In the early stages of the Solar System, everything operated much more violently than today. The remnants of that era still linger on rocky planets.

This period is described by scientists as rife with violence. Rocks flew uncontrollably through space, colliding with newly formed planets, creating impact craters and even deepening existing ones.

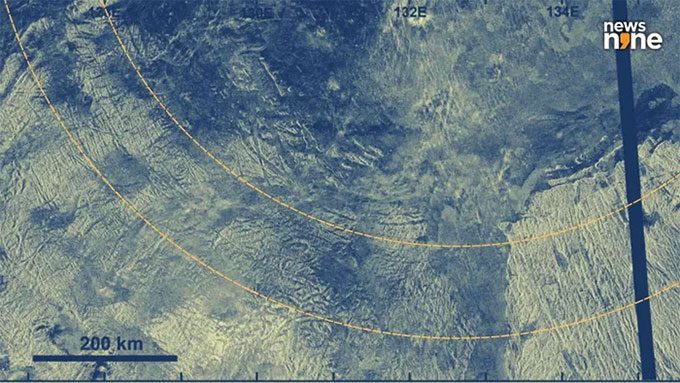

Strange patterns on the surface of Venus intrigue scientists.

Mercury, Mars, and the Moon were all ravaged and bear heavy scars. Even Earth—where geological processes and weathering have quickly eroded most evidence—shows signs of major impacts.

However, there is something truly peculiar about Venus. Despite this hellish planet having perfectly preserved impact craters on its surface, scientists have been unable to find evidence of impact scars larger than 300 km in diameter, known as impact basins.

Now, that evidence has emerged. However, it is not what we had speculated. Instead, this could provide us with new insights into the formation and evolution of Venus when the Solar System was still young.

The evidence is a feature known as tessera terrain; a series of concentric rings on the surface of Venus that measure about 1,500 km in diameter. New analysis shows that the Haastte-Baad Tessera impact basin on Venus resulted from two massive collisions approximately 3.5 billion years ago, one occurring right after the other, similar to a new bomb hitting an old bomb crater. At that time, Venus was a planet still soft and molten beneath its thin crust.

Geologist Vicki Hansen from the Planetary Science Institute stated: “If this is indeed an impact structure, it would be the oldest and largest structure on Venus, giving us a rare glimpse into the planet’s past and providing information about the early processes of our neighbor.”

“Perhaps more importantly, it shows us that not all impact structures are alike. Impact structures result from a meteoroid—an object with an undefined composition—colliding with a target planet. The composition of the meteoroid is crucial, but the nature of the target, which in this case is Venus, is just as significant.”

As rocky planets formed, their interiors were much warmer than they are today. Their molten interiors also occupied a larger volume beneath a much thinner crust. Hansen and her colleagues conducted modeling analysis to study the formation processes that could create the Haastte-Baad Tessera impact basin and determined that the dual impacts are the most plausible scenario.

Two objects colliding with Venus in succession would penetrate the thin 10 km crust of the planet and blast into the molten mantle below. Magma would bubble up to the surface and the surrounding area would crumple, forming the concentric tessera patterns.

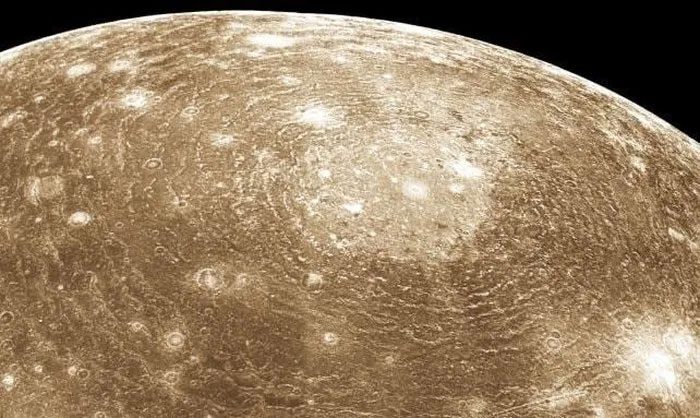

The surface of Callisto’s moon still shows the impact scar of Valhalla with concentric tessera patterns.

We know that this process can occur because we have observed it elsewhere in the Solar System. On Callisto, one of Jupiter’s moons, there exists a multi-ring structure about 3,800 km wide. This is known as Valhalla, the largest known multi-ring impact structure in the system, and scientists believe it was formed when a large object struck Jupiter’s icy moon. Cold water rose from below to fill the void, and the impact deformed the surrounding crust.

A puzzling issue with this model is that it is sometimes found on a plateau. This does not apply to the Haastte-Baad impact basin, but it does raise questions about tessera terrains found on other plateaus on Venus. If an impact cannot create tessera plateaus, there must be another force driving the formation of these concentric structures.

Geologist Hansen explains: “When you have a large amount of partially molten material in the mantle rising to the surface, the remaining material is called residue. The solid residue is much more heat-resistant than the adjacent layer, so part of the mantle remains unmelted. Surprisingly, the solid residue has a lower density than all the surrounding mantle layers. Therefore, it floats on the lava.”

Essentially, you have a gas cushion lying within the mantle below your lava pool, and it will rise, pushing up the tessera terrain. If the lava remains in place, it will solidify at that raised position. If it flows away, the elevation of the terrain will decrease, as we see with the Haastte-Baad impact basin.

Modeling shows that the impacts produce quite large terrains, approximately 75 km wide. This seems relatively rare in the Solar System, but it is not unprecedented; there are geological features on Earth that can form in the same way, such as a series of lava domes scattered in Lake Victoria in Africa.

Hansen states: “Who would have thought that flat or low tessera terrain or a large plateau is the shape of an impact basin on Venus? We have been searching for large impact basins on the ground, but for that to occur, you need a thick lithosphere, which early Venus did not have. Mars has a thick lithosphere. The Moon has a thick lithosphere (which is why craters remain intact). Earth may also have had a thin lithosphere when it was young, but the geological record has changed or disappeared significantly due to erosion and plate tectonics.”