

Other countries that utilize number stations may include North Korea. From 2000 to 2016, North Korea continued to broadcast encrypted messages directly from the state-run radio – Pyongyang Radio – disguised as problems or physics questions for “distant university students.”

Not all number stations are transmitted in the native language, and some may use foreign languages. It is also worth noting that military uses them for purposes beyond intelligence. For instance, Russia’s famous “Buzzer” station has been used internally by the Russian military to send tasks and orders to various military units within the country. This is partly evidenced by their stations transmitting signals during the day, and due to the ionosphere’s activity at this time, the messages do not transmit well to Western Europe and the U.S.

It is very easy to listen to these stations. You do not necessarily need a shortwave radio; most stations today are identified by software and can be listened to remotely via the internet. Since these receivers are operated by software, people worldwide can connect online and operate them remotely, not to mention that the community of “number station hunters” also exists and actively operates on the Internet.